This story, “Mako!” appeared in the March 1978 issue of Outdoor Life. It was published just three years after the blockbuster “Jaws” hit theaters.

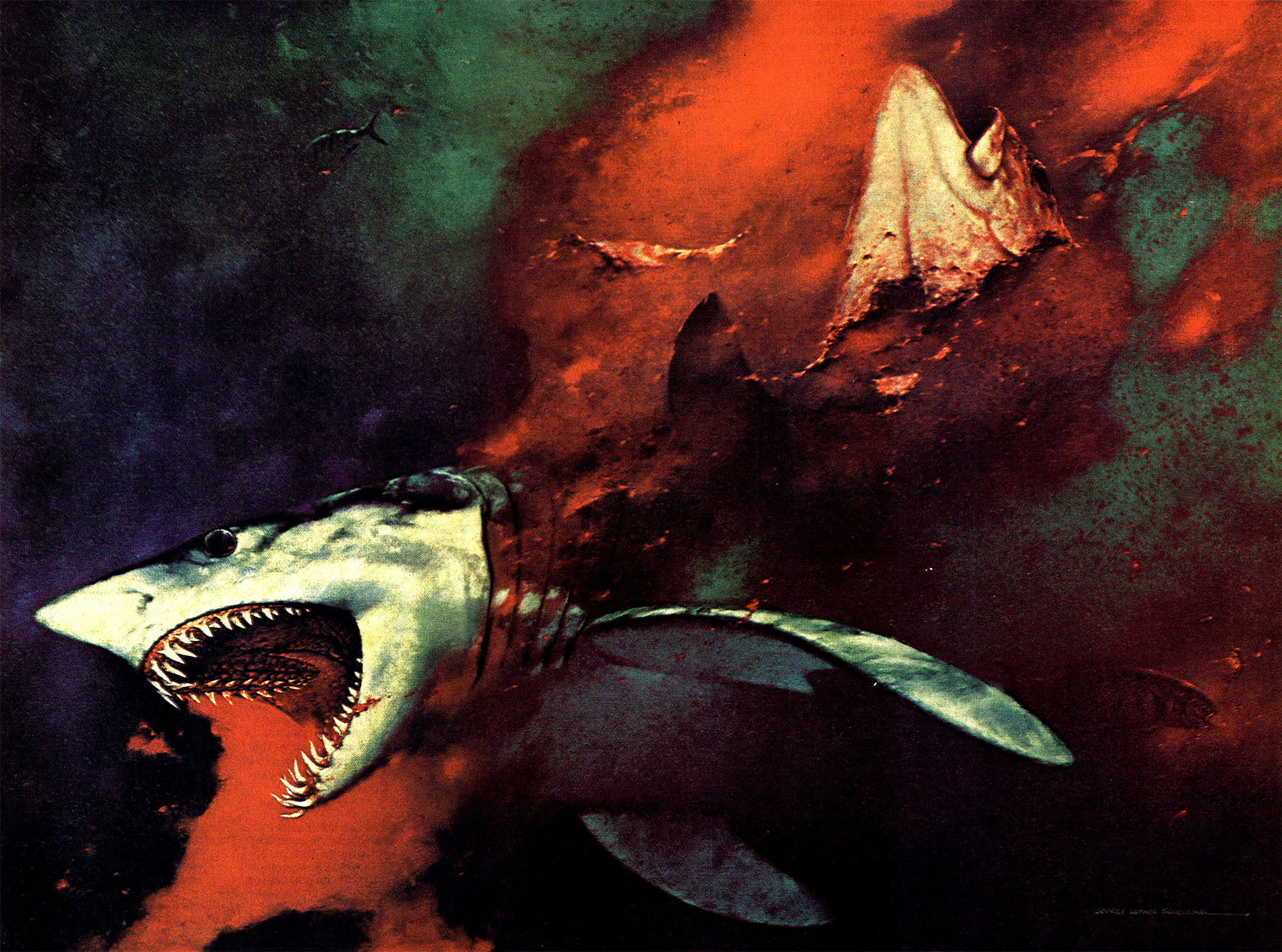

The mako prowls its shadowy underworld with an arrogant confidence, propelled by languid sweeps of his large tail. All else is motionless, except for the slight tilt of his pectoral fins, lifting and lowering the beast as wing-flaps lift and lower an airplane. His eyes are unblinking and without dimension — flat, black disks, buttons of onyx. His nose is long and pointed, piercing the gloom like a warhead. His skin is tough and unyielding like canvas stretched over steel, but it is sensitive enough to pick up faint vibrations miles away — super-sonar. His mouth is closed and fixed in a humorless grin, concealing the eating machine within eight rows of long, hollow teeth arranged helter-skelter in each rank like thorns on a dead rose.

The image is one of lifeless menace — a kind of mechanical extension of a mad scientist’s vision. A bionic killer of the deep. And when he senses prey — through vibration or smell — he explodes into action with a single spasm of his tail and bears down on his victim like a freight train. Often the victim is large, for the mako burns fuel like a blast furnace. Marlin, broadbill swordfish, tuna, are favored targets. The first hit is almost always the tail — one crunch of its compactor-like jaws and the tail is either severed or hangs by a tendril. Then. with his prey spinning aimlessly, the mako comes back to hit its underside in a cloud of blood as a thin, protective membrane slides over his eyes, a touch of engineering genius from the drawing boards of evolution. As the vanquished fish descends through the darkness, other sharks arrive to feast on its remains while the mako, its belly full, circles slowly upward, seeking the surface to bask in the sun.

Related: Great White Shark Tales from Cape Cod’s Charter Boat Captains

It seems ironic that in all the uncharted regions of its dark domain, the mako faces his only real danger on the ocean’s surface. Ironic to you perhaps, but not to the mako. For he has visited that place beyond the bright water more than once — and never has it been a happy experience.

Always the visits are accidental: while chasing a school of baitfish too close to the light, swimming blindly at top speed in an aggravated effort to flush sea lice from his gills, or, once worst of all, when something caught in his mouth. For the first time in his life, the great shark couldn’t swim freely and, panic-stricken, bolted clear of his world and there was only emptiness, and his tail and pectoral fins were helpless in the void. But to swim just inches beneath the void, to feel the warmth of its light, to be refreshed by the oxygen rich water, and to feast endlessly on the vast schools of mackerel — it all seemed worth the risk.

Lobstermen Kim and David Lester watched July 28, 1977, break blue and balmy off the eastern tip of Long Island. They instantly agreed that this was The Day of The Swordfish. So they dropped their pots, climbed aboard their 37-foot workboat Theresa, and headed south-southeast off Montauk Point. They had waited all summer. Now they would shrug off their professional concern over a mediocre lobster season and enjoy their busman’s holiday at sea. While Kim guided the Theresa through a welter of charterboats trolling the shoreline for blues and stripers, the brothers sat on the flying bridge, joking and trading stories and scanning the flat empty sea for the black dorsal fin of basking swordfish.

About 12 miles out over the great Continental Shelf where swordfish and other sea giants play in the summer, they spotted a dorsal fin cutting slowly through the bright surface about 1,000 feet to starboard. While David padded toward the bow where two harpoons lay ready, Kim throttled down and the Theresa slowly, almost silently, moved in behind the cruising fin.

As the boat closed in, Kim be came apprehensive. Something was wrong. Then he remembered: Where was the tail? You always see the sickle-shaped tail of a swordfish. It must be a shark, he reasoned. But what kind of shark? Obviously, the dorsal was too big for anything but a great white. But before he could say anything, his 19-year-old brother had raised the harpoon high and sent the detachable head deep into the fish’s back just aft of the dorsal.

Instantly the fin disappeared into the sea, its passage marked by the half-inch line attached to the ring in the harpon iron. With the line jumping crazily from the wooden box in which 1,000 yards had been coiled neatly, the beast barreled toward the bottom on a slight angle out to sea. Then it stopped, providing Kim with enough slack to loop the line once around the loggerhead. Then the fish came straight back toward the boat while Kim hauled desperately to retrieve the line. Up, up, up it came — bursting into the still summer day. The steely blue, flesh-and-blood missile vaulted 10, 15, then 20 feet against the sky, then crashed home on its side in a shimmering explosion. The dumbstruck brothers watched the depression it made in the flat sea, watched immobile as the singing line followed the fish’s descent, and Kim knew it was not a great white. It was a mako, one of the largest anyone had ever seen.

Six hours later, Kim and David watched their prize hauled tail-first to the crossbeam of the scales back at Darenberg’s dock in Montauk. It weighed 1,250 pounds, had a 7½ foot girth and, later that night, its belly was slit open and a 150-pound swordfish slid out as easily as a trout from a creel. It was the strangest double header of this, maybe any, season.

Like all its 250 known relatives, the mako has been maligned as a creature of the lowest order to be wiped out like vermin. Human fear rules such a view. But for those able to see beyond their fear, the mako becomes an animal of extraordinary grace, power, and beauty, a miracle of natural design in which every fin, muscle, organ, and piece of cartilage has been modified by 100 million years of evolutionary refinement. Like the peregrine falcon, the cheetah, and the red ant, the mako is the quintessence of the species. The prince of sharks.

But splendid creature that it is, the mako has only recently been recognized by serious anglers. Zane Grey, who during the 30’s traveled the oceans of the world in search of record marlin and tuna, was perhaps the first angler to appreciate the mako’s singular fighting abilities. So much so that Grey spent three seasons off the North Island of New Zealand catching 70 makos, the largest weighing 580 pounds.

“The mako,” wrote Grey, “undoubtedly ranks with the marlin in acrobatics and with the swordfish in strength and wariness before a baited hook.”

Due partly to Grey’s writings, the mako was eventually elected to the inner circle of saltwater’s elite gamesters — marlin, swordfish, tuna, sailfish, tarpon — by the International Game Fish Association. Today the world’s all-tackle record stands at 1,061 pounds, caught off Mayor Island, New Zealand in 1970. But since Peter Benchley’s “Jaws” clamped onto the national consciousness, sharks have become prime targets for legions of anglers. And as a result, more makos have been caught in the past three years than in all previous years combined. Just last July 18, for example, James George of Paterson, New Jersey, caught a 1,039-pounder, establishing a new U.S. record.

“She jumped 35 feet out of the water,” claims George, who battled the female for five hours. “Twice she rammed our boat. It was the most exciting but scary time of my life.”

Though Zane Grey first reviewed the mako’s convincing performances as a gamefish, entrepreneur Frank Mundus deserves for giving it its first real break in show business. Never in all the theatres of the oceans has there been a more colorful act than Mundus and the Mako. In the early 1950’s, Mundus arrived unannounced at Montauk in his 37-foot Cricket I, rented a slip in the harbor, and set up shop among the sleek chariots of some of the most famous and competitive big-game skippers on the East Coast.

Predictably, the local reception was cool, if not hostile. But when Mundus revealed that he would fish exclusively for sharks, there was an immediate thaw. To the local big-game purists, sharks were the stray dogs of the sea, and if Mundus was willing to control the population he was accepted as an eccentric asset to the community. Promptly dubbed “the shark man,” Mundus was made to feel welcome in Montauk for as long as he wished to stay.

Mundus stayed and prospered, for he knew something that escaped his colleagues. He knew that for every seasoned or aspiring marlin or tuna angler there were literally dozens of less-selective types who would pay a premium for the thrill of catching a denizen of the deep. He knew, too, that there was a world full of people to whom adventure came only in a book, or a movie, city people who had never been in a boat much less aboard the Cricket I, battling a shark beyond the sight of land in the world’s truest wilderness. Perhaps most important, Mundus knew that there were infinitely more sharks off Montauk Point in the summer than all the tuna, marlin, and swordfish combined. Where his colleagues could only promise a strong effort, Mundus guaranteed success.

With a flair for theatrics equal to P.T. Barnum, Mundus provided his clients with an experience at sea they would not soon forget. He was Bligh. Ahab, and Quint rolled into one bizarre character. But underneath it all there was always Mundus, the actor, winking reassuringly at his audience as if to say, “It’s all a bloody game. Enjoy it.”

Game? It was more like a circus: Mundus painting his toes ( one red, one green) to tell left from right; whipping on his surgeon’s costume before “operating” on a freshly caught shark; exploding cherry bombs in the ocean (“Sharks like the noise”); dispatching unruly battlers (sharks, that is) at boatside with a .22 caliber rifle. Mundus’s repertoire was endless, and he had a prop or costume for every conceivable eventuality.

If he could act the clown, he could also be deadly serious, especially about his favorite subject. Of all the species of shark that frequent the waters off Montauk, Mundus is partial to the great white and the mako. On June 5, 1964, Mundus harpooned and subdued the largest white shark on record — 4,500 pounds.

“I’ve seen ‘em bigger than that one,” he once told me. “Benchley’s white was 25 feet in ‘Jaws.’ Experts say that’s impossible. But I’ve seen ’em over 20 feet, so I’ve got to believe that somewhere in the world there’s one that fits Benchley’s imagination.”

What captures Mundus’s imagination, however, is the white shark’s close cousin — the mako. “For explosive combat tactics and leaping ability,” says Mundus through writer Bill Wisner in their definitive book “Sportsfishing for Sharks,” “they (makos) have few peers. What’s more, they do the damndest things when they’re brought to boat.”

For example:

“As the mako zoomed through the air on a parabolic trajectory he came down squarely across one of the two anglers’ rods. Down the rod slid the shark’s bulk, shearing off rod guides as it went. The startled fisherman, seeing a few hundred pounds of mako about to be deposited in his lap, had the presence of mind to try to get the hell out of there. He jumped out of the fishing chair, going over and backward, and landed on his head on deck, almost breaking his neck. The mako slid into the cockpit and promptly took over. The first thing he did was smash a rod butt.

Pandemonium broke loose. The shark went berserk. Bouncing and twisting violently, he slammed his way from gunnel to gunnel. He smashed fishing chairs; he sent chum cans flying to spew their contents all over the place; and with a passing swipe he tore a rod holder off a coaming. All hands beat a hasty re treat to the cabin and barricaded themselves behind the companionway door. Seconds later the mako crashed against the door, knocked its knob out by the roots.”

One warm September day in 1974, Peter Benchly and l went fishing aboard the Cricket II with an ABC film crew to record for posterity the meeting of the two most colorful shark men still alive to tell about it. We headed out into the Atlantic under the cover of pre-dawn, the three of us sitting in the flying bridge. After a while, I asked Mundus if he’d read “Jaws.”

“Nope,” he said. “Why not?”

Looking dead ahead, Mundus was plainly arranging his answer.

“Look,” he said. “‘Jaws’ is a novel, right?”

“Yep.”

“And a novel is fiction, right?”

“Yep.”

“And fiction . . . is … bullcrap!”

Benchley and I still laugh about Mundus’s dead-center-perfect answer. But actually, why should Frank have read “Jaws”? A man who has been living an adventure with sharks all his life certainly doesn’t need to be fulfilled by reading a novel about them. Quint fought a 25-foot white shark in a book. Frank Mundus fought a 17-footer, the largest known to man, on the open ocean. Next to Mundus, Quint is a pale pretender.

Anyway, later that day, after we’d caught six blue sharks, Benchley tied into something very fast, very strong. Though it rolled and breached several times, we never got a good look at it. I said mako. Mundus didn’t answer. Benchley merely grunted against the throbbing force at the other end of the line.

Read Next: Everything That’s Wrong with the ‘Jaws’ Fight Scene

Finally, after 45 minutes, we sank the gaff into a 252-pound broadbill swordfish. Mundus looked at me and said, “That’s what I thought. Too slow for a mako.”

That night back at Montauk, we slit open its belly.

No mako.

Read the full article here