The author remembers Stan Shaw as only she can

By Grace Horne

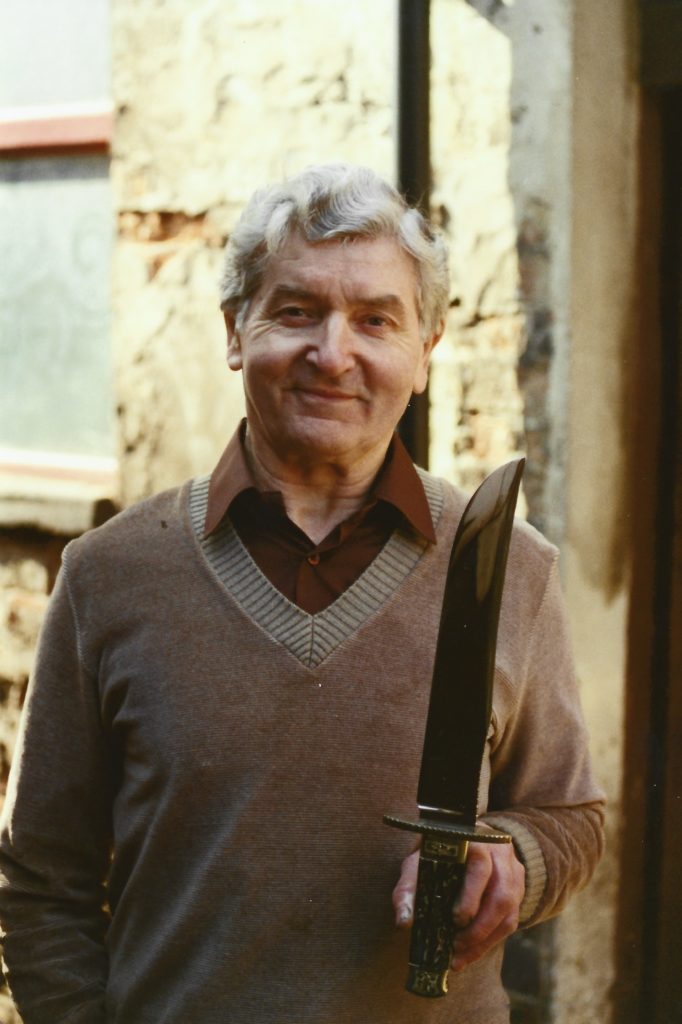

Sometime in the early 1990s, a journalist—to the chagrin of the handful of other knifemakers also still working in Sheffield, England—described Stan Shaw as “The Last Little Mester,” and the title stuck until Stan’s passing in February. Stan made many fancy pocketknives but “Little Mester” was never simply a title that denoted mastership of a craft skill.

Historically, workers in the Sheffield cutlery industry were notoriously independent. As the industry moved from craft-based to industrialization, nearly all cutlers were on piece-work and would rent space in the workshop—a yard of bench or a “trough” for grinding. Work came from other workers, and each worker did a very specific task on the knife before it was passed to the next worker. The process was efficient because of the hyper-specialization of all of the workers in the chain. There was a complicated, ever-changing network of subcontracting, renting, supplying and rivalries, but no one learned all the processes to make a knife—there was no concept of sole-authorship.

In her thesis, Sally-Ann Taylor* states that the “differing opinions regarding the status of the little mester reflected the actual diversity in his possible position and role. Some felt that the title implied that his enterprise should involve him in a certain number of commercial risks and liabilities. Sometimes he was an actual workman himself, obtaining orders from larger factors, merchant or manufacturers, and then employing a few men to help him … sometimes even these workers would employ others beneath them, but usually only members of their own family—particularly women and children.” Hence, little mesters were small-scale flexible employers, recruiting workers to supplement their own labor as required.

In 1844, a commentator on the cutlery trades stated that “there are several modes of conducting the manufacture, but the factory system is not one of them … there is no large building, under a central authority, in which a piece of steel goes in one door and comes out at another converted into knives, scissors and razors. Nearly all the items of cutlery made at Sheffield travel about the town several times before they are finished.”**

HE KNEW at 14

Stan didn’t come from a cutlery background. He was born in 1926 in a small village outside Sheffield, and, after seeing a market stall of knives, decided at 14 that that was what he wanted to do. By chance, he walked into the prestigious company, Ibberson, and spoke to the owner, Billy Ibberson.

Pointing to a showcase displaying the firm’s best pocketknives, Stan said he’d like to learn how to make such knives. As Stan recalled, “Billy then fetched up one of the cutlers, Ted Osbourne—a little bloke about 5 feet or so tall—and asked, ‘Will you have him?” He said, ‘Yes.’ And I started on the Monday at an apprentice’s wage of 10 shillings a week.”

When Stan joined the firm, the old patterns of working had long gone; “little mesters” and “factors” had morphed into the more familiar patterns of factory working, with all the workers employed by the company and paid a wage. He was one of the last apprentices to be taken on and his curiosity about the entire process of making folding pocketknives was insatiable. As he moved through Ibberson and other companies over the years, he actively approached other workers to learn their processes as well as his own. It was this breadth of training that made him unique and was vital to him in later life.

THEIR PATHS CROSS

By the beginning of the 1980s, the contraction of the Sheffield cutlery industry was such that there were no more companies left to employ him, so he set-up his own workshop in Garden Street. It was there, 10 years later, that our paths crossed.

I had made a set of three folding knives for a college project and hadn’t been able to find anyone still making traditional Sheffield slip joints to ask for advice. A couple of years later, I heard Stan being interviewed on the radio and realized that I still desperately wanted to learn to make knives. I packed up my workshop in London and moved to Sheffield to persuade him, in person, to take me on as his apprentice. He welcomed me into his workshop but said that he was nearly 70 and too old for an apprentice. Instead, he offered me his bucket of old, handforged blades and springs, told me to select a handful and “go and figure it out yourself because it’s not that hard.” He would always be there to help if I got stuck.

A few years ago, when I was gently teasing him about still having a 10-year waiting list for his knives, he said, “I should have taken you on then, lass, you’d just about be useful to me now!” So, for all the times our paths crossed, for all the gentle encouragement and for completely changing my life’s path when I was 23 years old, thank you, Stan.

Stan was not a “little mester.” He was a master and was proud that he could make his knives from start to finish, a concept that would be completely alien to Sheffield knifemakers a hundred years ago.

Stan Shaw, whose career of making classic pocketknives spanned almost 80 years, passed in late February at the age of 94.

He started work for W.G. Ibberson in Sheffield, the old knifemaking capital of England, in 1941. Apprenticed to Fred and Ted Osborne, men Stan described as the two best cutlers in Sheffield, he eventually succeeded them in 1954 as the company’s top maker of pocketknives. Though the Sheffield knife industry was in rapid decline, he continued making knives, renting an old workshop in 1983 and becoming an independent cutler.

As an independent he did it all in the making of his pocketknives, and he did it all quite well. As he said in “Stan Shaw: Little Mester of Sheffield” in the May 1994 BLADE: “I have to do everything now because there are no forgers, grinders, scissor-makers and so on left. My earlier experience with Ibberson’s has proved invaluable in that respect. All my knives are hafted, ground and assembled by me. It’s harder work but the satisfaction is greater. Scissors, files, punches, shields, shackles, handles, scales, bolsters—the list is endless—but each part is made by me on these wheels and dollies with only hacksaws, files and a few other traditional tools, such as my parser. The only job I don’t do is the occasional engraving I have done on the bolsters.”

His knives are testaments to the classic exhibition pieces, many with a host of blades and other tools and implements. In 2003 he became an honorary freeman of the Company Cutlers and in 2017 was awarded the British Empire Medal. As late as 2019, into his 90s, he continued to clock in bright and early in the mornings to make pocketknives at Kelham Island Museum. In the interim he served as a mentor to many makers, including award-winner Grace Horne, among others.—by BLADE® staff

Editor’s note: An award-winning knifemaker from Sheffield, England, the author currently makes traditional folders. For more information contact her at Dept. BL9, The Old Public Convenience, 469 Fulwood Rd., Sheffield, United Kingdom, S10 30A [email protected], gracehorn.co.uk. Also: Steven and Kylie Cocker, Instagram @steven_cocker_sheffield; Michael May www.michaelmayknives.com; and/or Michael and Ashley Harrison plus apprentice at A Wrights & Sons www.penknives-and-scissors.co.uk.

*Tradition and Change: The Sheffield Cutlery Trades 1870-1914; Sally-Ann Taylor

**The Penny Magazine Supplement, April 1844, p.168; Thomas Allen

Read the full article here