Like he always did, Jake came when I called, tail wagging and head lifted to the next command. When he got close enough, I shot him with my deer rifle while my dad killed the other two dogs.

This is not how I expected that April morning — or frankly any other morning in my life — to turn out. I was home for the weekend from my freshman year in college, helping my parents sort and brand calves on our north Missouri farm. But there was a problem, my mom had told me a couple weeks earlier over the tinny dorm telephone in those days before cell phones.

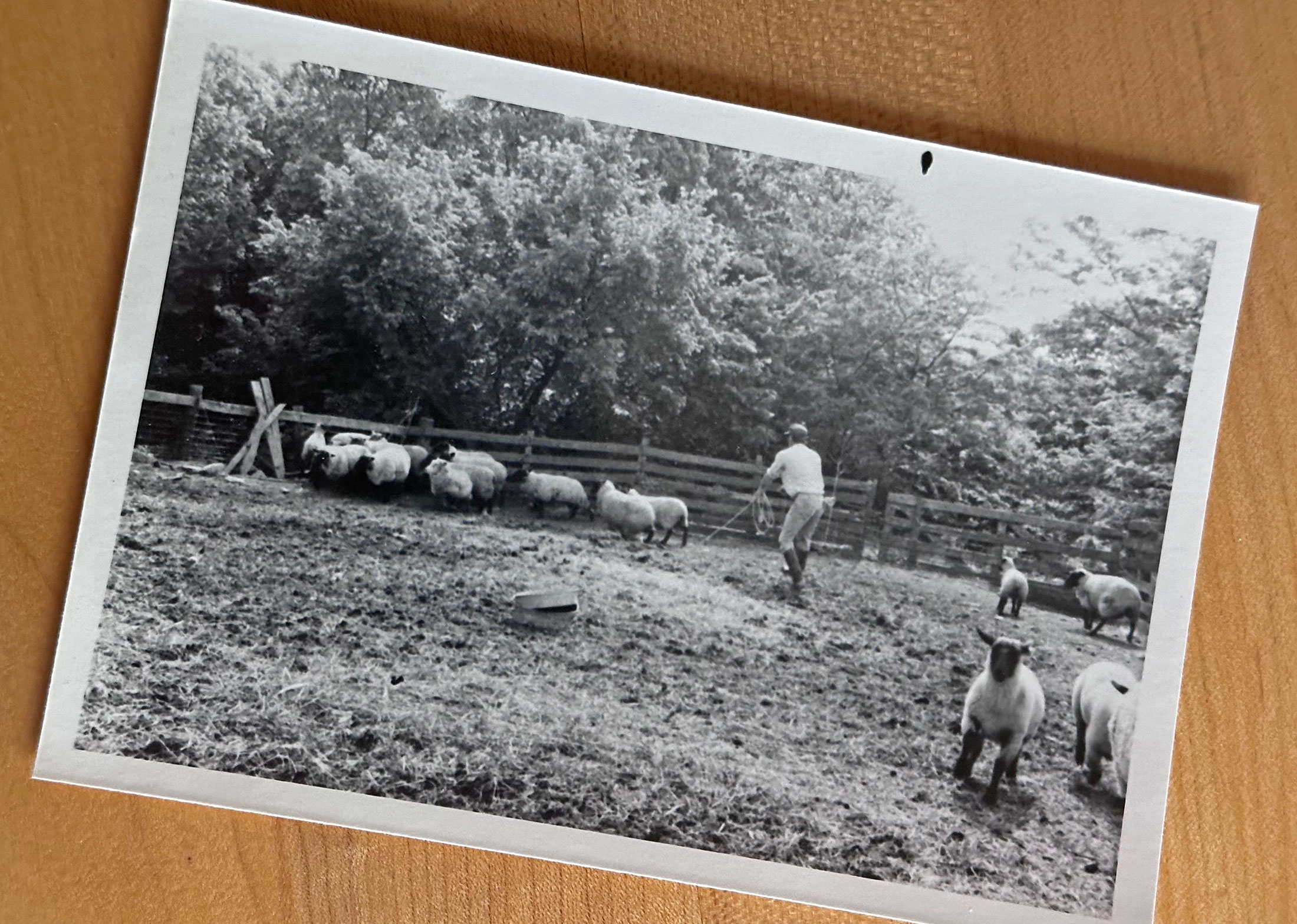

Something was killing our lambs, she said, in the daytime in the pasture out in front of the house while she was away at work. But the predator didn’t eat the lambs, only ripped open their abdomens and left them to die. I was as puzzled as she was, and as bad as I felt for the sheep, I felt worse for my mom that this was happening on her watch.

She was holding down the farm by herself, while also teaching high school English in a town down the road. My dad had taken a job at a university five hours away and came home on weekends. This was the mid 1980s, a dark time for small farmers across the Midwest who were squeezed by high interest rates and low commodity prices. The only way we could keep our place was if my folks got off-farm jobs. Attending a high-priced college up in Iowa, I felt guilty that I couldn’t be more helpful.

At least my mom had Jake to keep her company. I had received Jake, a lively 12-week-old border collie, as a high school graduation present, and if you take anything from this story it is to never gift a high school graduate with a puppy. I was headed to college and taking Jake with me was out of the question. So my parents inherited a dog, and they made the best of it until my dad left for his new job.

Jake was a good boy. I had spent the summer before college training him in the basics, and like most border collies, he was eager to work. He was especially adept at gathering cattle and sheep, but he’d also herd cats and even humans. Fall arrived and I left for college. My folks, figuring Jake needed company, acquired a pair of shelter dogs. When they told me that, I recalled the words of a neighbor: “One dog is just a dog. Two is a pair. Three is a pack, and you can never know what a pack will do.”

I had my hunches that the lamb-killers were Jake’s pack-mates, and until that April morning I was hoping for any other explanation. But sitting at the kitchen table in the farmhouse where I grew up, I watched through the window as Jake and his companions ran into the pasture, cut out a lamb, and killed it. My parents hadn’t witnessed the episode, and it briefly occurred to me that if I could distract them from the carnage, I might save Jake.

But I couldn’t. As I told my dad what I had witnessed, I already knew what the next words out of his mouth would be.

“Get your rifle. Then call your dog.”

The Governor Shoots Her Dog

My memory of this morning 30 years ago was thrust into the present this week, as news broke that South Dakota’s governor, Kristi Noem, killed her dog a couple decades ago in a startlingly congruent experience to my own.

Noem has been pilloried for telling the world of her decision to shoot her dog, a wirehair pointer named Cricket, in a book that will be published next month. Some pundits predict that her disclosure amounts to “political suicide” that will disqualify her from consideration as a vice president pick for presumptive Republican nominee and former president Donald Trump.

In her book, Noem describes “hating” Cricket, something I can’t begin to understand. But I do understand her conclusion that 14-month-old Cricket was “untrainable” and “worthless as a hunting dog” after a disastrous pheasant hunting session. But it was when Cricket attacked a neighbor’s chickens, killing several “like a trained assassin” that Noem concluded no corrective action was going to work.

I recall pleading uselessly with my dad. As we gathered our guns, I conceded that we should kill the other two dogs, but maybe we could give Jake to a neighbor, or I could find someone at my college to take him.

“So you’d give a known livestock-killer to somebody else to deal with?” my dad said. I recalled my dad killing a stray dog when I was very young that had stampeded our cows through fences, and knew he had little tolerance for a calf- or lamb-killer. But, looking back on it, I think in this one moment all the anxiety and uncertainty over our farm and our current economic situation came to the surface. Instead of thinking through some alternative, my dad defaulted to an ancient law that demanded a livestock-killing dog must die.

As much as I realized Jake was involved, I also knew that if it hadn’t been for those two stray dogs, he never would have turned into a lamb-killer. I also knew that if anyone was going to kill Jake, it had to be me.

I felt — and still feel, 30 years later — a surge of guilt that I let Jake down, by not being present for his formative months. I wonder if Noem similarly gave up on Cricket, or wasn’t attentive to her particular training requirements, allowing her to turn rogue. I’ll observe it’s rarely the dog’s fault they turn out the way they do, but rather ours.

My dad, and presumably Noem, who grew up on her parents’ South Dakota pheasant-hunting preserve, descend from an unsentimental population of people who recognize that domestic animals — whether a beef cow or a family dog — exist mainly to serve. That is a foreign concept to many American pet owners, who indulge all sorts of bad behavior from their animals but who would never think of disciplining them harshly, let alone ending their lives.

I’ve inherited only a small measure of this cold-eyed practicality. In a pact I made with my best friends a decade ago, we each agreed to kill each other’s hunting dogs when the time came and their health declined so severely that they needed to be put down.

We each recognized that we might not be able to pull the trigger on our own dogs, but we also acknowledged that taking our beloved dogs to a veterinarian for the final act of mercy is often, especially in rural areas like mine, a sterile, loveless execution. How much better to spend the last happy moments in the field, with a snout full of scent and light all around, before a trusted companion initiates an endless retrieve.

Difficult, Messy, and Ugly Things

Even this sentimentality would have been lost on our grandparents and every generation before them. The truth is that the death of our pets has become a sanitized, ritualistic exercise that in many cases is more emotionally impactful than the death of the humans in our lives. Our ancestors would have considered this perverse, and many rural Americans still do, not because they cherish their dogs or horses or pedigreed bulls less, but because they experience the cycles of life and death and gain and loss more frequently, closely, and casually than those of us for whom the loss of a family dog may happen only twice or thrice, and is described euphemistically as putting our pets “to sleep.”

It’s also worth noting that many states’ animal cruelty laws, which outlaw wanton violence against domestic animals, allow for the killing of dogs that are harassing livestock, and in some states, wildlife.

After Noem shot Cricket she reportedly threw his body into a gravel pit, an especially unsentimental end that has heaped even more derision on her. Compounding the wince-factor, Noem dropped Cricket’s body on top of an unnamed goat, which she had earlier shot after the uncastrated billy took to chasing Noem’s kids, knocking them to the ground and generally acting like a rut-aggressed male.

As much as I can relate to Noem’s instincts in those moments, I can’t forgive what appears to be her political intentions in bringing them to our attention now. Her book, “No Going Back: The Truth on What’s Wrong with Politics and How We Move America Forward,” is calibrated to burnish her political image and give her national media attention as Trump decides on a running mate. Or, as some expect, she makes a run for the executive vice-presidency of the National Rifle Association, a position recently vacated by shamed Wayne LaPierre.

Presumably, Noem’s inclusion of Cricket and his fate in the book is intended to illustrate her point that sometimes Americans must do “difficult, messy and ugly” things in order to move forward.

Maybe Noem has moved on from Cricket. As for me, after the rifle shots and then the branding and calf sorting of that April day, I spent a long time alone digging a grave for Jake on the edge of the woods. In the years since, we ended up selling our family farm, and I’ve had other dogs and other places, but every year around this time I wonder if his collar is still underneath the rock that I rolled over that turned Missouri dirt.

And I still think of Jake as a good boy.

Read the full article here