An aerial program to remove predators from caribou calving grounds in Southwest Alaska has wrapped up its second year with a total of 81 brown bears and 14 wolves killed between May 10 and June 5, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game announced on June 14. The removals are intended to improve calf survival of the Mulchatna caribou herd, which has declined by about 94 percent since 1997.

This spring ADFG employees tracked caribou in the western half of the herd’s calving grounds while patrolling for evidence of predators chasing or actively feeding on caribou. The removal of the 95 total predators was conducted on state land only, according to officials, with efforts focused on an area of about 530 square miles. That’s half the size of the 2023 predator-control area, when 104 total predators were removed (94 brown bears, five black bears, and five wolves). The herd’s eastern calving grounds were not subject to predator removal this year, as officials plan to compare calf survival between the two regions.

ADFG officials say its efforts seem to be working. Following the 2023 removals, staff documented an increase in calf survival through the fall with a caribou cow-to-calf ratio of 44 calves per 100 cows. That’s “well above the 10-year average” of 23 calves for every 100 calves, the agency notes in the release.

“Based on last fall, I anticipate we’re going to see another pretty strong showing of calves pretty quickly,” ADFG director Ryan Scott told Anchorage Daily News.

Photo by Ken Conger / N

Some calves are fitted with GPS collars, and agency employees will continue to monitor calf survival through their first year of life. ADFG plans to conduct a photo census once the Mulchatna herd arrives en masse on its summer range, as well as another herd composition survey in October.

While the state-operated killing of brown bears and wolves to help caribou has sparked controversy and a couple lawsuits, ADFG has “no population concerns for either bears or wolves” as a result of the program.

“Bear and wolf populations are healthy in western Alaska,” according to the agency, which noted that hides and skulls were salvaged when possible. “The removals of wolves and bears in the western spring calving control area are occurring in a relatively small area that is surrounded by intact habitat on state and federal lands where control activities are not occurring.”

Wolf control has been underway in the region since 2012; in March 2023, the state decided to expand those efforts with the current five-year intensive caribou management program. While the agency acknowledges that other factors like disease and habitat loss can contribute to a reduction in caribou numbers, they’re less easily addressed. Instead, “predator control is an immediate tool the department can use to attempt to reverse the herds’ decline” while officials conduct ongoing nutritional research and disease monitoring. Research from 2011 to 2021 found that predators — especially brown bears — were responsible for nearly 90 percent of newborn caribou calf deaths in the first two weeks of life.

ADFG

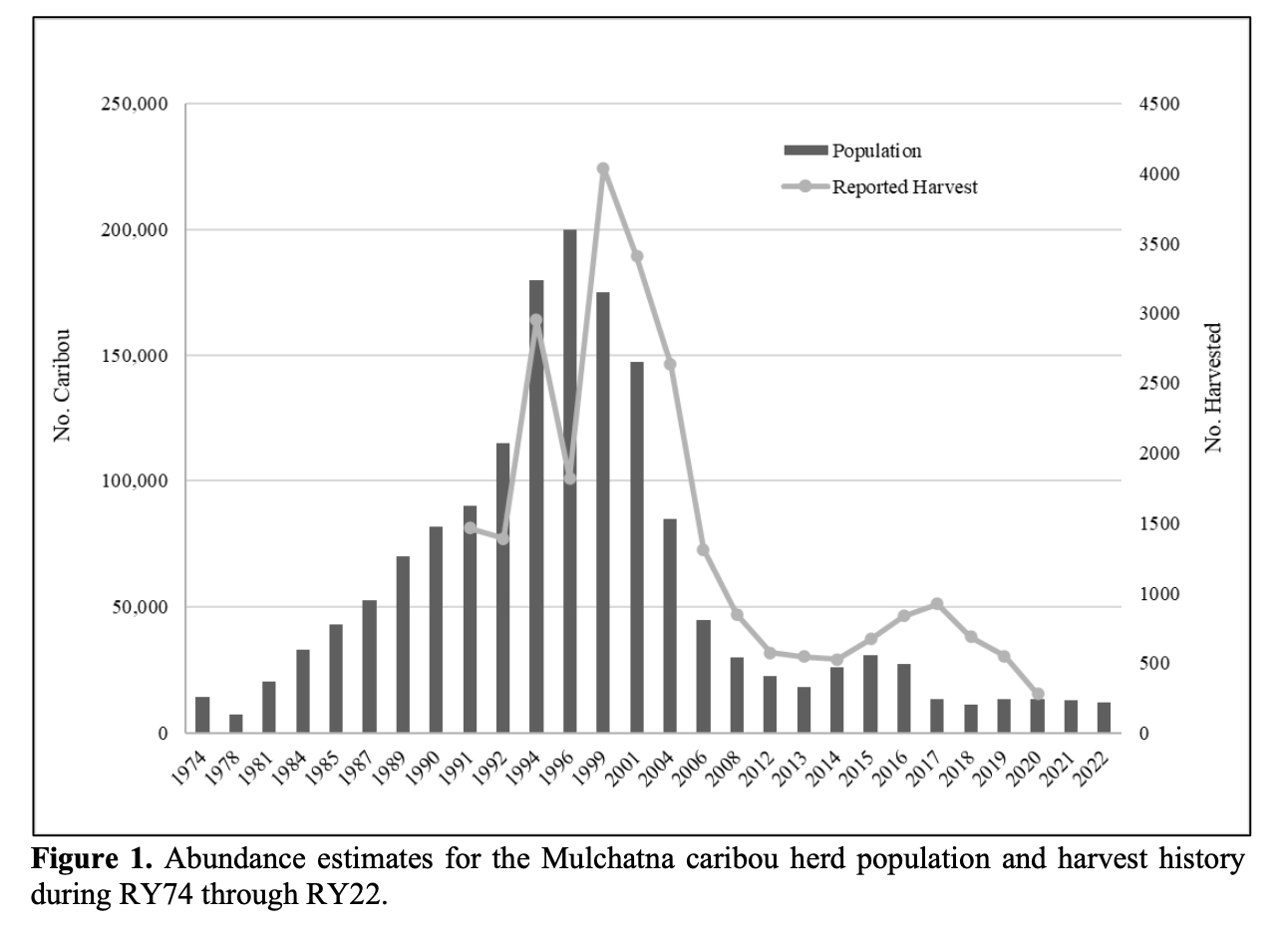

The Mulchatna herd peaked in 1997 at 200,000 animals and has since declined to a little more than 13,000 animals in 2019, where it generally remains. This is well short of the state’s management objective of 30,000 to 80,0000 caribou for the herd, which it views as necessary to sustain a huntable population. Many stakeholders remain concerned that poaching could be contributing to the low population. Hunter harvest by Native, resident, and non-resident hunters topped out in 1999 at a reported take of 4,770, but that figure sharply declined thereafter and generally followed herd population trends.

Read Next: Proposals Would Close Non-Resident Caribou Hunting in Northwest Alaska

“Unreported subsistence harvest has been documented across the range of Mulchatna and currently a multi-agency effort is underway to increase education and awareness about the hunt closure and monitor for out-of-season harvests,” the agency noted in a June 20 draft of FAQs about the intensive-management program. “Out-of-season harvest appears to occur at a similar rate as other remote areas of the state and has not had a profound impact on the population.”

The predator-removal program cost about $309,200, according to reporting by the ADN, though an estimate for this year’s program wasn’t yet available. ADFG officials were not immediately available for comment.

Read the full article here