THIS STORY REALLY STARTS a good many years ago. I was living in northern Arizona then, in the midst of as good mule-deer country as can be found in the United States. It was a case of being embarrassed by riches, since there were so many hunting spots that I could never get around to all of them. Some were famous all over Arizona. Others, just as good, were celebrated only locally.

One of these is the Slate Mountain section—an area of high volcanic peaks, cinder cones, wide parks knee-high with rich yellow gramma grass. Turkeys range on the mountain slopes, antelope wheel and maneuver, flash their white rump patches in the parks. But primarily it is mule-deer country. The animals feed clear up into thick fir and spruce of the high peaks in the summer, then drift gradually down before the chill of approaching autumn. Their winter range around Slate Mountain is thinly timbered, but it abounds in canyons where they can get out of the wind, and it has plenty of winter feed in the shape of dwarf juniper and cliff rose—or buck brush, as the natives call it.

Almost from the first, I was aware of Slate Mountain’s local fame as buck country, but I always got a buck somewhere else before I got around to hunting there. It took some plain and fancy stories to draw me in there-and I got them. A cowboy told me how he had ridden into a little canyon one windy day and jumped out a bunch of fifteen or twenty big bucks. A woodcutter told me how he saw deer there every time he went in. The supervisor of the national forest told me a dozen tales calculated to make any hunter’s mouth water. And through all these stories, an account of one particular big buck ran like a theme song.

One hunter who had seen him in gray dawn thought for a moment that he was an elk and did not shoot until too late. Others had grown so excited at a glimpse of him that buck fever made their bullets go wild.

The upshot was that I decided to investigate the section where this big buck ran. It was the first day of the 1933 season, and as I drove out there I felt a bit foolish. In the first place, the stories of the Slate Mountain area sounded too good to be true. In the second, hunting for one particular buck is usually about like searching for the traditional needle in the traditional haystack.

Well, my first Slate Mountain hunt was pretty uneventful—except that I got lost and that I’m convinced I saw the patriarch himself. Alone, I pulled up into a little canyon, changed to hobnails, took a quart canteen, a candy bar, and my Springfield, and set out. I circled the mountain high up where most of the canyons headed, edging along on slippery pine needles. I saw lots of deer sign that day and also some deer, mostly does and fawns and a few small bucks. To the north, over tawny grasslands spotted with purple patches of juniper, I could see the scarlet gash of the Grand Canyon overlined with the blue of the famous Kaibab. To the northeast lay the pink and mauve and yellow emptiness of the Painted Desert.

Dusk was gathering when I started down the mountain. I had been in sunshine, 1,500 feet above the plain, but as I went down it grew swiftly dark, and when I came out of the canyon I had chosen I found it wasn’t the one in which I had parked the car. I have never been inside a cow, but if it is darker there it is plenty dark. I could see my hand before my face, but that is about all. Further, I was in country strewn with volcanic bowlders and cut with draws that dropped straight for fifteen or twenty feet.

Afterwards, when my friends twitted me about the experience, I maintained that I was not lost. It was the car that was lost. Dimly in the starlight I could see familiar mountain peaks bulking black against the horizon. I knew within a quarter of a mile where I was, but I could have passed within ten feet of my car without seeing it. So I built a fire on the lee side of a dead pine, made myself a bed of pine needles, and caught some sleep.

When the first gray of dawn came, I picked up my rifle and went back to the car, which I located without trouble. I was hungry and I was thirsty, so I opened an iron ration and took a drink from the canteen.

Then I looked up—and there was the biggest buck I’d ever seen.

Actually he looked as big as a horse, and his antlers were so enormous that they showed plainly in spite of the fact that he was more than 200 yards away and in the gloom of timber. I dived for my rifle, but the buck disappeared just as I threw off the safety. I spent an hour that morning trying to find him, but his big tracks showed that he was long gone. So I went back to town, and to coffee and scrambled eggs and the reproaches of a frightened wife who didn’t like her husband to stay out all night without telling her about it in advance.

The memory of that enormous buck haunted me, and two days later my wife and I were back there with food and bed rolls and hope in our hearts. As we drove through a big open park east of Slate Mountain we saw a herd of forty or fifty antelope, so when my wife said calmly, “A big buck just ran into that draw!” I thought she meant a buck antelope and paid no attention. Afterwards she said she thought it strange that I showed so little interest, but being a well-trained wife she did not comment at the time. We drove on up to the slope of a cinder cone, stopped, and got out our rifles. Then I happened to look up, and there, about 400 yards away, were three deer trotting through the junipers, gray against the red cinders.

Eleanor, who is an optimist as well as a good shot, went into action. They were bucks, I saw as soon as I put the glasses on them, but they disappeared into thick juniper unhit as far as I could tell. Then something drew my attention to the saddle between two cones, and I saw a sight I had never seen before and have never seen since—a herd of at least twenty big bucks, all on a dead run. They were in sight but an instant, and with all those antlers against the horizon they looked like motion pictures I have seen of a herd of migrating caribou.

Figuring that they would skirt the cinder cone to our left, I decided to run over the top and catch them as they crossed an open park to the west. The cone was about 500 feet high, and when I topped out I was winded. Eleanor had fallen somewhere by the wayside.

Cautiously I circled; and when I had gone about fifty yards, three huge bucks came bouncing out, great brown antlers laid back against gray hides. The biggest was truly a monster, and I cut loose at him. The three disappeared into a clump of mixed oak, pine, cliff rose, and juniper at the foot of the hill, just as I got off what I thought was my best shot. Only two came out, and when I got down there I found my huge buck, hit three times from my six-shot fusillade once in the left ham, once in the abdomen, and once, alas, right through the ear.

For a moment I thought I’d got the patriarch himself. When I looked across the open park to the next hill slope, however, I began to moan. The whole hill was alive with deer, but I had eyes only for one—an enormous buck that looked as big as a medium-sized elk as he stood there. I knew then that I might have got one of the patriarch’s sons but I surely hadn’t got the patriarch.

I WISHED my wife were there to take a shot at him, but she wasn’t, and by the time she found me the whole herd had melted into the timber. Leaving her to see if she couldn’t hunt one of them up, I cut across the cone to bring the car around from where we’d left it half an hour before. A few yards from where the deer she had shot at had disappeared, I heard the brush crack. When I investigated, I found a buck with both hind legs broken. I would have sworn Eleanor hadn’t touched one, but there he was. So we had our bucks, both of us, after as short, as dramatic, and as astonishingly lucky a hunt as I have ever been on.

As often happens, the head of the head of the buck I got looked better when it was on the move than it did in the hand. But, for Arizona mule deer anyway, the animal was a whopper. He weighed 176 with his head and neck off, his hide off, and half of the left ham cut away. I didn’t probably the heaviest buck I have ever shot.

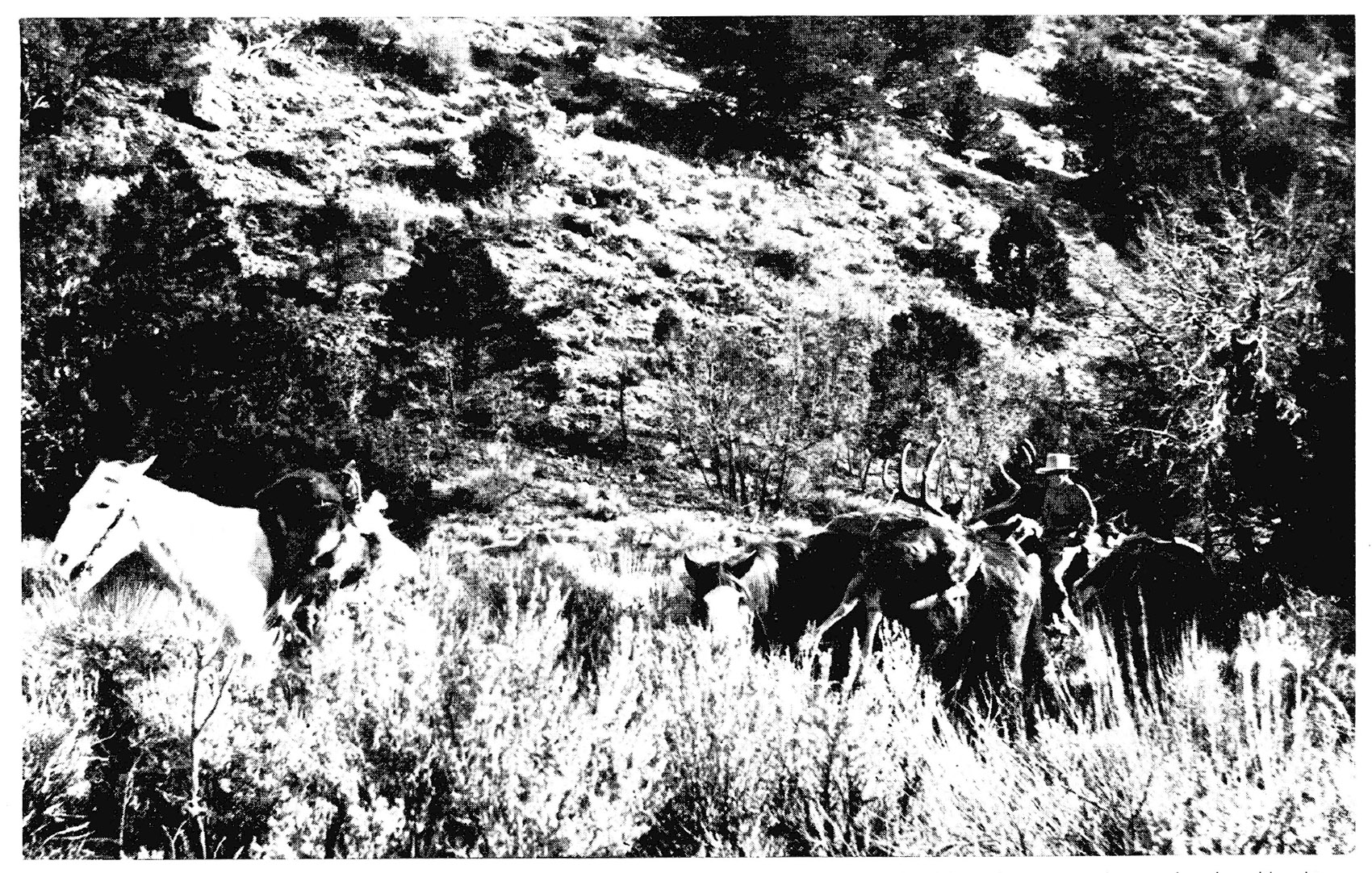

Fate moved me 300 miles away into southern Arizona the next year, but I still remembered that great patriarch I’d left behind. So the end of the season found me once more in the Slate Mountain country. With me were two University of Arizona professors, Waldo Waltz and Neil Houghton. Both were authorities on political science, but their education had been neglected, as neither had shot a buck. Our guide and horse wrangler was one Slim, a local vaquero and an old friend of mine.

WE pulled into our rendezvous with Slim late one night after the long drive from Tucson. Neil and Waldo were both pop-eyed with anticipation, as I had been feeding them on my best Slate Mountain stories; but when we met Slim by the glow of his camp fire, he tossed a little cold water on our enthusiasm.

he wasn’t so big as

the chap I was after.” Outdoor Life

“It ain’t snowed a mite yet,” he told us, “and them dad-blamed deer is scattered from hell to breakfast. Most of the big bucks is still high up.” Then he added piously, “I sure been a-hopin’ for snow since I heard you boys was a-comin’.” He glanced up at the sky then, but it was blue-black, perfectly clear, blazing with ten thousand stars.

“Has anyone potted that big old buck since I was up here?” I asked.

“Not that I’ve heard of,” he reassured me, “but that ain’t no sign somebody ain’t knocked him over for meat.” Slim, as I may have hinted before, is not exactly an optimist.

However, the Slate Mountain patriarch, though he was destined to remain only a name during the trip, did lead us to good hunting; for we saw our first deer within a quarter of a mile of camp the next morning. We were riding along the edge of a wide, fairly shallow canyon when we saw a movement in some cedars. Deer, all right; but at first we thought they were does and fawns. Neil dismounted and pulled his borrowed .30/30 out of the scabbard just in case. When they ran presently, we saw one was a buck, a small one; and on Neil’s third shot it went down-a two-year-old, three-pointer that had still been hanging around the does. The professor had done his stuff.

We split then. Waldo and Slim headed one way which Neil and I rode for the high country, where the bigger bucks ought to be hanging out. We hadn’t gone more than a mile when we heard the heavy report of a .30/06. Five shots, more or less regularly spaced, then a sixth shot.

“Sounds as though Waldo has connected,” I told Neil. “Let’s ride back and see what luck he had.”

A few minutes later, on the opposite side of a hill, we found Waldo and Slim bending over a buck, another three pointer that would dress at about 130 pounds. Waldo had hit it with his third and fifth shots. It went down, and a bullet in the neck had finished it when they came up. We ate an early lunch then and planned the balance of the day’s campaign. Slim and Waldo would pack the two bucks back to camp while Neil and I pursued the chance of getting a shot at the patriarch himself.

It was so dark when we returned that night that we had to give the horses their heads to make it possible for us to find camp. We had covered at least twenty miles and had hunted in rough country more than 8,000 feet in elevation. We had seen bucks, too, but nothing to make a head-hunter’s mouth water, so we passed them up.

The second day was much like the first. We spared neither ourselves nor the horses, and saw our usual quota of does, fawns, and young bucks, but I did not fire a shot.

The last day of the hunt started out even worse. During the morning it clouded up and rained a little. We saw not a single deer, nor even a single track made since the rain. If deer were there, they were bedded and not moving. By noon the gloom was thick enough to cut with a knife. Slim and I swapped halfhearted stories about the old patriarch his enormous head, his great weight. By three o’clock we had all become reconciled to our fate. The next morning we’d have to leave with only two bucks, neither of which had a good head. We were twelve or fifteen miles from camp, and it was time to turn back. For several minutes we sat on the edge of a canyon, smoked cigarettes, and cursed the weather, the deer, and our luck.

I stood up, ground my cigarette under my heel, and prepared to mount. Then, almost 300 yards a way, down toward the bottom of the canyon, I saw something move-something that became a great buck going out from behind a cedar in long downhill bounds. He had evidently been lying there, conscious of our presence, hoping we would pass him by, but getting more and more nervous. When I got up he couldn’t stand it any longer and ran.

I got off my first shot before the others saw him. It was a miss, behind and below. My second kicked up dust just over his back, and my third rolled him in foot-high sage.

NOW that I had him down I began to shake. He was an enormous buck, no doubt of it. He might even be the patriarch himself, and the thought was too much for my none too stable nerves. When I had reloaded I started down the hill toward the spot where he had fallen. At a little over 100 yards he came out, one front leg dangling but making good time nevertheless. I missed with a too hasty snapshot, He was going up the other side of the hill now. In a moment he would be behind the cedars. So I took a deep breath, sat down, and held on his brisket. He came down at the shot—down like a ton of brick—and I knew he was mine.

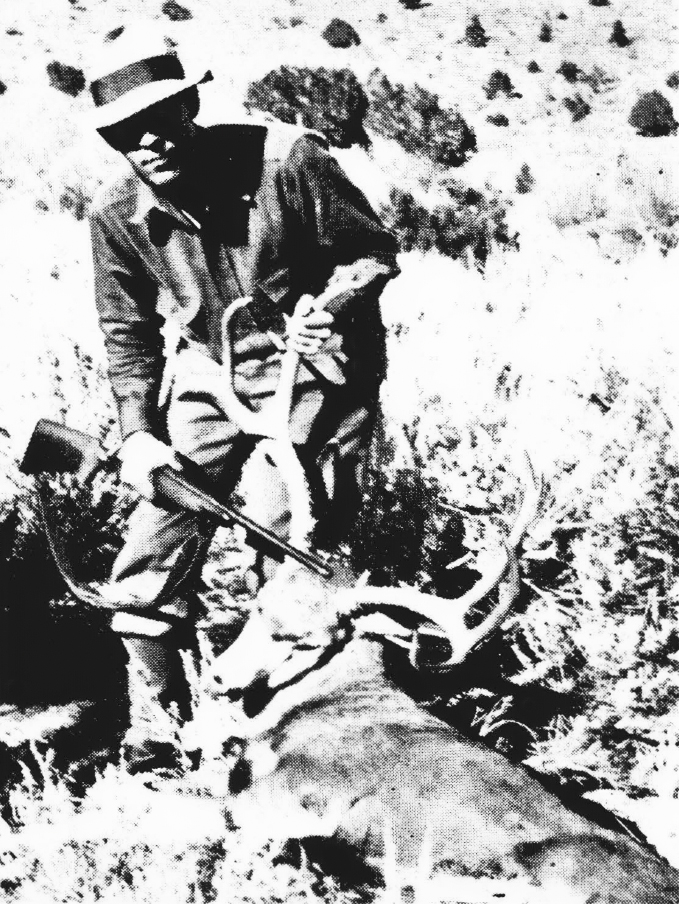

A minute later I stood over him.

“He’s the big ‘un, the big ‘un himself,” Slim was shouting. Surely he was a magnificent creature: fat, heavy, lithe, with the wide, symmetrical head the collector dreams about. An Easterner would call him a 13-pointer, but in the West he would be a 7-pointer, as he had six points on one side and seven on the other.

“You shore got him!” Slim kept saying.

“That’s the dad-blamedest biggest old buck I’ve ever seen.”

But the longer I looked at that buck the surer I was that he was not the patriarch. His teeth showed him fully mature but not old, in spite of the record- class head he carried. “It’s one of his kids, Slim,” I said finally. “It isn’t the old one.”

“Well, if I got a buck like that,” Neil interrupted, “I’d be darned if I’d kick about him.”

I still am proud of that head, as it is one of the three or four largest that I have ever taken, but I am now certain that on that red-letter day back in 1934 I didn’t get the patriarch. For I saw him again last year, and that is when this story properly ends.

My wife and I were returning from the Kaibab with two bucks, when we saw a truck turning into the highway from the direction of Slate Mountain. In it were two bucks, and one of them was the biggest I have ever seen dead. I signaled for the driver to stop.

“You surely have a big buck there! Where did you get him?” I asked, knowing the answer before I heard it

“Slate Mountain country.”

I EXAMINED the great buck’s teeth. He was very old. “I’m sort of a semi-pro biologist, particularly interested in game,” I told the hunters, “and I’d surely appreciate it if you’d meet me in Flagstaff so I can weigh and measure that buck. He’s the largest I have ever seen, and he has one of the best heads.”

They promised, but they didn’t show up. Why, I do not know. Possibly they were hunting illegally. Surely they must have had guilty consciences of some sort.

And that, I am convinced, was the end of the Slate Mountain patriarch. When he was killed he must have been ten or twelve years old, as when I first saw him he was fully mature and already had a reputation. I still regret that I didn’t measure that head on the spot, as I had a tape with me. My guess is that it would have shown a spread of close to 45 inches and a main beam of 32 or 33.

His weight? Well, I’m a conservative and fairly accurate weight guesser. I’ll admit that the biggest Southwestern mule deer I ever saw on the scales went 240 pounds and the largest I have any authentic record of went 261. Admitting all this, I am nevertheless going to stick my neck out and guess the Slate Mountain patriarch at close to 400, dressed.

It is too bad that the old fellow couldn’t have fallen to a head-hunter, so those magnificent antlers of his could have been mounted. Yet at that he has achieved immortality of a sort, as he’ll long live in the hunters’ tales of northern Arizona. Furthermore, he helped populate the Slate Mountain country with a magnificent breed of bucks, and his descendants will range there, I hope, forever. I’ll always be grateful to him, as he lured me into country which yielded me one of the most prized trophies I have.

This story originally ran in the July 1939 issue of Outdoor Life as “The Slate Mountain Patriarch.”

Read the full article here