Mishaps are a part of hunting. We’ve all experienced a few. Some of mine have been deadly serious, but most I can chuckle about now. What matters is that each misstep has taught me something. And though some of the lessons have been painfully frustrating, all have made me a better hunter. Here are some of my favorite misadventures.

Northern Exposure

On a recent whitetail hunt in Saskatchewan, I didn’t see the kind of whitetail I was looking for, but my pal Gary Clancy took a modest buck.

Since Gary had flown to Canada and I had driven my pickup, he gave me the deer to take home. Returning to the U.S., I checked in at a remote customs office on the border and filled out the routine paperwork. The buck was properly tagged, and Gary had written a donation slip transferring the deer to me. All was in order — or so I thought.

The U.S. customs agent, whom I knew from earlier border crossings, asked me if I had an export permit, since I wasn’t the person who had killed the buck. Never having brought someone else’s deer back with me, I wasn’t aware of the requirement.

The U.S. agent then suggested I walk across the street and check with the Canadian agent, who kindly informed me that I had to get the permit from a Canadian wildlife officer. Problem was, it was noon on Sunday and all the wildlife offices were closed. Worse yet, it was Grey Cup Day — the Canadian equivalent of Super Bowl Sunday. I had to be home that evening in order to get ready for another trip the next day, and it was an eight-hour drive from the border to my house.

Finding a game warden on the biggest pro-football day of the Canadian season might be impossible; nevertheless, I had no choice but to try, which meant a drive to the nearest wildlife office 100 miles north.

After two hours of fighting my way up, I heard music coming from over the ridge: the Beach Boys.

When I arrived at the town where the office was located, I stopped at a gas station and asked if anyone knew where a game warden lived. The attendant called a warden who lived nearby, and within the hour — after the warden had shown me a bunch of his trophies — I was headed back south with the permit.

This time I crossed at a different customs station because it was closer. A week later, a U.S. federal agent called me at home and said he wanted to have a little chat.

“Bring your paperwork and permits from your deer hunt in Canada,” he said. As it turned out, all was proper, so I asked why he was investigating my hunt.

“The computers caught you,” the agent said. “You tried to enter the U.S. at one customs station, were denied, and then entered through another station a few hours later. It smelled fishy, but you’re clean.”

Clancy’s buck, by the way, was delicious, despite the hassle.

Doing Hard Time

The only other time I had any dealings with law enforcement officers on a hunt was on a mule deer trip in Utah. I was hunting with a bunch of college classmates, and we were on a meat mission. As struggling young foresters we needed all the venison we could legally get to fill our freezers.

We borrowed a homemade trailer from one of our professors and had hunted only a half-day before a blizzard struck. A warden drove by our camp and warned us that three feet of snow were on the way. We loaded just one scrawny doe in the trailer that we had hoped would be full of deer, and we headed home. The tow vehicle was a ’56 Dodge sedan that my grandfather had given me. It had chains on all four tires, and we took our place in the long line of hunters who were making an exodus from the mountains.

Suddenly, a driver behind us decided to pass several cars at a time. He saw oncoming headlights, tried to scoot back in line and crashed into the side of my car, sending us and the borrowed trailer over the guardrail. The car did a complete roll, landing right-side up. Miraculously, six terrified young men got out without a scratch.

The trailer was demolished, the car was totaled and the nearest town had no motel rooms because of the blizzard. Friends from college could pick us up the next day, but we had no place to sleep that night. Then the sheriff who investigated the accident had an idea.

“How’d you guys like to spend the night in jail?” he asked.

“As long as you don’t lock the door, sign us up,” one of our gang said. And so we spent the night warm and comfortable in the slammer; the only problem was that I lay awake all night figuring out how to tell my Dad the car was wrecked and the professor that his homemade trailer was history. We managed to salvage the doe, however.

The Ice Man Cometh

Another college incident that wasn’t funny occurred almost 40 years ago, when I was studying forestry at Paul Smiths College in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. My classmates and I lived in an off-campus dormitory well off the beaten track several miles into the woods.

One evening during deer season, my roommate, Dave, didn’t return on time.

When he still didn’t show up after a few hours, we weren’t too worried. Dave was the finest woodsman in our bunch.

As more hours passed, however, we became worried. It was 25 degrees below zero and two feet of snow blanketed the woods. Skilled or not, Dave should have been back. We knew he couldn’t be lost because he was too good a woodsman, but we were concerned that he was hurt. He wouldn’t last long in the bitter cold if he couldn’t get a fire going.

We were just organizing a search party when we heard a loud thump at the door. It was Dave — semiconscious, almost delirious and suffering from hypothermia. Somehow he had crawled and dragged himself the last quarter-mile to the dormitory. The thump we heard was his fist as he managed to draw enough strength to punch at the door.

Dave was in big trouble. His legs and boots were encased in ice an inch thick. There was hardly any movement possible at his knees — he walked as if he were on stilts.

It was impossible to remove his frozen pants and boots without cutting them off, so we slowly immersed his lower torso into a bath of lukewarm water. When he was thawed, we got him into dry clothes and rushed him to a hospital 20 miles away.

The doctors weren’t optimistic when they examined him and initially considered amputating both of Dave’s legs. Luckily, that didn’t happen, though Dave did suffer serious frostbite. His troubles in the woods had begun after he had shot a big buck close to dark and taken a shortcut across a frozen beaver pond instead of going around it. He broke through the ice and fell into freezing water up to his waist, but fortunately he was able to get out. His clothing, however, froze quickly, entombing him in a cocoon of ice. It had taken all his skill and strength to get himself back to safety.

Mule Deer Mix-Up

Years ago, when I lived in Utah, I was looking for a good muley buck just across the Wyoming border with my son Dan, who was nine at the time.

Dan and I spotted three big bucks just before sunrise. They were 200 yards out, in good range for my .30/06, but my binoculars revealed a problem. A legal buck had to have four points on at least one side, and these bucks, all of them massive 2 7- to 2 8-inchers, had only three points to a side.

I couldn’t believe it. Surely one of those deer had to have a fourth tine. The odds of three huge bucks all being three-pointers were slim. I wore out my binoculars — and my eyeballs — glassing the trio over and over. Unbelievably, none of them had a fourth point.

Later, Dan and I were eating lunch in the truck when a warden drove up.

“Any luck?” he asked.

“Just a few really big three-pointers,” I answered. “We didn’t see any legal bucks.”

The warden furrowed his eyebrows.

“You mean none of those bucks had brow tines?” he asked. “In Wyoming, brow tines count as a point.”

You could have knocked me over with a feather. Every one of those dandy bucks had brow tines. In Utah, where I lived, brow tines didn’t count. It was a dumb move on my part, and you can bet that to this day I read regulations thoroughly.

Help Me, Rhonda

Once I trailed a Wyoming muley up a steep mountain, but then lost his track halfway up a rockslide. I had never been to that area before, but I decided to climb to the top. It was miserable going, with loose talus that slid away underfoot. I’d climb three steps and fall back two. Finally, after two hours of sweating and fighting my way up, I neared the top. I heard music coming from over the ridge.

Music? My brain must really be fried, I thought.

As I stumbled to the crest, the music grew louder. The Beach Boys!

Imagine my surprise when I looked over the top and saw a new Chevy pickup parked on a well-graded road. A young couple were sitting in the truck. He was peering through a spotting scope. She was looking bored. I was looking mad.

When the man saw me he looked shocked.

“Where’d you come from?” he asked.

“Down there,” I said. “See that blue dot? That’s my pickup.”

“You mean you climbed this cliff? Man, you must be nuts!”

Buck of a Lifetime

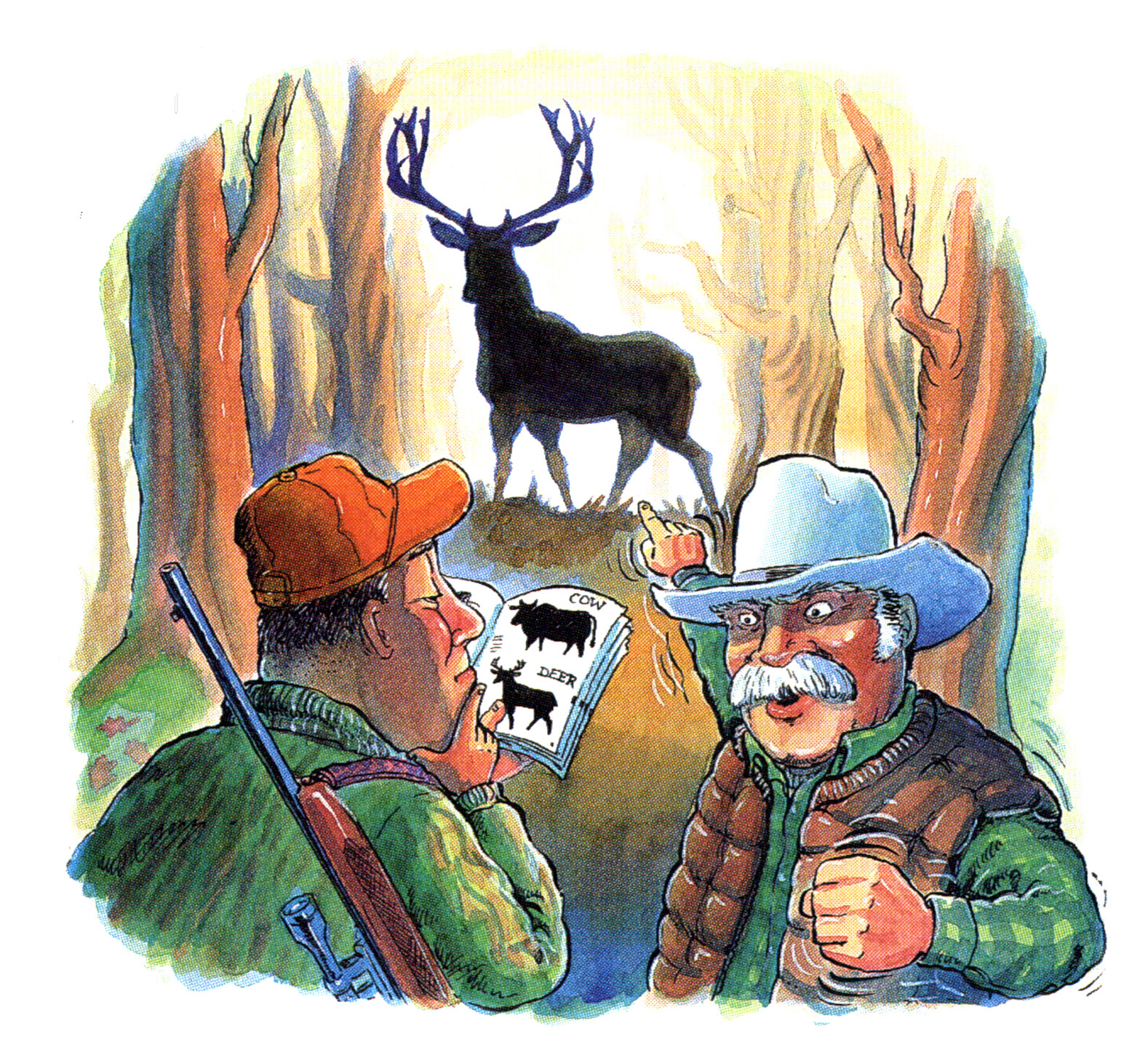

One of my most frustrating experiences occurred during a Wyoming mule deer hunt. I had already taken my buck and was riding along with an out outfitter pal and his client. The outfitter’s horse was about 10 yards in front of us and had rounded a turn in the trail when an enormous buck flushed from some brush and bounded off. The huge deer suddenly stopped and turned around to look at us from a ridge 70 yards away.

To my complete astonishment, the hunter stayed in the saddle, staring at the deer.

“Get off the horse and shoot that buck,” I yelled.

As the fellow dismounted, I piled off my horse, grabbed the reins of both animals, and waited for the guy to shoot. To my dismay, he stood there on the trail, aiming at the deer … and aiming … and aiming.

“Shoot!” I screamed. “Hurry and shoot!”

Still there was no shot.

“What are you waiting for?” I shrieked.

“That’s no buck,” the man said calmly. “That’s a bull elk.”

“Shoot!” I screamed. “Hurry and shoot!”

“That’s no buck,” the man said calmly. “That’s a bull elk.”

I was dumbfounded.

“It’s a buck,” I gasped. “The biggest mule deer you’ll ever see in your life!”

The man didn’t believe me. This was his first western hunt. He had never seen a muley buck before and had no idea what a super-buck looked like, let alone a bull elk.

Predictably, the giant buck leaped over the rim and disappeared. Suddenly the outfitter appeared, riding briskly toward us. He was steaming.

“Didn’t you see that monster buck?” he asked. “It would have made the record book for sure.”

A look of anguish swept over the hunter’s face. We rode the rest of the trail in silence.

He Who Hesitates

A similar thing happened in Montana to a friend from the East who was inexperienced in western hunting. He was with a guide who was as good a hunter as any I’ve known. This veteran woodsman was the quiet type and generally kept to himself, but when he said something, it was usually something important.

As we were riding, a huge buck jumped up and ran for the hilltop, where it stopped and looked back.

Very calmly, the guide said, “Get off your horse and shoot that buck.”

The hunter dismounted, but instead of heeding the guide’s advice, he glassed the buck with his binoculars.

“How big is it?” my easterner pal asked.

“Just shoot,” the guide said quietly.

“Will it go 30 inches?” my friend asked.

“Shoot!” the guide said, the urgency building in his voice.

Finally the hunter retrieved his rifle from its scabbard. Before he could shoulder the gun, the buck took off. Later, I asked the guide privately how big the mule buck was.

He thought about it a moment, stuffed a chew in his mouth and said, “Biggest damned buck I’ve ever seen in Montana.”

This story, “Deer Hunts to Remember,” appeared in the February 1999 issue of Outdoor Life. For information on autographed copies of Jim Zumbo’s books, check his website at www.JimZumbo.com.

Read the full article here