WE HEARD OUR FIRST gobbler a few minutes before 5:30 a.m. As gray dawn seeped into the mountain woods, the wildlife symphony rang down the ridges and through the high coves. A cardinal was in full voice on the ridge just above us, and the other mountain birds took up the chorus. Crows cawed in the distance, a barred owl was on his bass cello, and a big pileated woodpecker drummed on his hollow tree. The gobbler’s notes made an exciting background.

“Sounds like an old graybeard,” Bob Card said under his breath.

We stood just beneath the crest of Duffy Ridge, a long, forested spur that drops off from the bulky outline of Sylco Mountain in Tennessee’s Ocoee Wildlife Management Area, which lies snug up against the Georgia line.

“Why don’t you go after him?” I whispered. “I’ll stalk the next old tom that sounds off.”

Bob cocked his head. “Listen!”

“I heard him,” I said. “It’s another bird at the end of this ridge. He should be right close to where we left Bill Ewing.”

Near by a turkey hen added her musical yelps to the growing melody. Her music had an ethereal quality, and we could not quite tell the direction. Then west of us two more toms made the hills ring. Bob chuckled under his breath.

“Four gobblers. This must be the convention site. One sounded from that high ridge where Earl Cady was heading, and one between here and there. You go after the closest bird, and I’ll try the first one.”

I didn’t need any wattle-twisting. I liked the sound of that old tom’s ringing challenge. It told me that I had a job cut out for me.

“Good luck,” I whispered. Bob nodded, his eyes bright.

I turned left on the main ridge and embarked on one of the most exciting days I ever spent in mountain turkey woods.

Dr. Robert S. Hines of Cleveland, Tennessee, had invited me up to his annual spring gobbler hunt on the Ocoee. Doc and I have been outdoor partners for almost a quarter-century. I consider him an outdoorsman with an avocation in dentistry.

Doc is one of the top turkey hunters in his part of the range. The day before I arrived he had killed a gobbler outside the management area. He did it in the orthodox manner too, by simply calling a tom close enough for a lethal load of No. 4’s, which he prefers.

The law allows a hunter to take another gobbler inside the wildlife management area. Doc Hines and I each had hunted turkeys previously on the Ocoee, but not together. I’d found his tracks in a few places, and he must have seen some I’d left here and there.But most of my hunting had been south around the Georgia line, while the northern half of the WMA was more convenient for Doc.

The other hunters in our group were Bob Card, a car dealer who was host of our party at his cabin on Ocoee Lake; Bill Ewing, a banker; and Roger Hanger, all three from Cleveland, Tennessee. Earl Cady was a professor of forestry at the University of Tennessee, and Larry Graf, Jack Feiereisen, and Dr. David Dunn were all from Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin. David is a pediatric neurosurgeon who was on the Olympic bobsled team.

A resident hunting license costs $5, a nonresident one $25, plus a $5 stamp and a $5 WMA permit. We had started our hunt the day before. That first morning two of our party had almost scored.

Bill Ewing was on the end of a long ridge where he heard a gobbler at sunup. The tom answered his yelps a few times, and Bill sat down in a screen of bushes with his back to a broad oak and his gun ready. He yelped three or four more times, without getting an answer. Gnats chewed his face and neck, a root dug into his rear, and his arms ached from holding his gun up. But he suffered there for 30 minutes without getting another peep out of the tom.

When a gobbler that has been excited by the yelping suddenly shuts up, you can usually count on one of two things: either he is spooked and heading the other way or he is stealthily approaching to investigate.

After half an hour Bill decided he’d hit a false note or goofed some other way. He laid his

gun down, got up, and rubbed his paralyzed parts. He stepped out of the blind without his gun, walked a few yards behind the tree, and lighted a cigarette.

Six puffs later he craned his neck around the tree. Two gobblers stood no more than 30 feet in front of his blind. When they saw his movement, they disappeared as if they had been erased.

“If I’d just stayed three minutes longer … ,” Bill wailed later.

Doc was slowly cruising along a ridge that first morning, pausing every 100 yards or so to cluck and yelp softly-which is often the way to locate a bird when it is not in a gobbling or traveling mood. He got an answer — not a gobble, but the inquiring yowk-yowk-yowk of a big tom. He sat right down against a tree and dropped his camouflage mask over his face.

After a few minutes he yelped again, and the gobbler appeared, partly hidden in a brush patch some 50 yards away. The bird was curious and stood long minutes until Doc clucked again. Then it slowly moved 15 yards closer. For a long time it remained, partly hidden by a tree. Then it stuck out its head and neck to study Doc’s motionless bulk against the oak. Doc had his sights on the head and figured that at 35 yards he couldn’t miss. He shot. The woods erupted with half a dozen hens. He ran down to pick up his gobbler. It wasn’t there. He couldn’t find even a feather.

He paced off the distance and was chagrined to learn that the bird had been out 50 to 55 yards.

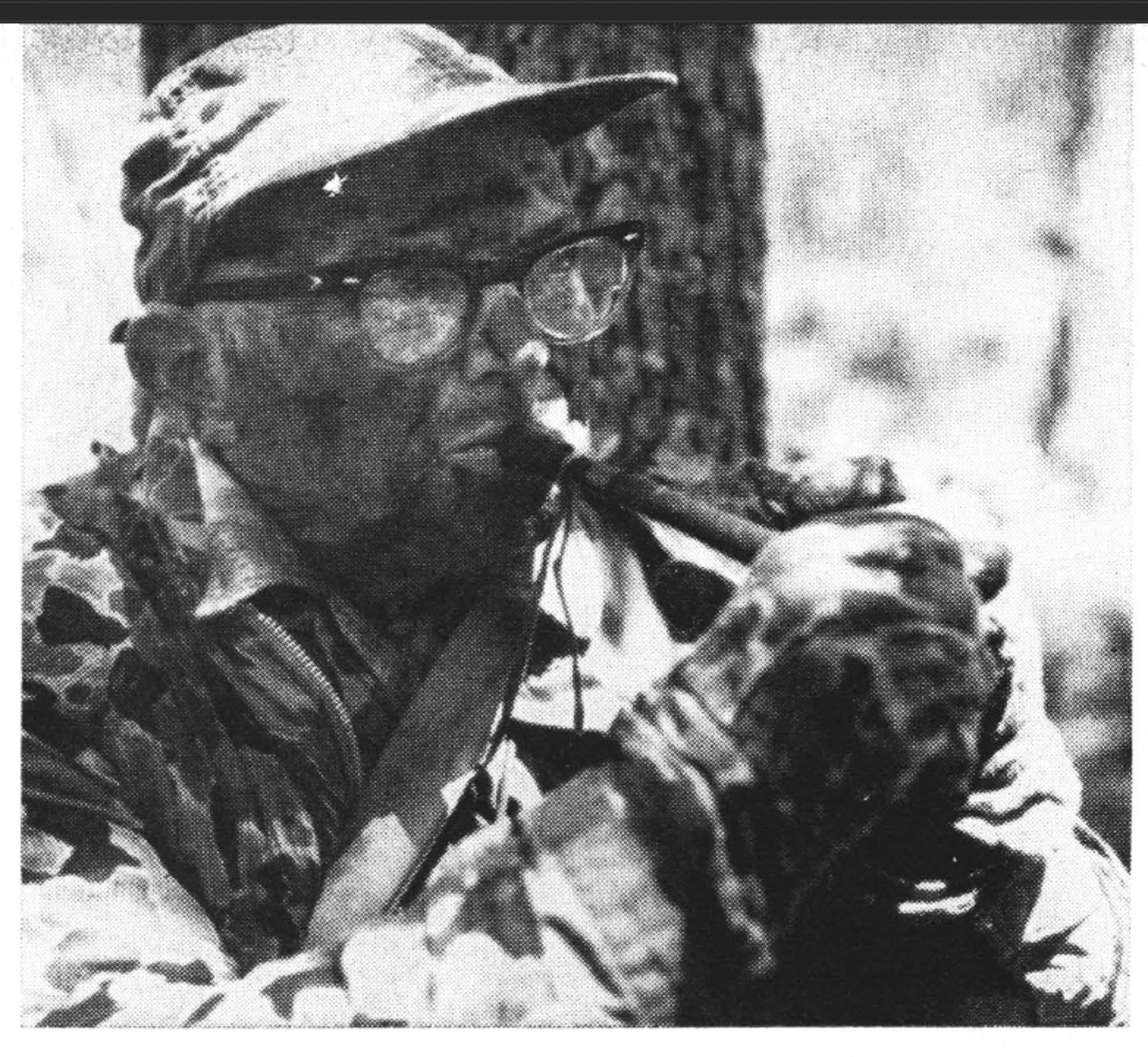

“I’ll never wear a face mask again,” he swore, blaming the veil for his error. “From now on it’s bowhunter’s paint, like you use.”

That first morning I almost had a chance at a gobbler. Bob Card and I heard him gobble across a creek valley, and I went after him. The trick is to get close to a gobbling bird without letting him see you. Then find a natural blind of logs or brush, or make one by surrounding yourself with leafy limbs stuck around a tree trunk, which you can lean against so you won’t be silhouetted against an open background.

The forest vegetation was thick. I got within 150 yards of the gobbler and paused on a slope to pinpoint him before I moved closer. I heard a yelp.

It was either a hen or another hunter, so I sat down until I was sure. The notes sounded genuine, except for three things. They came a little too frequently, and from a fixed location, and there were too many notes in each sequence. A hen may vary her notes, but seldom does she remain in one spot. She will usually go to the gobbler. I concluded that some other hunter was working this tom.

To keep from disturbing him, I backed off up the hill on my side of the creek. I built a blind and sat down to see what would happen. If the turkey came on my side of the stream, I was determined to try him. But he went the other way. The last time I heard him he was high on the mountain.

Now it was a new day. The gobblers were ready for romance, and someone in our group should be lucky.

Earl Cady had gone to the farther high ridge. Two birds seemed to be gobbling there-one between the hogback and the creek valley and the other higher. I did not want to disturb Earl, so I chose the lower middle ridge. I hoped I could make my calls seductive enough to bring the nearest bird all the way across the wide creek valley.

I selected a spot almost directly across the valley from the nearest bird I’d heard. Sixty yards beyond, the ridge broke off sharply in three directions. Had I stopped too close to this break I would have been at a disadvantage, since a turkey coming up the mountain would be almost in my lap before I saw it. Having open vision for 60 yards gave me time to get my gun up. I could let the tom approach close enough so that no matter what happened I couldn’t miss.

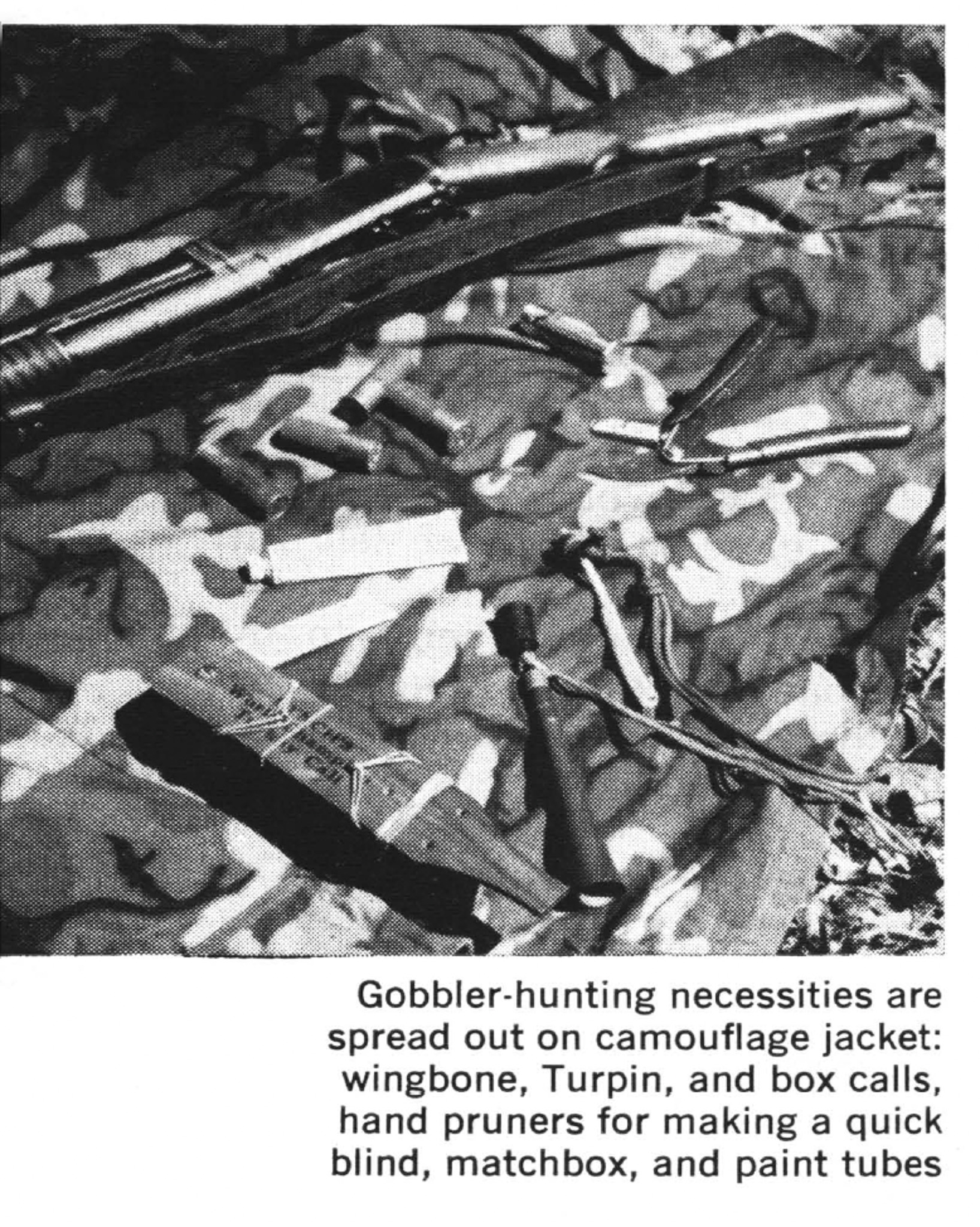

The tree I leaned against allowed an open view on three sides. I built my blind quicker than usual. After 50 years of turkey hunting, I thought I knew all the tricks, but Doc Hines had taught me a new one. Doc carries a small pair of pruners in his coat pocket. Instead of using a knife to cut through inch-thick or larger branches, often with a cracking noise, he simply snips them off with the pruners.

He had insisted I bring an extra pair along. Don’t build a blind so thick that you can’t see out of it. Make it just thick enough to break up your outline with about a 30 percent screen of leaves. Place the branches far enough away that they will not interfere with the movement of your gun barrel.

After I finished my blind I scratched out a place to sit and took off my shoulder bag containing a compass, box caller, waterproof matchbox, cord, camouflage, a few extra shells, and a light rainsuit. For three days the weatherman had predicted rain, but this dawn was clear. I set my gobbling box, which I also use occasionally for yelping, within easy reach.

I sounded three hen notes, waited a few seconds, and repeated them. The gobbler answered immediately. If I have a gobbling bird pinpointed, I always sit down before I make those first notes. A number of times I have yelped, moved, and had the bird come in to where I called the first time. Over many years I have used about every kind of call and have taken gobblers with a good many. I finally boiled them down to three types — gobbling box, wingbone, and diaphragm used on the roof of the mouth.

The gobbling box will often arouse an old tom that nothing else can stir. He thinks he has competition in his territory. The box also can be yelped, and the sound carries much farther than do my other yelpers.

Read Next: The Best Turkey Calls, Tested and Reviewed

I hang two of the wingbone type around my neck. One is the effective Turpin yelper, a favorite in Pennsylvania. The other is of small wingbones, made for me by Dwain Bland, an old turkey-hunting partner in Oklahoma. Both wingbones make softer, more musical notes than the box does. You can work the diaphragm call without using your hands or making any other movements to catch a turkey’s eye. I had on my water-soluble bowhunter’s paint to camouflage my face, and I wore camouflage mesh gloves, because the paint tends to rub off the hands. I was ready for action. I hoped the gobbler across the creek felt the same way.

He gobbled twice in five minutes. I waited awhile before making a series of yelps on my wingbone. He answered immediately. I smirked. My gobbler was on his way, I told myself. The only predictable thing about turkeys is that they are unpredictable.

That tom gobbled once more and shut up. Two or three times I tried inquiring yelps, without an answer. That other feathered buck near the crest seemed to be moving away, but he continued to sing to the world. I had an inclination to go after him, but he was in Earl’s territory. Besides, my bird might be on the way. So I stifled my impatience and settled down.

Patience is the most valuable prerequisite of a turkey hunter. When little is happening you want to look for action elsewhere. Only a load of willpower can make you wait. I forced myself to sit in that blind for 1½ hours. My patience ran out at last. I got up and moved down the ridge, stopping every 100 yards to cluck and then to yelp. I wanted to cross the valley and tackle that next ridge where I had last heard a tom, but some inner urge kept pushing me back to that blind.

I made my way slowly back uphill, pausing often to listen, but not a turkey sound could I hear. When I stepped into the blind and sat against the tree, I felt I had come home again. I was sure of it when I yelped on the wingbone and got an immediate answer from across the valley. That bird made the woods ring, and he started two more toms on the ridge above him.

How much yelping should a hunter do? A fellow can easily get overanxious and call too much. If I were a gobbler, I’d figure I had the hen so hot and bothered that she would come to me. It’s better to yelp just enough; let the tom’s imagination do the rest. Many master turkey hunters wait 10 minutes or longer before they call again.

Precede the yelp with a cluck, and listen intently for half a minute or so. If the gobbler is sneaking up, he’ll often answer the cluck, and if he’s close enough, it will bring him right in.

I went through this cluck-and-call ritual, but when my bird gobbled again, he sounded higher on the ridge. This time he stirred up three gobblers on the mountain. These got two more going. My tom sounded off again. He seemed to be moving along the ridge. I knew better, but I made a big mistake. Usually a hunter should not leave a place once the birds have him located. But I figured that if I moved about 300 yards to where the valley narrowed, across from where my turkey was traveling, he might cross over to me.

I went around the rim and with the hand pruners set up a quick blind. My next yelp was greeted with dead silence. I waited five minutes and yelped again. No answer. After another five minutes I tried again and got more silence. No one had to tell me that I had made a stupid move and that I’d better get back to my original blind.

When I returned, my yelp was answered loud and clear by the four gobblers across the valley and apparently by the two birds I had first heard on the end of the ridge, which by now had moved much closer. I was surrounded by six gobblers, all making music. Not many hunters have had that happen, and it sent my systolic pressure zooming.

I kept my ears tuned for the lightest cluck or footsteps in the leaves. A heavy, walking gobbler often makes as much noise as a man. I let minutes go by before I tried a cluck. It was answered instantly by two birds that were in a Iittle hollow almost behind me.

I squirmed around until I was half on my side, facing the hollow and the ridge that hid it. The turkeys sounded no more than 30 yards away. All I could do was lie motionless and wait for one to stick its head over the ridge.

For 30 minutes I lay tense, cramped, and ready, clucking occasionally, with the two birds making the forest roll with sound. But they would not come closer. Then they slowly began to drift up the ridge, still gobbling. My birds across the hollow had not uttered a note. I felt like running after one, tapping it on the shoulder, and saying: “Look, old buddy, I’m not going to hurt you. All I want to know is what I did wrong.”

In desperation I gobbled my box. The twoo toms turned back, gobbling every few steps. This time I felt sure of a shot. But they stopped again in the little hollow and stayed another quarter-hour. It was enough to tear a man up inside.

They retreated once more. I tried again to bring them back with the gobbling box. This time they kept going.

All the music, however, had stirred up the four birds across the valley. They continued strong for more than a quarter-hour, and then they too fell silent.

I was about as low as a turkey hunter can get. I apparently had goofed with six eager toms all around me. I was so discouraged that I did the best possible thing under the circumstances — nothing. I thought of lighting my pipe, but I had no taste for that. I considered gathering up my gear and starting down the mountain. But I just didn’t feel like moving. It seemed an inglorious end to a glorious morning. Gobble – obble – obble. GOBBLE-OBBLE- OBBLE!

I almost jumped out of my blind. It took me a few seconds to realize that the sound had been double-barreled and could have been made by two gobblers — one or both out in front, just low the hilltop. If they had walked up without announcing themselves, they’d have caught me with my wattles down. Experience and instinct made me lift my Winchester 12-gauge Model 12 and brace it against my knee in front of me. A hunter can hold this position a long time.

Just as I got that gun up, a gobbler’s head appeared from behind a lump of brush some 50 yards away. He made a critical survey of the scene, including me, but I’m sure he saw me only as a camouflaged blob. He walked around the brush, gobbled, and went into a strut, his head down against his breast, his feathers fluffed, and his big tail in a colorful fan.

Then he smoothed his feathers and came toward me, his wattles red. He went into a half strut with a little dance; then he lifted his head and stood for a half-minute looking directly at me. He slowly walked a few more yards. When a turkey is moving toward you, it’s best to let him get well within range.

Read Next: The Best Turkey Hunting Shotguns, Tested and Reviewed

But this big bird stopped and raised his head as though he were suddenly suspicious. In a split second he could step behind a tree and vanish. I guessed the range was about 35 yards, so I took no more chances. With the sights on his head I squeezed the trigger.

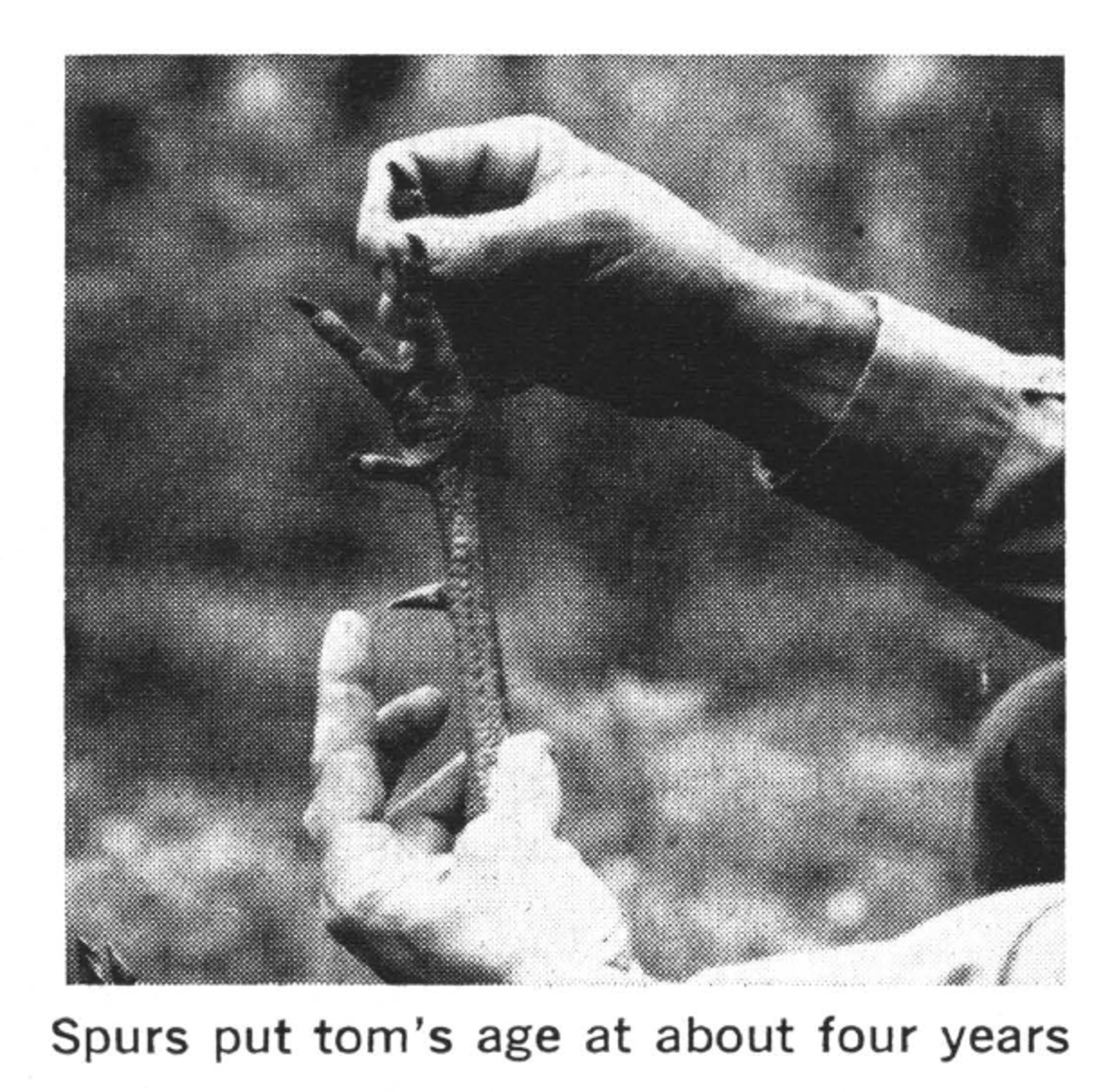

He went down under the impact of my high-powered No. 6 shot. The gobbler weighed 17 pounds. His heavy 10.5-inch beard and sharp spurs indicated he was about four years old, well into a mountain gobbler’s prime.

I looked at my watch. Ten-forty. I admired my gobbler that had taken more than 4.5 hours to bag. I realized this was one of the finest mornings I’d ever had in turkey woods.

This story, “At the Gobbler Party,” first ran in the March 1974 issue of Outdoor Life.

Read the full article here