This story, “Odyssey for a World Record,” appeared in the March 1992 issue of Outdoor Life. Today, Willmarth’s goat is ranked 7 in the world, with the world-record mountain goat measuring just one more inch than his. That billy was taken in Alaska in 2020.

Swinging around the rock outcrop crowding the turn in the road, it felt like I’d slammed into a wall. No matter how hard I pushed on the pedals, my mountain bike just hung there, suspended by the steep grade and fierce wind. Making an undignified dismount, I pushed the bike off the road behind the shelter of a boulder and took a breather. I still had five more miles of uphill travel to my campsite.

Sitting behind the rock, my thoughts shifted back to the circumstances that had led me to being here in the first place.

One spring day in 1972, Elmer Luce, a good friend who I grew up with in Holcomb, Wisconsin, had asked, “How’d you like to try bowhunting elk in Colorado this fall?”

Even as I said, “You bet!” I didn’t know where the money would come from. Wisconsin only had whitetails and black bears to hunt, so the chance to see the mountains and bowhunt elk more than outweighed the minor funding inconvenience.

My tax refund check saved the day, Elmer and I went on that hunt, and although I returned to Wisconsin afterward, I never really left Colorado. It wasn’t long before everything I owned was in my car, and I was Colorado-bound once again — this time for good. I had absolutely no idea what I’d do when I got there — besides bow hunt as much as possible. Eventually I moved to Hot Sulphur Springs, a small mountain town.

I spent the first couple of weeks in the state exploring the mountains. One of these forays took me up the highest paved road on the continent to the top of Mt. Evans, a 14,258-foot snow-covered peak that dominates the horizon west of Denver. A Colorado Division of Wildlife officer had told me that there were mountain goats in that area, and I wanted to see if I could find them.

In a day’s hiking at 12,000 to 14,000 feet, I’d seen several goats and was totally fascinated by the creatures and the terrain they lived in. I knew right then I had to try hunting goats with my bow. What I didn’t know was that it would take 11 years before I got my first chance.

Colorado offers limited licenses for mountain goat hunting in eight specific units. Six of the units are considered firearms areas where hunters may use their choice of legal hunting arms bow and arrow, muzzleloader or centerfire rifle. The other two units are open to bowhunting only. All licenses are issued by a random computer drawing, and each year the number of applicants far exceeds the available permits.

Year after year, I applied for the Mt. Evans hunting unit, and each time I received a rejection slip and the hollow feeling of having to wait until next year. But just before the application deadline for the 1985 license drawing, my bowhunting partner, Kurt Keskimaki, suggested, “Let’s change things this year and apply for tags in the roughest area there is to hunt. Maybe we’ll get lucky.”

Now, goat country anywhere is some of the most rugged terrain on the continent. Some places are nastier than others, one being the San Juan Wilderness of southwestern Colorado. Neither Kurt nor I were surprised when our bowhunting goat licenses arrived in the mail a few weeks after applying.

The day before the September 7 opening found us boarding a narrow-gauge train for a ride down the Animas River Canyon to a pre-selected drop-off point. Five hours of hard backpacking put us at 11,000 feet, on an incredibly rugged mountain range in the heart of the goat area.

We hunted hard for the first two days, but the only white we saw was snow. On the third day, just as the weather promised to break, down came a steady rain. Three days later the rain turned back to snow, and we were forced to spend the next 36 hours in our one-man backpack tents. I must have read the labels on my freeze-dried food packages at least a thousand times during those long hours.

When the weather finally broke enough so we could see, we had one day left to hunt. The last morning dawned crystal clear as Kurt and I left camp to hunt another basin to the north. Finding a white goat in all that snow seemed nearly impossible, and we alternately hiked and glassed for most of the morning. Finally, we spotted a lone goat bedded on a thin rock shelf near the top of a cliff.

Kurt had taken a fine billy a few years earlier in another area, and because I’d never had a chance at a goat, he generously insisted that I go after this one solo. He would stay in the basin to keep an eye on the animal and provide me with hand signal directions.

I hadn’t gone more than a few yards when it struck me that the traditional camouflage I was wearing just wasn’t going to work. In all that snow, I must have looked like a cricket on a white sheet. The only thing I could think to do was hunt in my white silk long underwear. So, off came my clothes, and I began the stalk of a lifetime in my long johns.

The bright sun kept me comfortably warm, but it was posing another problem. I had left my sunglasses in camp, and the sun’s brilliance reflecting off the fresh snow gave me a killer headache. Within an hour, I was having trouble seeing even large contour changes on the steep mountainside and walking became treacherous.

Even though I glassed for several more hours, I never could find the goat again. As I made my way back to where Kurt waited, my head was pounding. After 11 years of waiting for a goat license, it looked like I’d have to “wait until next year” again.

The next morning we packed out to the narrow-gauge tracks for the trip home from a miserable, disappointing hunt. While waiting for the train, I made a solemn vow: Even if it took another 11 years, I’d be ready when I drew another goat permit and things would end up differently.

Three years later, I got the chance to test that vow, and things did turn out very differently indeed — in a way I could never have dreamed possible.

Unlike previous years, the Colorado Division of Wildlife had changed the 1988 season structure in the Mt. Evans unit by splitting it into two time periods with 10 licenses allotted for each hunt. This unit had always been the one I wanted to hunt but I could never draw the license for it. Although the area was a firearms unit, I intended to bowhunt.

When filling out my 1988 goat application I reasoned that the later hunt, which opened on September 19, might be less appealing to most hunters. The only road into the area traditionally closes to motor vehicles immediately after Labor Day, limiting access to a seven to 14-mile hump on foot. A Canadian caribou hunt I had booked would also conflict with the timing of the first hunt, so the second season looked like my best possibility to draw a tag.

Wether my reasoning was on target or not, that’s the way it worked out. Finally, my name was on a permit in the area I had wanted to hunt for 14 years.

I had scouted the area every year in anticipation of getting a license, only to end up making other hunting plans after the computer spit out the drawing results. Over the years, I had located several fine trophy-class goats, but with a permit in my pocket, my scouting trips intensified. Throughout the summer, I made several trips into the area, always entering from a new direction. I was intent on finding as many good billies as possible. If I settled on one animal, there was a chance that one of the other 19 hunters might also find him and get there first. Having a couple of alternate choices seemed like the way to increase my odds of success.

A few days before leaving on the caribou hunt, I decided to make one more trip into the goat area. The hours of scouting had already paid off with the locations of several fine billies, but I wanted to take a look at a distant ridge I had never been on.

Just before daybreak, I parked my truck at a little turnout on the highway and started the four-mile hike to the ridge. As the sun rose, I alternately walked and glassed. About midmorning I spotted a single goat lying on a rocky shelf near the very top of the ridge. Even at 400 yards through my 10×25 binoculars, there was little question that this mountain goat was something special. As I cut the distance to around 100 yards, the goat spotted me and stood up.

Two other big billies I hadn’t seen also got to their feet to eyeball me. With the other two goats providing perspective, it was immediately apparent just how special the first goat was. “Those horns have got to be more than 11 inches long,” I thought to myself, but chalked the idea up to wishful thinking or goat fever. Eleven-inch horns on a mountain goat are virtually unheard of.

The standoff lasted several minutes before the goats decided I wasn’t a threat and began feeding along the ridge above me. I decided to stalk closer to get a photo.

Slowly moving into some rocks along their path, I just lay there until the billies fed into range of my 200mm lens. At 20 yards, I snapped the last frame on the roll of film and quietly slipped out of sight.

Hiking back to the truck, all I could think of was the incredible size of the goat and the worrisome prospect of someone else finding him before I got back to the mountain. Reminding myself that most of the other hunters wouldn’t get that far from the road, I headed for home to get ready for my Canada trip. On the way, I dropped the film off for processing.

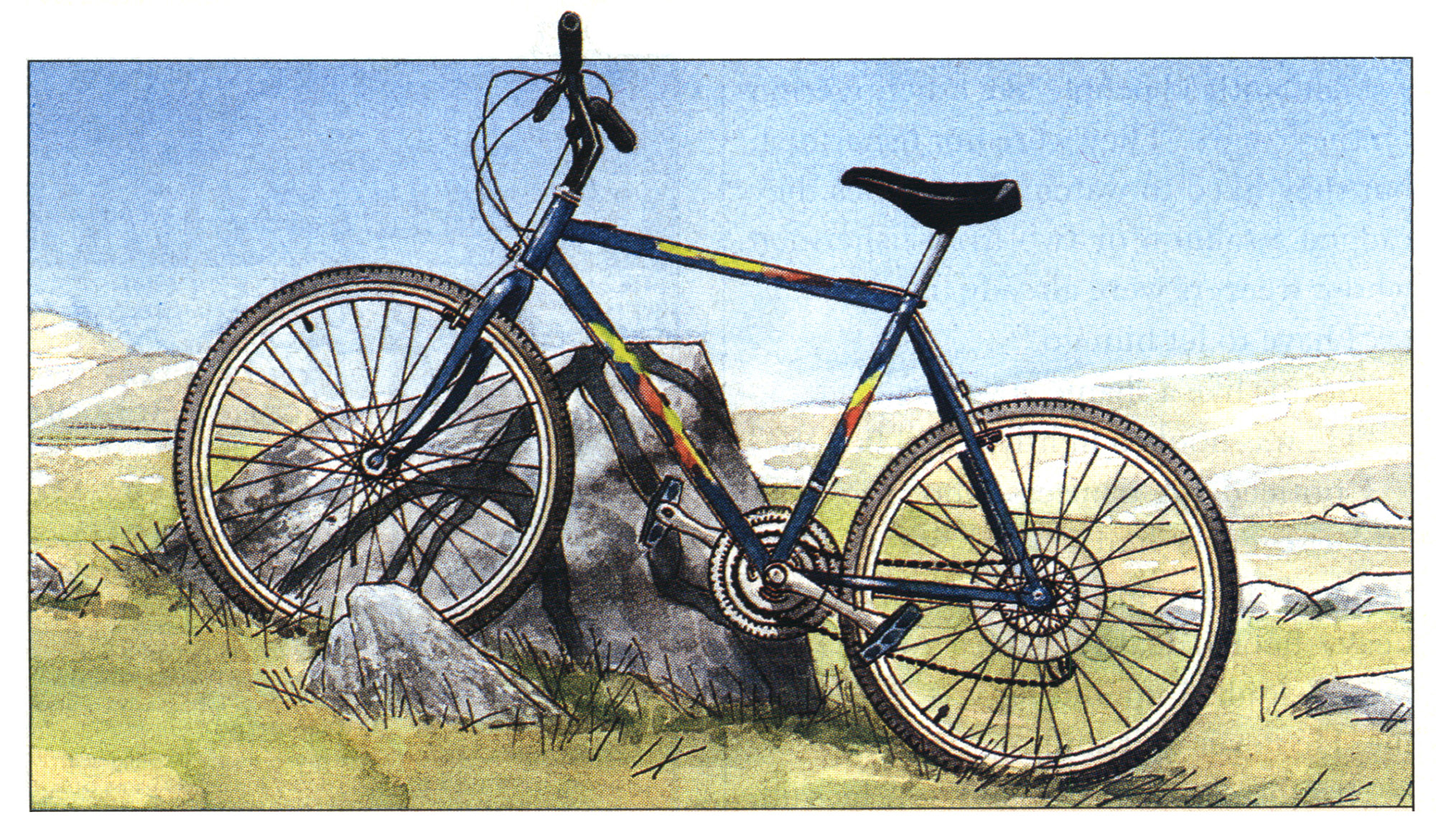

Rested now, I pushed the loaded bicycle back onto the road and began pedaling again. Just hours earlier, I had returned from a very successful caribou hunt. Kissing my wife, Linda, hello and goodbye at the same time, I started loading my truck for the goat hunt. The sea son had opened earlier in the day, and remembering the road closure, I tossed in my mountain bike at the last second.

Bucking 20 to 30 mph head winds for another five miles, I pedaled to the same pullout I’d used during my last scouting trip. Darkness had long since settled over the mountain as I quickly pitched a spar tan camp and tried to eat supper. Totally exhausted from the grueling ride, I didn’t make it through the meal before sleep overtook me.

After a very short night, daybreak and nausea pried me out of the sleeping bag. The previous day’s exertion and traveling from only 200 feet above sea level to more than 13,000 in less than 48 hours surely had something to do with my ills, but this was no time to be sick. I dressed, shouldered the pack and slowly started out along the ridge to where I’d last seen the big billy more than three weeks earlier.

Stiff winds hounded me as I hiked and glassed with no results. The morning hours slid by, and the growing fear that someone else might have already found the goat started to dominate my thoughts. I decided to cross the ridgeline for a last look at the facing mountain be fore making an early return to camp. Moments after crossing the ridge, my binoculars revealed three white specks feeding along the rocky slope about a mile away. All three billies were still there after all. The sun lit them up like beacons as they crested the mountaintop and disappeared from sight. I instantly forgot about being sick, and the wind no longer bothered me. A well-used goat trail circled the basin in that direction, and I quickly made my way to the spot on the ridge where the goats had gone out of sight.

The top of the ridge formed a large rounded knob before abruptly falling away to the south. Staying below the sky line and behind some large boulders, I slowly began to scan the mountaintop with my binoculars. About five seconds later, I found the goats right in the middle of the knob barely 100 yards away.

Dropping my pack where I sat, I nocked an arrow. Hugging the ground and staying behind rocks, I closed the distance inches at a time until just 20 yards separated me from the nearest goat.

Years of instinctive shooting practice took over and brought the 70-pound recurve into action. The arrow flashed across the alpine and disappeared just be hind the foreleg of the largest billy. All three goats broke for the south, but at 50 yards one of them went down.

Slumping back against the nearest boulder, I sat for several minutes — how long, I’m not sure — just soaking in every particle of the past few moments. It all seemed too good to be true.

Two hours later, the skinning and deboning of the meat finished, I still seemed to doubt my good fortune. Then I tried to pick up my pack. Believe me, the five miles back to camp convinced me that it all was for real.

In camp, I managed to get everything into my pack or tied on the mountain bike. Thank goodness it was all downhill to the truck. I coasted the entire 14 miles. Total exhaustion had replaced all excitement as I arrived home late that night. I still didn’t know just how good my goat was, and it didn’t really seem to matter right then. My wife, Linda, had to help me get the pack in the house, and upon seeing the horns, she put a tape on them. When the horn tips went past the 11-inch mark, I knew the goat was much better than I’d ever dreamed. I had for gotten about the photos from the scouting trip, but Linda had picked them up while I was in Canada. One of the pictures turned out to be an excellent close up of a very large goat. When we studied it on a slide screen, there was little doubt it was of the same billy I had killed.

Read Next: I Shot the Third Biggest Elk of All Time

With a final score of 52 4/8, the goat was officially recognized as the new Pope and Young Club World Record at the bowhunting club’s 1989 banquet. The score was also good enough to place the billy well up in the Boone and Crockett Club records and set a new state record for the species.

The life-size mount of that Colorado mountain goat now occupies my trophy room wall. Several plaques and the enlargement of my photo surround it.

When I reflect on the years spent trying to draw a permit and the one miserably unsuccessful hunt, all I can say is, “It was well worth the wait!”

The Mountain Bike as a Hunting Tool

This sidebar originally appeared alongside Willmarth’s story.

Do you ever get tired of that long walk to your tree stand, or hiking up that trail to the secret meadow where an elk or two can always be found?

Do you ever get tired of that long walk to your tree stand, or hiking up that trail to the secret meadow where an elk or two can always be found?

Well, there are other ways of get ting there, and they don’t have to be fed or fueled every night. Chances are you may already have this mode of transportation and probably don’t give it much thought as a hunting tool. If you own a bicycle that is less than five or six years old, the odds are about 3 to 1 that it’s a mountain bike, or all-terrain bicycle (ATB). And therein lies your ticket to faster and quieter travel on that trail to your stand or hunting area.

The meteoric rise in popularity of the fat-tired mountain bikes and off road riding is unprecedented in the industry. In just the last 10 years or so, all-terrain· bicycles have vaulted past all other bicycle types to the number one spot in sales.

According to the latest statistics from the Bicycle Wholesale Distributors Association, mountain bikes dominate sales figures with more than 65 percent market share, compared with a mere 4 percent share held by their skinny-wheeled counterparts, road bicycles.

Mountain bikes differ substantially from· road machines. The obvious variations are the thick, knobby tires on wider wheels, and the stick straight handlebars that allow an up right rider position. More subtle differences include frame geometry, balance, gear choices, stability and riding comfort in rough terrain.

Whereas most road bicycles usually have 10 to 16 gears, ATBs commonly have 18 to 24 gear selections. The lowest gear setting will rival the “granny” gear of an old Powerwagon or Willys Jeep for slow, steep climbing ability.

Seemingly, there are as many bicycle models as there are bass plugs. How does someone make an in formed choice in selecting a bike? Well, you can start by limiting your shopping to top-name manufacturers. Schwinn, Giant and Trek are generally considered the top three in sales volume. Mongoose, Specialized, Diamond Back, Cannondale, Raleigh and Miyata (in no particular order) all have a good selection of bikes.

Like most anything else, with mountain bikes you’ll get what you pay for. Prices range from about $300 to more than $1,000 for a production machine. Custom bikes can run well up into the thousands of dollars. Any extra money you spend will primarily go toward stronger frames and joints, superior metals and higher-quality components such as brakes, gears, shifters, derailers, cranks and sprockets.

Generally, mountain bikes don’t have a lot of retail price markup, so you’ll get your money’s worth for a good mountain bike. Be very cautious in selecting any of those “$159 sale specials,” however. It may be called an ATB or “mountain bike,” but it’s most likely a “city bike” with rugged looks. Riding on paved streets and parking lots may be comfortable, but put it in a true off-road situation, and the bike could prove to be unstable and not up to the task of rough-country riding.

The trail systems on many public lands are open to mountain bike travel and crisscross some of the finest big-game hunting country on the continent. In many cases, logging roads that are closed to motorized vehicles are available to pedal-powered machines. Some of these roads and trails just may get you into areas that don’t get hunted often. Who knows what you might find by using a mountain bike as a mode of hunting access?

Read the full article here