This story, “Ordeal and Death,” appeared in the July 1968 issue of Outdoor Life.

WHEN THE SUN went down last September 20 in the remote wilderness of northern Quebec, Don Barnard and I didn’t have the least suspicion we were hopelessly lost. If some body had told me that this was the beginning of an ordeal almost too terrible to describe, I would have thought he was crazy.

Four of us had been flown to an unnamed lake that morning. We’d set up our tent camp, then scheduled an afternoon of scouting for caribou. The sky was a deep blue and the temperature was in the 70’s when we paired off and parted. Don and I waved to our companions, then Don yelled, “See you in a few hours.”

Those were fateful words. They were the last words Don Barnard ever spoke to Terry Brandon and Bob Hammond. And it was the last time I would see Brandon and Hammond for 12 terrible days.

In the beginning, our hunt had all the earmarks of a great success. Don was the organizer, and he was well experienced in camping trips. He was an exceptionally strong man of 32 and was head of a family that includes five small children.

I’m 30, and my wife Rosanne and I have five children from two to 10 years old. I’m a dispatcher in the communications center of the Detroit, Michigan, Fire Department. Don worked for the same organization as a fire fighter.

Our companions, Terry and Bob, also live in Detroit. Terry is a construction steel worker. At 21, he’s married and the father of one young son. Bob is 35 and single, and he earns his living as a journey man pattern maker.

Don was the most experienced outdoorsman in our group. He’d made many big-game hunting trips to Wyoming and Idaho, and he’d become a nut on trophy hunting. Bob Hammond also is an experi encedtrophy hunter. He’s hunted in the Brooks Range of Alaska and has bagged fine caribou and Dall-sheep trophies, and he has spent many days in wilderness camps.

I’ve been hunting and fishing since I was 14. Though this was my first wide-ranging big-game hunt, I’d spent many weeks in Michigan deer camps. Terry Brandon’s experience compares with mine.

Don was an official measurer for the Boone and Crockett Club, and through his associations he’d heard about the fabulous hunting for Woodland caribou in Quebec. In November 1966, he phoned Ted Bennett, owner and operator of Laurentian Airlines, in Schefferville, Quebec.

“The bush up here is very remote,” Ted told him.

“The area supports hordes of Woodland caribou. There are no facilities or accommodations. When you go in there, you’re on your own. Shooting a trophy bull should be easy in late September. Let me know when you want to hunt, and I’ll fly you in and fly you out.”

Don set up our trip. Ted would fly us out of Schefferville to a campsite on a remote lake. We’d hunt on our own; then Ted would return late in the afternoon of the fifth day and fly us back to civilization.

We considered hiring a guide but discarded the idea because of the cost. Don owned a complete camping out fit. A 9 x 12 double-floor wall tent would be our home. We would cook on a three-burner gas stove, and a gas heater would keep us comfortable on cold nights. We also packed a gas lantern, cooking utensils, groceries, an ax, ropes, and knives. Each of us had a cold-weather sleeping bag and an air mattress.

We left Detroit at 6 a.m. on September 17, 1967. All our gear was packed in Don’s van truck. We drove straight through to St. Simeon, Quebec, 950 miles from Detroit via Toronto and Montreal.

The next afternoon we arrived at Sept Iles, Quebec. This little town marks the end of the road into the bush. Tuesday morning we were on a train rolling for Schefferville, 350 miles north.

Ted Bennett met us at the station 12 hours later. The next morning, Wednesday, September 20, we loaded our gear into Ted’s twin-engine float plane. By 8 o’clock we were in the air heading for our destination 75 miles to the northeast and 1,790 miles from Detroit. Below us, sunshine flooded a region that seemed to be more water than land.

An hour later we were taxiing toward our campsite on a rocky point in a little lake a mile wide by three miles long. We unloaded in a hurry, and by the time Ted’s silver plane was a vanishing dot in the blue sky we had the tent pitched.

We soon had our gear organized, firewood cut, and sandwiches made. We wolfed the sandwiches down and were ready to hunt.

The weather was warm and clear, so we dressed in light hunting clothes. There was no reason to pack lunches or foul-weather gear. We each pocketed a couple of chocolate bars and then walked away from camp.

I should add that we had no maps of the area, but this lack was not an oversight. We’d asked for maps in Schefferville and were told that none were available. The area we were hunting is only a few hundred miles from the northern line of tree growth, and most of it has never been accurately mapped.

Don and I took off on a northwesterly course. Ahead of us, a mile or so away, a high ridge jutted against the sky.

“Let’s climb that ridge,” Don suggested. “We can look around from up there and take compass readings on landmarks.”

The land in this area is all rock. There is no dirt or soil. The rolling ridges are topped with bare rock, and the ravines and lowlands are covered with spongy moss and bog. Pine, spruce, fir, tamarack, and blueberry bushes take root in the moss.

We topped the ridge in about an hour and looked down on a patchwork of blue and green. Lakes were everywhere. Fiddle Lake, the only named lake in the area, lay below us to the west.

I was admiring the scenery when Don said: “See ’em?

Seven of ’em. One good bull. Let’s stalk ’em.”

The caribou were half a mile away, but they weren’t going anyplace in particular. We followed them five miles and changed direction 10 times.

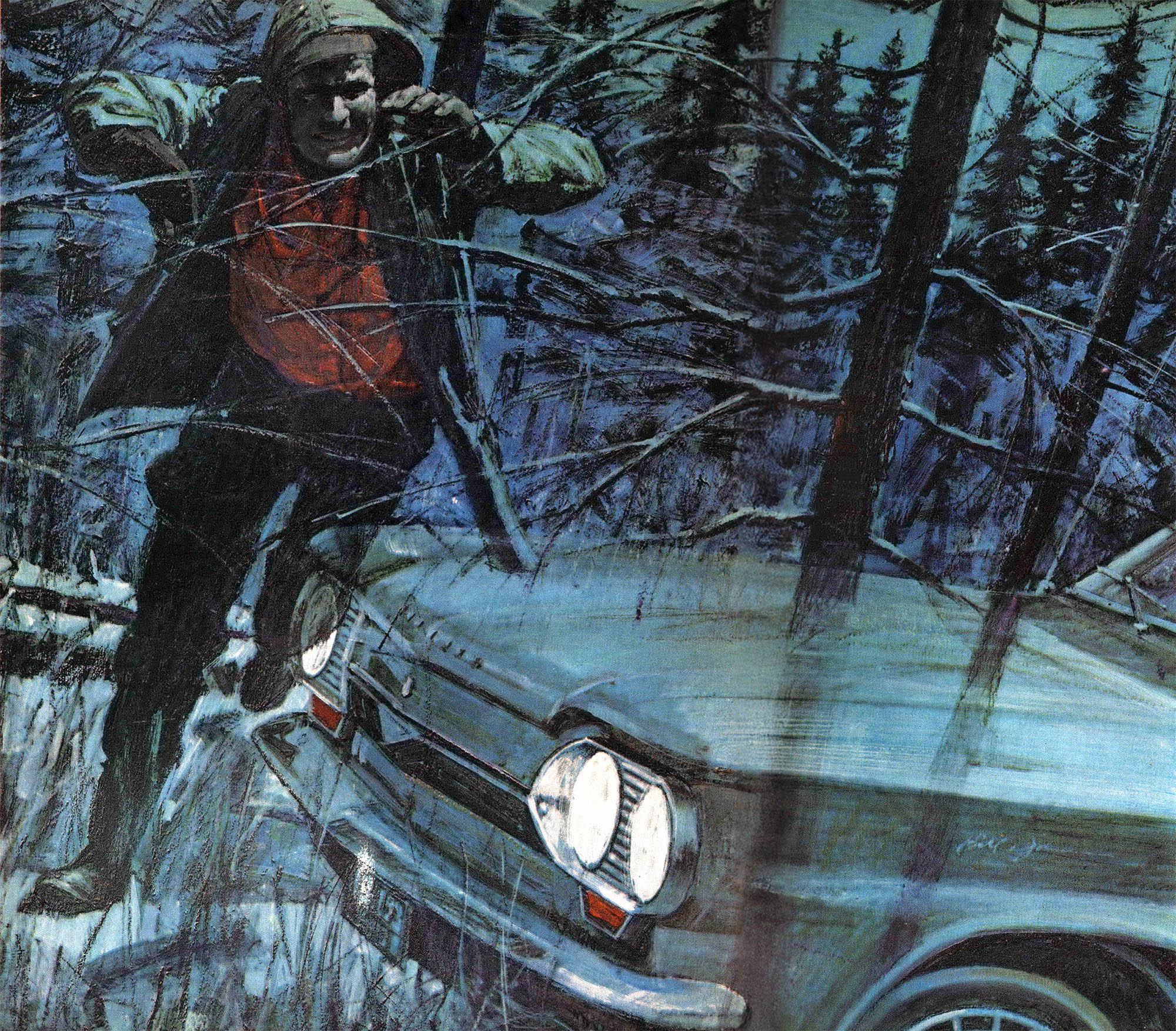

About midafternoon the animals walked over a ridge. We sneaked around to the north side of them as soon as they disappeared over the skyline. We made the stalk through low conifers, and then a funny thing happened.

We thought we were about 200 yards from the caribou when suddenly we blundered into the midst of a much larger herd. Caribou were getting up all around us — some only a few yards away. I saw racks of antlers everywhere I looked and got excited. Then I heard Don whispering to me:

“There’s the biggest bull to your right. Knock him down.”

I was using a .30/06 Springfield sporter that Don had stocked for me and 150-grain bullets that Don had hand loaded. I found the big bull’s back in my Bushnell 4X scope and touched the trigger. The caribou never moved. He just hunched his back and collapsed.

I was as excited as a kid at Christmas. Don con gratulated me and then took pictures of me posing with my trophy. We cut out part of the hindquarter of meat, and Don caped out the head. The sun was low when we took off for camp.

We knew we had to go southeast, and we took a com pass bearing on a faraway high ridge that we guessed was the same one we’d climbed near Fiddle Lake. When we reached it, we looked down on a lake that we were sure was the lake we were camped on.

In the lowlands of pine and spruce the going got tough, and darkness came on fast. Don decided it was senseless to stagger around in that jungle when we couldn’t see where we were going.

“We can’t be more than a mile from camp,” he said. “But we’d better stay here for the night.”

We built a roaring fire, sliced some meat, and cooked it on forked sticks. Even without salt, those steaks tasted great. After eating, we made beds out of pine boughs, built up the fire, and went to sleep.

I woke up shivering in the middle of the night. I built the fire back to a roaring blaze and went back to sleep. In an hour I was up again. I couldn’t relax, though Don was sleeping soundly.

At 4 a.m. a pink glow began building in the eastern sky and combined with the light of a full moon to bathe the wilderness in an eerie glow.

We were on our way when it was barely light enough to travel. What we had thought was our campsite lake turned out to be a strange lake, so we went back up the ridge we had crossed the previous evening. We figured we should be able to see Fiddle Lake from the high vantage point. By the time we reached the top of the ridge, the sky had clouded and a heavy wet mist filled the air. We couldn’t see any lake that resembled Fiddle, but we spotted another lake to the north that looked like ours, so we walked fast.

Back in the lowlands we hit swamps and bogs that made traveling extremely tough. We reached the lake about noon only to find we were wrong again. We’d been walking for eight hours and we were bushed. We were well aware by now that the high ridge

we had climbed wasn’t the ridge we had thought it was.

Now rain began coming down in sheets, and we decided to dry our clothes. We broke large branches off pine trees and shaped a lean-to near some rocks. Then we built a big fire. By the time we cooked some meat, the afternoon was well along and the rain was still pouring. We decided to stay right where we were for the night. Then Don said something that suddenly made me realize the seriousness of our situation.

“Unless you insist on saving that head for mounting,” he said, “I think we’d better skin it out. That piece of pelt will keep our heads ands shoulder dry while we try to sleep.”

At dark we heard three series of three shots each, far in the distance. We knew the shots were fired by Terry and Bob in camp, and our spirits soared. We noted the direction the shots came from, then I replied with two series of two shots. Though we were elated, I was to learn days later that our companions were fraught with discouragement at the same moment. They didn’t hear my answering gun fire.

The next morning three inches of snow was on the ground, the temperature was in the low 20’s, and Don had developed a bad cold. Though we had huddled together all night, we’d slept hardly at all, and our strength was fading fast. Before we started travel ing I fired t”,co shots but got no reply.

We walked to a high ridge directly in line with the sounds of the previous night’s gunfire. When we reached the top we saw a small lake far in the distance. We were positive we were looking at our campsite lake. We jumped up and down and hugged each other.

“That’s our lake,” Don shouted. “We’ve got it made now!”

When we got to that lake three hours later, we were exhausted. Our hopes crashed when we realized the lake was another strange body of water.

In the afternoon we found two sets of wandering footprints in the snow. We tried to follow them, but they circled and crossed in confusing trails. Eventually we doubled back on our own bootprints.

“Must be hunters,” Don said. “There must be a camp around here some where, but we better head in the direction of the signal shots we heard last night.”

We heard distant shots late in the day, but they seemed to come from three different directions. Occasionally we fired three spaced shots, but we got no replies.

DON LOOKED awfully sick. He didn’t say so, but I knew he couldn’t walk much farther.

“You stay here and rest,” I told him when we reached an open spot in the bush. “I’ll scout ahead a ways, then come back.”

I didn’t panic. I knew I had to live with my faith and not go off the deep end. But I also knew Don needed medical attention fast, so I stumbled through the jungles of thickets for four hours without stopping. Brush and briers ripped my pants to shreds. My legs were scratched and bleeding by the time I staggered to the shore of an other unfamiliar lake.

Then I saw a sight that almost made me drop to my knees and say a prayer of thanksgiving. Across the small lake I saw a tent and a beached canoe.

I yelled, but there was no sign of life near the camp. I came to a waist-deep stream and waded right across it. Time after time I came to a swamp or a spongy bog that I couldn’t cross, and I’d have to backtrack. Finally, I got most of the way around the lake and stumbled out to the shoreline. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

There was no tent. There was no canoe. The whole thing had been a hallucination.

Finally I pulled myself together and headed back toward Don. I walked the ridges to take advantage of the easier going above the tangled thickets and bogs.

When I reached the spot where I’d left Don, he was gone. I hollered but got no answer. I was terrified now.

I found Don’s tracks in the snow and took off in a last burst of energy. I’d walked so many hours that I could hardly lift my legs. My hip joints seemed to be tearing from their sockets, and my knees felt as hot as fire. But I kept going and finally heard Don yelling at me from the other side of a small lake. I turned around and saw him standing on the shore near a beached canoe.

“Bring the canoe over, Don,” I stammered. “I can’t walk any more.”

Then Don’s voice bounced around in my brain, and I finally put the words together: “There’s no canoe, Guy. Just stay where you are.”

That night we found a small cave, a depression two feet high and three feet long under a boulder. We were too exhausted to build a fire, so we just huddled together in the cave and tried to sleep.

I had terrible dreams. One time I dreamt that some men in a station wagon drove right up to our cave. Every detail of our terrain was perfect in that dream.

I heard the men talking and saw the lights of the car. I jumped up and ran to meet them. I ran smack into a tree. Stars exploded in my head, and I awoke flat on the ground, 15 feet from the cave. I was freezing cold.

There was no station wagon. There was just terror and despair.

The next morning, our fourth day, Don was critically ill.

“My lungs arc filling up,” he said. “I had pneumonia when I was a kid, and I remember the feeling.”

We didn’t get very far that day. It was bitter, and we hadn’t been dry for days. We were more dead than alive, and hardly able to walk. We figured rescue parties would be looking for us by now, and we considered staying right where we were. But the brush around us was so thick that nobody could possibly have seen us from the air. We decided to struggle on till we found a clearing near a lake.

We were out of ammunition, so we left rifles, binoculars, and Don’s carmera in the bush. All we had left were our compasses, knives, the piece of caribou skin, and my lighter. Don was a nonsmoker, so we had no matches.

We managed to struggle along about two miles that day. In late afternoon we stopped at a little glade in a thicket of spruce. I got a fire going with my lighter and managed to cut some pine boughs for beds. We simply fell in our tracks, too exhausted and weak to move.

After another nearly sleepless night of shivering and bad dreams, I knew we were done traveling. Don was so sick he couldn’t walk. He asked for water, and I had to bring him some in my mouth because we didn’t have a container. He must have known he

was slowly dying, but he never mentioned it, and he never gave up.

There was nothing I could do for Don, so I decided to look for landmarks. I staggered out on the shore of a lake only 200 yards from where we’d spent the night and found a little parklike spot on a point jutting out from shore. I helped Don to the new spot and then built a big fire. I found a lot of blueberries and managed to swallow some, but Don couldn’t eat even one.

Sometime later I heard a plane. The roar of engines became louder and louder, and I leaped up and threw green spruce branches on the fire. A maroon-and-white twin-engine plane went over us about 300 feet high, and I was positive the pilot would see the smoke from my fire.

Incredibly, he didn’t, and the plane drowned on out of sight and hearing.

The plane, of course, was searching for us, but I didn’t learn till later that the search had just begun that day. Terry and Bob had been frantic when we didn’t return the first night. They had spent the next four days looking for us and firing signal shots. In all, they fired three boxes of rifle cartridges and three boxes of shotgun shells. They had no way of getting word out that we were lost.

On the fifth day, Terry and Bob had met a hunter trying to find his way back to his camp on Fiddle Lake. The three of them eventually found the camp and took a canoe to a larger camp across the big lake. By chance, Ted Bennett was there. He’d flown in to our camp to pick us up on schedule, had found nobody, so had flown over to the Fiddle Lake camp. Terry and Bob poured out their story, Ted got on his radio, and the search was on with in hours.

I learned later that the Royal Canadian Air Force had sent search planes and a search helicopter out of Goose Bay, Labrador. Several ground parties totaling about 20 men had joined the search after being flown out of Schefferville. But that’s a huge country; nobody came close to finding us.

The fifth night an icy rain poured down so hard that I couldn’t keep the fire going, and I knew I couldn’t start I another one. My lighter wick had, stopped igniting two days before. but I’d solved the problem by taking the cotton out of the lighter and striking the flint directly to it. That trick had I enabled me to start two more fires. But the last time the cotton had barely: ignited. I knew we’d felt our last heat, and our last hope of signaling vanished.

The next three clays were horrible nightmares of snow, rain, awful cold, and hopelessness. Don couldn’t get to his feet and hadn’t eaten for clays. I managed to keep down a few blueberries. I dozed most of the time, and between dozes I made short hikes in various directions to no avail.

Near evening of the eighth day, I heard an engine that I assumed was a plane. Don drew a fatigued breath and listened intently.

“That’s no plane.” he said. “That’s an outboard out on the lake.”

The sound of the motor came closer, then faded into the distance.

The ninth day I saw two planes, one in the morning and one about noon. The second plane was close, and I frantically waved my arms. The exertion proved too much, and I blacked out. When I came to, there was no sight or sound of the plane. A wave of depression engulfed me.

Late in the afternoon we heard the motor again, and this time the drone of the engine kept getting louder and louder. In a daze, I suddenly realized that the boat was close.

My mind cleared, and then I saw a canoe with three men in it appear be tween two small islands about 150 yards away. The canoe disappeared behind the second island and then the sounds of the motor began moving away. Suddenly the motor stopped.

“Don,” I stammered, “if you’ve ever screamed in your life, do it now. your head off!’”

We screamed like two crazy men. I saw the canoe move from behind an other island. The men were paddling away from us. I’ve never been so discouraged and dumbfounded in my life.

“My God, Don,” I gasped, “they’re not coming! They must have heard us, but they’re not coming.”

The canoe moved on a few yards, then suddenly turned and began head ing broadside to us. Abruptly the men turned the canoe straight at our rock point and waved at me. My emotion at that moment was overpowering.

When the canoe beached, the three men stared at me as if I were a creature from another world. Then they locked at Don, and somebody said: “Let’s hurry it up.”

It was Friday, September 29. We’d been lost for nine days.

The men carried Don to the canoe. I managed to get in under my own power.

“We’re safe now,” I heard Don mutter. “We licked it.”

Those were the last coherent words that Don ever said.

The motor was started. and a half hour later we reached a tent camp on the far side of the lake. Some there men were there, and they carried Don into a big wall tent. Anxious hands peeled off our wet rags. then dressed us in dry long underwear and helped us into warm sleeping bags. It was too hot in the bag for me. I crawled out and drank some hot broth and asked for food.

“No solids yet,” somebody said. “If you swallow too much too fast, you’ll tear your guts out.”

Later on I had some tea and sugar and more broth. Then I fell asleep.

The next morning somebody gave me clothes. I walked a bit, smoked a couple of cigarettes, and went back to sleep. That afternoon I learned the details of our rescue.

The rescue camp was 50 miles north of where our ordeal began. It belonged to a party of eight hunters from Maine. Girard Rioux from Monmouth, Maine, his brother Bert, and Topper Nelson had been lake-trout fishing when they found us. They’d heard our yells but couldn’t come directly to us because of rocky shallows.

Since we’d been rescued, Don had swallowed nothing but a few spoonfuls of broth. and they hadn’t stayed down. But I felt sure he’d make it. Ironically, Ted Bennett had been at the Rioux camp earlier the same day we were found. He had flown out of there only half an hour before we were brought to safety. If he’d stayed a little longer he could have flown Don to the hospital in Schefferville. But Ted had no way of knowing about the rescue, and the next three days were so foggy that he couldn’t fly.

About 5:30 on the evening of September 30, I went outside the tent for a quick smoke. When I returned, Don was half out of his sleeping bag. I tried to get him back into the bag and he felt cold as ice.

I screamed for help, and several men rushed into the tent and began rubbing and massaging Don’s arms and legs. I tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation for a long time, but I knew deep-down that I was working on a lifeless body.

I remember people trying to force me outside the tent, but I wouldn’t go. I stayed in there with Don’s body for hours and cried like a baby. Eventually, Girard brought me some whisky. I drank it, but it didn’t help. I finally went outside. A big bonfire was blazing there, and some of the fellows stayed up with me all night.

On Monday, October 2, the weather cleared enough for flying. Girard had spread a yellow blanket near the water’s edge as a distress signal, and three French-Canadian hunters spotted it from their float plane. I recall the pilot’s name was Doug, and he flew me to Schefferville. I telephoned my wife from the police station, and blurted out the tragic story of Don’s death.

Terry Brandon and Bob Hammond had stayed in camp for eight days be fore returning to Schefferville to await news from the search parties. The po ice notified them of my return, and they came running in as I finished my phone call. The three of us embraced each other with a mixture of joy and sorrow.

Frostbite and a kidney infection kept me in the hospital for 2 1/2 days. I finally flew back to Detroit on October 6.

In spite of the terrible ordeal, my desire to hunt and camp remains as strong as ever. I look forward to more big-game trips. But I’ll never walk over the first hill in strange country without taking some very definite precautions.

Read Next: Lost for Ten Terrible Days

I’ll never leave camp without a survival kit and a good supply of water proof matches. I’ll also pack raingear and a plastic fold-up tarp. If a man can stay dry and warm, he can con serve a lot of strength. Even if I have maps of the area I’ll carry a few of the new pen-size emergency flares. If Don and I had had a couple of flares, I’m sure he would be alive today.

Our mistake was in walking into unknown wilderness completely unprepared for even an overnight stay. I’ll never make that mistake again.

Read the full article here