This story, “Trying to Keep Up with J.R.— No Ordinary Rabbit Hunter,” appeared in the November 1975 issue of Outdoor Life.

My feet and hands were very cold, but I tried not to notice. I stood still, shotgun in hand, and waited, as I had been doing for an eternity of 20 minutes. A hundred yards away, my Uncle J.R. was waiting with the stillness of the Sphinx and the readiness of a Mohican. The cold winter’s day was punctuated by the yelps and howls of the beagle, Nuisance, on the track of a particularly shifty cottontail.

The rabbit had been circling and backtracking with the facility of an often-chased fox, but Nuisance (Noose) was not to be denied. The circles were growing smaller, the yelps drew closer, and the rabbit was at last running toward us. I hoped and feared I would get the shot — my uncle does not understand misses.

I peered expectantly into the underbrush but saw nothing except the dog. I knew I ought to be seeing the rabbit. J.R., who can spot rabbit tracks at 25 yards in the brush from a speeding car at dusk, would have shot the cottontail long before this.

Suddenly I spotted a streaking ball of fur about 10 yards ahead of Nuisance’s nose. J.R. — well aware of my incompetence with fast-moving game — whistled. The rabbit stopped for an instant and looked quizzical. That was the break I needed. I beaded on him with the .410 and fired. That was my first and only success of the day.

There is probably no creature more defenseless than the cottontail. The rabbit’s only real means of survival is procreation, an activity he performs with epic capacity. As a result, they often abound. Armed with a 12-gauge shotgun and a minimum of skill, the man who wishes to kill cottontails rarely comes home empty-handed. The merest touch of birdshot usually kills the rabbit, and I have seen them die of fright alone. Find a brushpile, an abandoned farmhouse or barn, or a marshy swale hole, and then create a noisy disturbance to flush the rabbits. That’s rabbit killing, not to be confused with rabbit hunting.

Rabbit season in Wisconsin runs from October through January. During those months many thousands of rabbits are killed, most of them assassinated the easy way. Autumn tends to be the amateur’s time for rabbits. It’s a time when many experienced hunters are preoccupied with bows, rifles, and their effect on whitetail deer. With the coming of the snow, however, many hunters shift from buck to cottontail.

It is near the end of the season in Waupaca County, Wisconsin, and I’m hunting with my 47-year-old uncle, J.R. Simpson. For sheer cussedness, stamina, and intuition, J.R. is the best hunter in the county. Whippet-legged and hawk-eyed, J.R. has hunted every year of his life since he was 12. He’ll sit in a tree, bow in hand, patient as St. Simon Stylites, for eight or 10 hours to get his deer. With a sleepless eye he can spot and identify an animal at 200 yards in brush where field glasses and my eyes would detect nothing. In the woods he is fanatical, emotional, and demanding, and possessed of a hair-trigger temper.

It is overcast and cold, and the terrain is rugged. Horton’s Corners, a small, almost abandoned farm community north of Waupaca, is the site. The woods, fields, and marshes surrounding it are large and much more demanding than the tame brushpiles and thickets we had been hunting. We slog and hike through miles of frozen swamp, ford streams, climb hills knee-deep in snow. On this day you must love rabbit hunting in order not to hate it. J.R. wades through the woods undaunted, outhiking and outworking even the dog. This evening he will proudly display cuts and bruises.

The day begins inauspiciously with my uncle complaining about the human and dog tracks that already ribbon the snow.

“Too damn many people running around who don’t know how to hunt,” runs the refrain. Some snowmobile tracks along a ridgetop send him into tirades against “technologized society.” Like any really gifted pro, J.R. cannot abide shortcuts. The notion of hunting rabbits with a snowmobile offends his honor and pride in sacrifice. Hunting for J.R. Simpson has to be an endless challenge.

J.R.’s preferred arm for rabbit hunting is a .22 rimfire rifle. This year, though, he has once or twice adopted the 28-gauge shotgun in order to make Nuisance’s training a bit easier. During a hunt with J.R., rabbits may be fired upon only after the dog has flushed, chased, and brought them around. My finicky uncle strongly prefers that they be shot in the head so as to save as much meat as possible.

The falling temperatures and snow make scents harder than ever for Noose to detect and follow. Time and again our noble little Beagle lets out an anticipatory yelp, only to lose the track a moment later. Personally I’m just as glad to keep thrashing around in the underbrush. To stop and play the waiting game in that cold is a form of masochism.

And so the minutes become two hours, and nothing has been raised except J.R.’s hopes. He perseveres with Rooseveltian optimism. Every swale hole and each new tangle of fallen trees puts him into a fever.

“God, Steve, this is the best spot in the whole county. We’ve got to get one here!”

I am glum. My ambition is to survive and get home. I keep glancing surreptitiously at my watch, praying J.R. will call it quits. No such luck. Victory always spurs him on, but the prospect of being skunked spurs him even harder. He walks faster and thrashes harder. I marvel at how a 47-year-old man who got up at 6 that morning, cleaned his tavern, shoveled his driveway, and played 90 minutes of fierce one-on-one basketball with the local teen-aged hotshots can find the energy to work through a field like a serf at harvest time.

Finally our luck turns, or seems to. Nuisance flushes a rabbit out of nowhere and manages to hang on to the scent. With my last reserves of energy I climb atop the knoll where my uncle indicates I should receive the rabbit. The dog’s yelps have aroused J.R. something fierce. I merely hope that the dog will bring the cottontail back before I freeze.

A 1973 Dodge pulls up behind our battered station wagon, and Mr. Alan Cook, state game warden, steps out.

Noose performs her task faultlessly. I start to unsheathe my frozen right hand from the glove, but I suddenly realize (with relief) that this will be J.R.’s shot. He raises his gun, and I know the rabbit is as good as cooked. He fires once, and I prepare to congratulate him. He fires again … and a third time. It took him three shots — with a shotgun, no less — to kill one rabbit? Unheard of! I stand still and wait. Suddenly a paroxysm of curses silences even Nuisance. Great heavens, he missed!

To conceal my delight, I express condolences.

“Aw gee, J.R., Annie Oakley couldn’t have hit that rabbit.”

But my uncle pays no heed. He launches a barrage of excuses and justifications.

“This popgun has no range at all. That rabbit would be dead right now if I had my twenty-two. I think I winged him anyway.”

He quickly locates the animal’s tracks and finds some hair and blood. Like an Alabama sheriff tracking an escaped convict, J.R. sets out to find the offending rabbit. Noose and I straggle along behind with something less than lupine determination. As tired as I am, and as amused, I cannot but admire the skill with which J.R. tracks his quarry.

At length we arrive at a large brushpile. The tracks show that it is the rabbit’s final resort. J.R. gambols atop the pile like Fred Astaire, but it soon becomes clear that no amount of activity will dislodge the cottontail. The animal is probably already dead. After many a lingering kick at the branches, we head for the car.

It is getting dark when we reach it. I unload and case my gun and sink into the front seat exhausted, fully expecting to be delivered before a warm fire. No way. Uncle cannot abide to let me go home skunked. I protest that the sport is in the doing, not the killing, but to no avail. We cruise the backroads and look for cottontails. All thought of the lateness of the hour and the comforts of home have vanished from J.R.’s mind.

Near the Waupaca Conservation Club, where my grandfather and I used to run Irish setters, J.R. spots a ball of fur sitting placidly in a gully. He opens the car door for Nuisance to give chase. Pursued and pursuer disappear in a twinkling while J.R. and I get our guns out, load them, and take up our positions.

A 1973 Dodge pulls up behind our battered station wagon, and Mr. Alan Cook, state game warden, steps out. He informs us that we are hunting after hours. Hunting ends at 4:52 p.m. that day, we are told. We look at our watches; the time is 4:55. I look again. Sure enough — 4:55.

J.R. gives the warden a withering stare and insists that he’s got to shoot the rabbit or he’ll never get his dog back. With the pleasant inflexibility of a petty but kindly bureaucrat, Cook quotes chapter and verse from the code while J.R. fumes.

Dog and rabbit have meanwhile gone by tantalizingly close to the edge of the pines. Now they drift off.

With an exasperated shrug, J.R. unloads his shotgun, and the triumphant warden struts back to his car. We are left alone in the growing darkness and plummeting cold. For 60 minutes we trudge in pursuit of Nuisance, who is in turn pursuing the rabbit. Even J.R. is fatigued, and I am finding out what frostbite feels like. At 6 p.m. we arrest the dog and start back to the car. At 6:30 we drive toward town, where we encounter Mr. Alan Cook, state game warden, on the corner of Berlin and Demerest. He waves a friendly greeting.

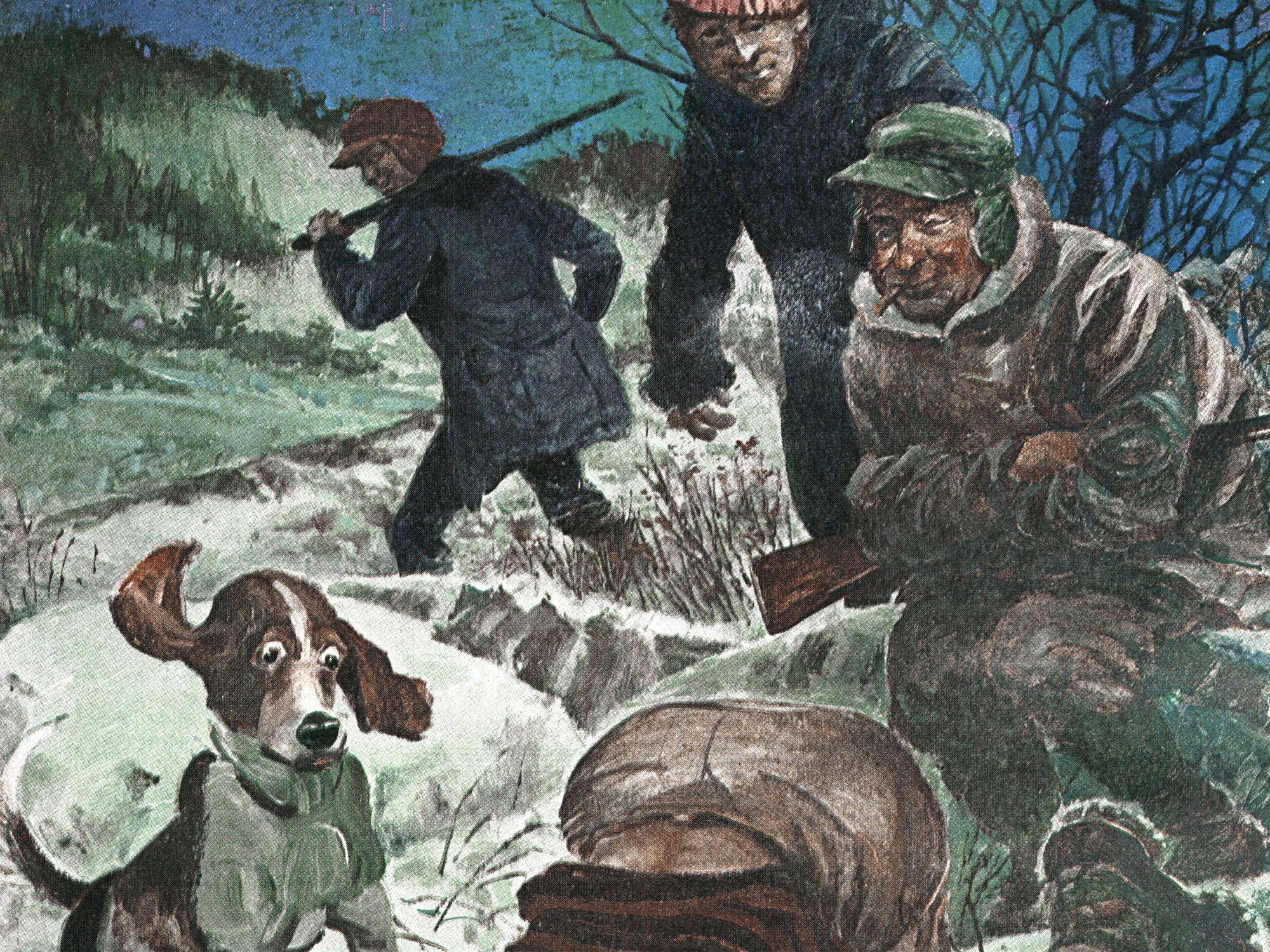

To hunt cottontails in tandem as we have been doing is unusual. More typically, rabbit hunters travel in groups. They risk confusion, but they get more rabbits. On the last day of the season, J.R. decides to hunt with several companions.

Accessible and affable in other ways, as befits a tavern keeper, J.R. is really choosy about the people he hunts with. Most of them are men of considerable age and experience; some hunted with my grandfather and knew J.R. when he was a boy. But today I am introduced to a newcomer — a young man named Skip Woodliff. He is a hard-working hunter, J.R. tells me. I learn that Skip can keep up with the most peripatetic, rarely misses a shot, and never complains or takes the easy way out.

The other man, Gene Ritschke, could have played the lead in the movie “Joe.” He has been a trusted friend of J.R.’s for 15 years. We rendezvous at Gene’s bar, the Little Norway, in the town of Scandinavia. The scene in the bar is right out of my childhood, when my grandfather and I would stop off for a bottle of pop on our way home from running the dogs. The jukebox is blaring out an accordion version of the 1950’s hit “Mary Ann” — in polka time, no less — and two farm lads are playing pool.

While he readies himself for the hunt, Gene tells J.R. and Skip about the “big brawl we had in here last night.” Attending this tale, one cannot help but regret missing the epic fight.

Gene has two Beagles. They are not held in esteem by my uncle, however, and Nuisance takes no more kindly to rivals than does her master. Herbie is a superannuated apparition-of-a-dog, but Gene stoutly insists he is only six years old — well, maybe seven. Tip, Herbie’s younger brother, will also accompany us. I never heard Tip bark once in eight hours of hunting. J.R. accedes to all this only because Gene has promised to show us a new spot that is said to be studded with rabbits as a ham is with cloves.

For sheer cussedness, stamina, and intuition, J.R. is the best hunter in the county.

During the drive, there is a discussion of rabbits and their habits, and the men sound like three proud mothers talking about their children. There are many reminiscences of days and hunts gone by, when rabbits were apparently as thick as mosquitoes in a swamp on a hot night. The unfortunate advance of civilization has cleared much underbrush, drained many swamps, and torn down most of the abandoned buildings where rabbits are wont to dwell.

In this nostalgic mood we reach the corner of Highway 49 and Elm Valley Road, where my uncle says: “In 1943 I was hunting rabbits right on this spot when Orville Dipdall brought me my orders to report to the Lake Superior Naval Base.”

“Did you drop what you were doing and go?” I inquire foolishly.

“Hell, no!” J.R. answered. “You can’t just quit hunting like that. The war was still going on when I got there.”

We drive on, and Gene finally points out the hill where we will hunt. It is distinguished from others by its desolate look. It is a mass of fallen and falling trees, gigantic snow-covered boulders, and mammoth brushpiles. It looks like Pork Chop Hill after the battle. It’s a perfect spot for rabbits. J.R. hasn’t said a word, but excitement obviously boils in his intestines.

All levity subsides. Field Marshall J.R. rapidly dictates the plan of attack. He and Skip, some 50 yards apart, will cover the top and side of the ridge; Gene will go up a gulch; I will make my way along the side of the neighboring ridge. Rabbits are to be run by whichever dog flushes them, and they are to be shot by whomsoever is in the best position.

We are scarcely ready when Nuisance flushes a big cottontail. We freeze in our tracks. The rabbit quickly circles and heads toward my uncle, but it is Skip who takes the long shot and scores. He’s lucky. If he had missed, J.R. would have erupted. In rabbit hunting as in tennis doubles, however, a successful poacher is seldom scolded. The first rabbit is in hand, and we haven’t been out of the car for five minutes.

As we launch into our separate itineraries, it shortly becomes clear that Gene will be left behind. The going is heavy, and he is preoccupied with his dogs. Herbie has a halfway decent nose, but his yelp sounds like a Beagle death rattle; Tip has an irresistible urge to follow tracks backward. J.R. dubs him Wrong Way Corrigan.

It is a wonder to me when Gene actually flushes a rabbit, which comes in my direction. Gene violates a commandment by taking an immediate shot, but Herbie is in no condition to offer chase. Birdshot whizzes past over my head. The rabbit is unfazed. I click off my safety and raise my shotgun. The rabbit is barreling at me, and I plaster him with No. 5’s at 14 yards. I glow with satisfaction, even though an antigun Senator wouldn’t have missed the shot.

Meanwhile J.R. and Skip trudge through the woods like two golems, far ahead of us campfollowers. I wonder if they’ve even heard our shots. Stuffing the rabbit into my gamebag, I proceed while Gene plods behind me, cursing his dogs. I hear Noose’s yelp in the distance off to my left and then a shot. Evidently J.R. or Skip has taken another cottontail. Lordy, we haven’t been hunting more than half an hour, and already we have three.

At length I arrive at a large boulder that affords me a panoramic view of the entire battlefield. Off to my right J.R. and Nuisance are working up the top of their hill. Down to their right Skip leaves no clump unturned and no brushpile unkicked. Gene and his dogs make slow headway up the gulch. J.R. sees where I am stationed. He signals me to linger, and I am only too happy to obey. The wild beauty of the scene transfixes me. It’s hard to take my eyes off the blue sky and the white hills to watch for cottontails.

But J.R. Simpson’s hunt leaves little time for viewing scenery. Noose’s howls and a warning call from my uncle alert me. The rabbit is bounding very swiftly up my hill ahead of Nuisance. It is a shot I would normally miss, but with my commanding position on the boulder I can wait it out and shoot at just the right time. I follow the rabbit for a long moment, and my shot is true when it comes. Skip calls his congratulations to me, but I know I would have missed on level ground.

And so it goes, this best and last day of a long season. Having flushed rabbits for the rest of us, J.R. demonstrates his peerless marksmanship later in the afternoon by shooting three absolutely unhittable cottontails. Even Gene shoots two. We walk away from that perfect spot at 4 p.m. with regrets.

And so it goes, this best and last day of a long season. Having flushed rabbits for the rest of us, J.R. demonstrates his peerless marksmanship later in the afternoon by shooting three absolutely unhittable cottontails.

Back at the station wagon, we recapitulate the day’s events like so many bridge masters reviewing their bids. When I interrupt to remind everyone that I have to be back in time to dress for the opera performance at the nearby Lawrence Conservatory, everyone breaks into gales of laughter. J.R. affects to sing the drinking song from Act I of “La Traviata.”

I renounce the opera — I didn’t feel much like going anyway — and agree to cruise the backroads looking for rabbits. Dusk is closing in on us, and nobody wants to admit it means the end of the season.

With darkness all but upon us, the novice requests to be allowed the privilege of shooting the last rabbit of the last day, and my uncle graciously consents to a roadside kill that would normally upset his tavernkeeper’s stomach.

Just south of Smokey Grenlie’s farm I spot a cottontail sitting behind a rock with only its ears and top of its head exposed. We stop the car. I get out, unease my gun, and load it. The ears and head are still visible. It is the simplest shot of the whole season. The rabbit appears to crumple, and Gene Ritschke walks over to retrieve it. When he arrives at the rock, there is no rabbit to be seen. Instead there is only a little blood and fur. Mortally wounded, the cottontail has vanished down a hole.

No hunter likes to lose wounded quarry. Gene tries his best to reach the rabbit with his hand without success. Then Skip tries, but he fails too. Eventually we shrug and start back.

But J.R., the stubborn mule, will not waste a rabbit. After doffing his coat, sweater, and glove (more than anyone else has done), he cannot reach the rabbit. He digs away as much as possible of the rim of the hole and tries once more. Still no dice. Snow clings to his face and shirt, and there are grumbles from the others, but J.R. ignores them.

“We’ll get your rabbit for you, Steve,” he says, and I admit I didn’t believe him.

He goes off and returns with a long stick that has a stubby fork at one end. He rams it down the hole. When it reaches the obstacle, he turns the crude instrument slowly and pushes hard. Then, very carefully, he tugs on the stick. Three times, the forked stick loses its freight. Then, to our amazement and J.R.’s triumph, he pulls the cottontail out on the fourth try. No magician ever produced a more-unexpected rabbit.

It is now quite dark. We hurry back to the car and drive home. We closed the season that night with all the appropriate libations.

Read the full article here