This story, “Big Bucks of the Secret Canyon,” appeared in the December 1962 issue of Outdoor Life.

Never belittle the beneficial effects of square dancing. My brother Harold met a cattle rancher at a square dance in north-central Washington and got the guy’s permission to hunt in a canyon at the back of his place. This was a notable achievement, as the rancher didn’t hunt, didn’t like hunters, and had a locked gate across the cowpath road that led into the canyon.

All this seemed of no importance to me, as there are enough canyons in Washington for everyone, most of them with free access. Harold, however, developed a stubborn conviction that we would find something unusual on his friend’s place. He talked my son Dave and me into giving it a whirl.

We started out with our fingers crossed, intending to move camp and seek greener pastures in a hurry if big mule bucks didn’t swarm all over us. Harold was on vacation from his job as a supervisor in one of the big Boeing plants in Seattle. I had time off from my duties as editor of Boeing Magazine. Dave is a university student, not above playing hooky for a couple of days to go deer hunting.

The car was loaded like a prospector’s burro, and Harold wanted to know where we would put the bucks. I told him not to worry. The way Dave consumed groceries, most of our load would be gone in short order.

We started the six-hour drive from Seattle on a November day that was gray and cold as a banker in charge of small loans, but we didn’t hit snow until we got safely through the rancher’s gate, halfway across the state from home. The ranch road was a pair of snow-covered ruts wobbling through pine forest, bunch grass, and broken lava outcroppings. It led us into a canyon that wound darkly upward toward distant peaks. There was no sign of man or beast, except Hereford cattle that stared gloomily as we passed. We went through another gate. Beyond it there were no more cattle. The snow deepened and a rock smacked the bottom of the car with a heavy thud.

I don’t believe that a cow could have traveled parts of that road without scraping her drip pan. Dave and Harold got out and walked ahead, rolling rocks to one side and scouting the way. Once or twice we detoured through the woods for easier going. Occasionally we hit a smooth stretch and roared along at 10 miles an hour. Finally, about the middle of the afternoon, we picked a flat spot near a trickle of water that ran across the wheel ruts and wheezed to a stop.

Dave is about as handy around camp as a cub bear playing a piccolo, so we told him to go scout the hills while we put up the tent. He left at a lope, with five slices of bread in one hand and his remodeled Springfield .30/06 in the other. He has been hunting since he was 12 years old and has the instincts and some of the abilities of a wolf.

We made a good camp, shoveling away the snow and digging a hole in the creek bed deep enough to dip a bucket. We put up a tent and a lean-to facing each other about 10 feet apart and built a fireplace between. Air mattresses were blown up and sleeping bags rolled out. A gasoline stove and lantern, a folding table and canvas stools were set up. Presently we sat in great comfort beside a roaring fire of pine logs, while a potful of beef stew and green lima beans slowly thawed on the stove.

Darkness settled early in the canyon under the snow-threatening sky. We let the stew simmer a long time, thinking Dave would be along, but finally ate without him. About nine o’clock, with the night as black as the inside of a witch, we heard snow crunching. Dave came out of the woods demanding food.

He ate and talked. “Tracks all over the place,” he said, “but I never saw a deer. I went up that north-facing slope, and it’s rough. There are cliffs, rock slides, gullies, and thickets. Near the top, the snow is 10 inches deep. I went along the ridge toward the ranch about three miles, until it got dark. Then I headed for camp.”

Harold decided that Dave had chased all the deer off the north-facing slope onto the south-facing slope, which got more sunshine, was far more open, and not so steep.

I wasn’t so subtle. I decided to go up the south-facing slope also, but just because it was easier.

We rolled out of warm sleeping bags before dawn in a world as still and white and cold as the moon. The bucket had been half full of water; it was frozen solid to the bottom. I hit the ground with the butt of the ax and it rang like iron. But the sky glittered with stars. We’d see the sun this day. Dishes were left in an untidy mess for the first man who came back to camp. Dave headed up his dark and jagged slope, this time angling away from the ranch instead of toward it. Harold and I were slower getting organized. Snow at the top of the south-facing slope was rose color in the dawn as we left our shadowy camp. Harold angled to the west; I went eastward and skyward.

I was carrying for the first time on a hunt my newest pride and joy, a 6.5 mm. Swedish Mauser that I’d whittled and polished all summer. An ad in OUTDOOR LIFE by a Chicago mail-order firm described the little rifle in such glowing terms that I wrote a check and mailed it. The rifle was shipped promptly. Mechanically, it was like new, with a polished steel bolt, an action as slick as grease, and a barrel that looked as if it never had been fired. The birch stock was dented and discolored. I fixed that by cutting part of it off, sanding and oiling the rest until it was the color of honey and smooth as glass.

A Redfield rear peep and a fine front bead were installed by a gunsmith. The whole outfit weighed a little more than seven pounds and felt like a feather after the relatively heavy .30/06 I was used to. I fired a couple of boxes of shells sighting in and just shooting, and made some fair groups in the black at 100 yards. For hunting, I was using 139-grain soft-point bullets loaded by Norma of Sweden, which were supposed to give 2,580 feet per second at the muzzle of the 18-inch barrel. It sounded like good medicine for the close or medium-range shooting I ordinarily get on deer hunts.

Fifteen minutes out of camp I stepped around a rock outcrop and saw two deer on the slope ahead. They took off in stiff-legged bounds toward a brushy gully. One of them was a forkhorn — not the big buck I’d have liked, but a fine piece of venison if I could get him to lie down.

The little Swede jumped up as if it were alive, but I had trouble seeing clearly in the dim light. The deer were about 150 yards away, jumping like kangaroos. I shot three times before they went out of sight. After clawing up the hill, I followed the tracks half a mile before losing them in a maze of other cloven prints.

I paused to consider, also to get my breath. I squinted through the sights again. Then I did what I should have done in the first place: screwed out the small-aperture disk in the peep sight and threw it into the brush. With that out of the way, I could see about four times better and center the bead just as well.

I followed the deer trail, angling uphill. Half an hour later, seven muleys trotted out of a gully ahead of me and stood on a snowy slope while I glassed them thoroughly. There wasn’t an antler in the bunch.

The sun was striking through the trees, mostly scattered pines, with firs in more dense growth on better-shaded hillsides. In places, the slopes were bare except for bunch grass and thin snow. By noontime it was warmer and the snow was melting. I sat down on a silvered log to eat a sandwich.

Across the canyon and westward, Dave’s Springfield started hammering. I counted four shots and at first was willing to bet he’d be back in camp early and would have to do the dishes. Then I had doubts. He might have thought the same thing of me when I shot three times and missed.

There were tracks everywhere, and I kept seeing deer, but all that I got a good look at were does. I went nearly to the top of the ridge and prowled along it, crossing some deep, brushy gullies, searching through patches of woods, having a fine time. Except for our party, there wasn’t another hunter for many a mile.

Darkness fell when I was high on the ridge above camp. I came down a cattle trail with the red campfire showing off and on through the trees. I had seen 14 deer, including one small buck. Harold had seen 12 deer, all does.

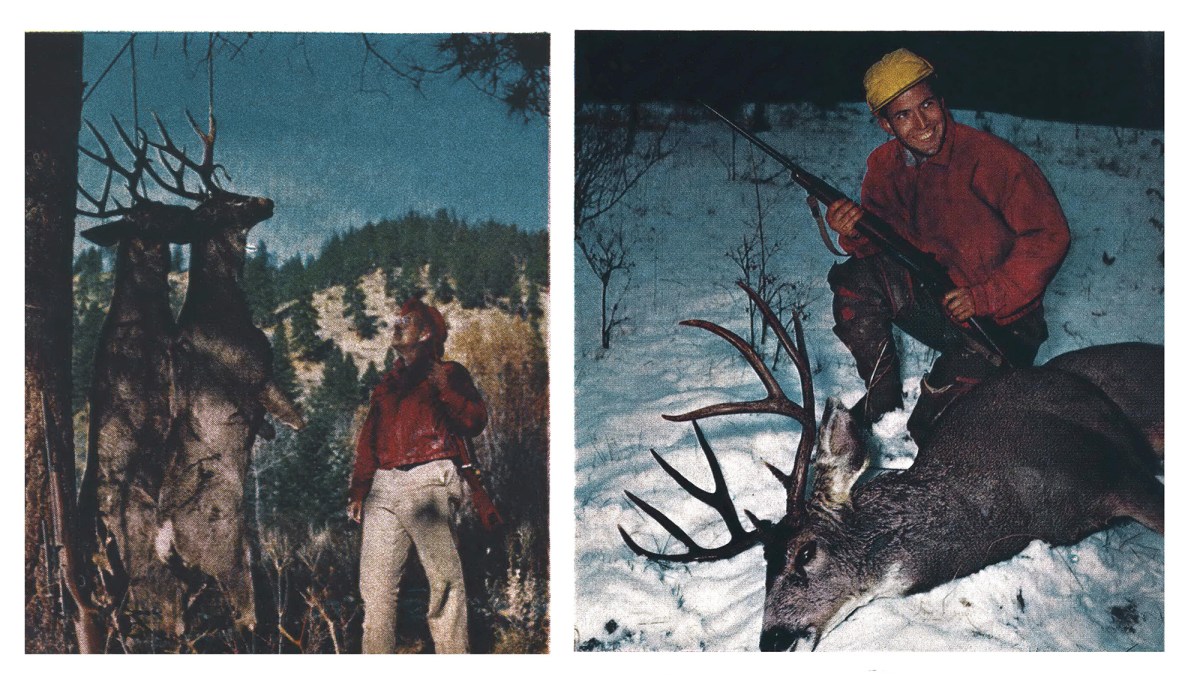

Dave was grinning like a monkey sucking eggs. He had a heart and liver in a pail and declared that if we old fogies would get out of the cow pastures and up in the cliffs and thickets, we’d have to rattle stones in tin cans to keep the big bucks from stepping on us. There were so many, he said, and they were so big that they scared him.

“Was that why you waited until noon to shoot one?” Harold asked thoughtfully.

Dave said that every time he got ready to shoot a buck, a bigger one would show up on the next hogback and he would take out after it. He was worn out, he said, from running down one gully and up the next.

Harold said, “I still think I’ll hunt the south-facing slope tomorrow.”

When dawn came again, as clear and wonderful as the seventh day of creation, Dave stayed in the sack. We kicked him a few times, but it did no good.

“If I never see a buck,” said Harold, lifting his coat tail to warm his rear at the fire, “I’ll still like this place. No people — that’s what I like about it.”

I poked five cartridges into the little Swede, closed the bolt, and squinted at the dark and forbidding thickets of Dave’s north-facing slope. Shots would be close in that kind of cover, suitable for a fast-handling, iron-sighted rifle. And the crag rock below the rim was buck country if I’d ever seen any. I decided to try it, rough going or not.

It was not only rough and steep, but also slick. Deer tracks laced the snow. I followed the trails, walking three or four careful steps and standing still for a second or two, scanning everything I could see. Many of the trees on this shady side were firs, growing close together. Brush was plentiful, offering feed for 100 deer.

I spent two hours zigzagging up the hill to cliffs and rock slides below the crest. Snow was deeper than my boots, and I was wet to the knees. The sun, yellow in the blue sky, worked hard at warming and melting. A series of hogbacks and deep, rocky gullies ran up and down the hill, offering the best kind of hunting.

By walking parallel to the ridgetop, going down into each gully and over each hogback, I had a perfect chance to surprise game and get a fair crack at it as it fled up the opposite slope. Anyway, that was my theory.

It wasn’t easy. Some of the gullies were a quarter of a mile across and 500 feet deep. I edged around cliffs and inched across rock slides. Mostly I traveled on deeply worn deer trails. I never saw so many tracks without hair nor hide.

At the bottom of one gully, I found footprints and a rut in the snow marked with bits of gray hair and bloodstains. Evidently Dave had pulled his buck downhill a good distance before hanging it up for the night.

I sat down on the next hogback and ate a sandwich. Ahead lay an infinite number of other hogbacks with gullies between. The ridge and canyon twisted back and up. Beyond were more big canyons and more big ridges with white peaks jutting into the sky. In the far distance was the great backbone of the Cascades, where snow in the glaciers was 100 feet deep and wouldn’t melt for 1,000 years. Somewhere between here and there, I thought, there must be at least one buck.

I crept over each hogback and peered into each gully with more breathless anticipation than a person with good sense. In the second gully beyond the one Dave had bloodied, it paid off. When my head came over the rim, I looked squarely into the startled eye of a big doe. She jumped out of sight as I topped the hill.

A couple of other does were thumping down the slope. More deer began jumping. There must have been 15 or 20 here and there in a dozen acres of timber, brush, and hillside broken with small cliffs. Instead of going to the bottom of the gully and up the other side where I could have seen them well, the contrary beasts plunged down the ridge, screened by rocks and trees.

I caught a glimpse of one set of antlers, then another, and another. The herd held at least three bucks with big, spreading racks. One buck was heading for an opening. The little Swede snuggled into my shoulder as if it belonged there, and this time I had no trouble looking through the open ring of the rear sight.

When the buck came into the clear, the bead was on him, the range about 75 yards. He never faltered at the rifle’s crack, but made two or three more prodigious bounds, on into the timber, while I furiously bolted in another shell. Then through the trees I saw an explosion of snow and four hoofs making an upside-down arc through the air.

When I found him, he was dead, shot through the heart. I didn’t know which tickled me the most, the little Swede’s performance or the big rack of antlers. I looked at my watch: 1 o’clock on Sunday afternoon, and I couldn’t hunt deer for another year.

I cleaned the buck carefully, pulled it mostly off the ground across a log, propped the cavity open with a stick, and let it steam while I washed my hands and arms in snow. The air was fairly warm and the snow melting, but I was glad to get back into my shirt. About that time I heard a yell. Dave waved from the top of the hogback some distance below, then trotted up the hill as if it were a level path. I regard the rubber muscles of the young with some envy.

“I heard you shoot once,” he said, “so I figured you got something.”

A child’s faith in his father is a touching thing, and I was touched. Also I was glad to see that he was packing a piece of rope as well as his rifle. (He won’t go out of camp without the rifle, on the theory that someday he’ll get a bear.) He had been at the tree where his deer hung, about a mile down the hill and two gullies over, when he heard me shoot.

If I’d tried to move my buck alone, it would inevitably have slipped to the bottom of the gully, full of brush and hard going. Dave and I together managed to slide the muley — about 200 pounds as it lay — along the slope until we got it on the reasonably open crest of the hogback. From there on I could have sat on the buck’s back and ridden down the hill, if I’d had some way to steer.

Dave helped me along for some distance, then cut across country to the considerably more difficult task of sliding his own buck down the bottom of a gully. I promised to come back and help him after I got mine to the bottom. I did just that, and when we dragged Dave’s buck to mine on the valley flat, Harold was waiting for us.

“I could hear you yelling two miles across the canyon,” he said. “So I came over to see how you were making out.”

Dave trotted back to camp, got the car, and somehow drove up to where we were without tearing out the oil pan on the rocks. By then it was dark. We loaded the deer and went back to camp, where Dave and I strung them up in a big tree while Harold cooked dinner. He’d seen about 15 does and finally decided to give up the south-facing slope and hunt on the other side. Next morning Dave and I both slept in. Harold was out of camp at daylight, walking the cow-trail road a good distance before tackling the rough north-facing slope.

Dave and I had a leisurely breakfast, washed the dishes, put the sleeping bags out in the sun, and collected a big pile of wood for the fire. About 10 o’clock we heard Harold’s Springfield roar, a single blast well up the canyon.

We drove up to where Harold’s tracks left the road and took after him. As usual, he had probably hunted with all the speed of a snail — seeing a lot of game. We found him by noon, placidly sitting beside a nice buck with high-standing antlers. It was cleaned, pulled up on a log, and propped open to cool.

“Well,” said Harold, “I was getting worried about you. I thought maybe you were still asleep. Let me carry that rifle of yours, Dave, and you and your dad can start pulling this animal around the hill. I won’t sit on it and ride until you get to the easy going down the hogback.”

He said also that hunting on this north-facing slope was not a test of skill, but of endurance.

Read Next: There Were 38 Other Public-Land Hunters Camped by Me. I Tagged a Buck Anyway

“All I did was climb up here and look across the gully,” Harold said. “This buck was gnawing on a bush, and I shot him. I’m so beat out that I don’t know whether I’ll ever make it back to camp.”

He did, though. And the next morning, when we loaded the three bucks and our camp gear on the car, it rode so low that it scraped on every blade of grass. Harold and Dave had to walk practically all the way back to the ranch while I drove, but they didn’t mind. Harold said it was our last chance for a long time to be in a place without people, and we should rejoice in it.

Read the full article here