This story, “My Goat Was High,” appeared in the August 1970 issue of Outdoor Life.

RON MARTIN WAS NOT the silent type of guide. He lowered his 6X binoculars and gave me a dry grin.

“There are your goats,” he said, “right on top. Think you’re up to going after them?”

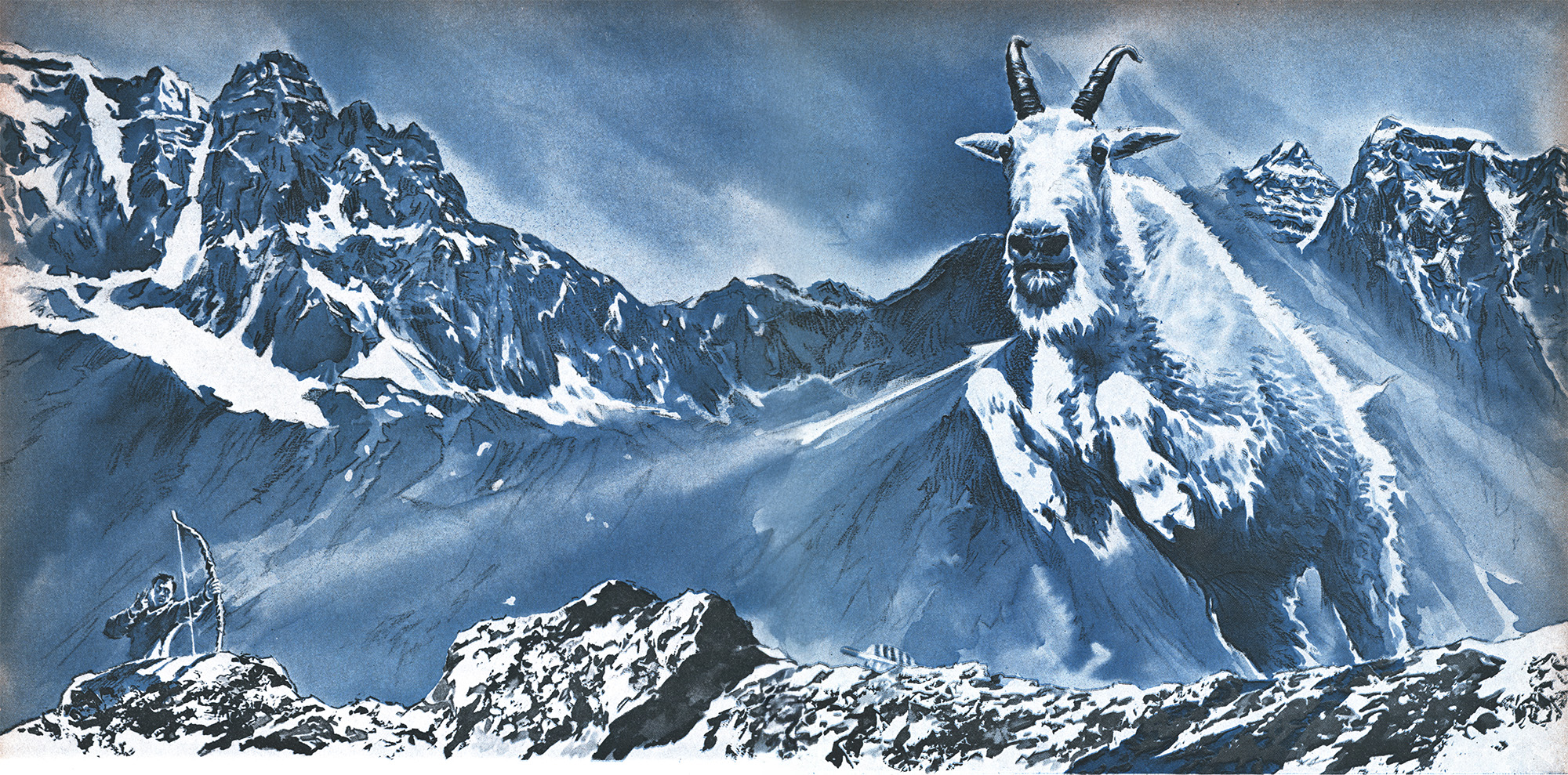

My 7X glasses were a little stronger than his. I focused them where he indicated, at the very summit of the 8,000-foot mountain across Mosquito Lake from our camp. On the skyline, strung along a ridge as thin and sharp as a knife blade, with bare rock falling away in dizzying slopes on either side, were five objects that might have been small white stones.

“Those are goats?” I thought to myself. “Are they good ones?” I asked Ron.

“Up there by themselves, they’re old billies,” he replied. “Sure to be a good head or two in the bunch.”

“Then I’m up to trying,” I told him.

This was a hunt I had dreamed about for years, and no mountain was going to keep me from trying for a trophy goat. I’d be under other handicaps, too. I planned to bag one of those skyline billies with a bow — a feat that I realized would take some doing.

At the time of this hunt I was 54 years old and lived in Brighton, Michigan, where I was a real-estate developer. I have since moved with my family to Clarkston, Washington, just across the Snake River from Idaho. I grew up in farming country around Lansing, Michigan, and started hunting rabbits and pheasants as a young boy. But I never cared much for big-game hunting until I took up bowhunting. That was in 1948, and I haven’t carried a rifle since. Prior to this goat hunt I had bow killed 11 whitetail deer in Michigan, a mule deer in Oregon, and a javelina in Arizona. The more I bow hunted, the better I liked it – and the more I itched to make an Alaskan hunt.

A few years ago in July, my Alaska trip materialized. I hitched a house trailer to our four-wheel-drive vehicle and headed for Seattle, Washing ton, with my wife Mary and our two boys, Andy, 14, and Dan, 12. We spent a few days in Seattle and then headed for the Alaska Highway on a trip that we had talked about for a long time.

At Dawson Creek, British Columbia, we rendezvoused with Tommy and Bernice Thompson, friends from Brighton. They had a tent outfit along, and we loafed up the highway, fishing for northern pike and grayling and having a great family vacation, camping-out style. At Whitehorse, Yukon, my brother Lawrence joined us, and at Haines Junction, early in August, we all turned south on the Haines Highway and headed into southeastern Alaska.

I had hoped all along to sandwich in a trophy hunt of some kind while I was in Alaska, but with such a large party I couldn’t very well hold things up while I traipsed off for a week or two on a packtrip. And from talking with people along the road I learned that a packtrip was almost the only way to make a trophy hunt.

But when we got to Haines I heard a different story. This was topflight goat country, I was told, and excellent hunting areas lay within a day’s hike of the highway. But there was a hitch.

“It’s too early to hunt goats,” half a dozen people said.

“But the season is open,” I protested.

“Sure,” one filling-station man agreed, “but the goats don’t know it. They’re still up on top. We don’t hunt ’em until the snow comes and drives ’em down. Who wants to climb all the way up a mountain for a goat?”

I decided I did.

The next problem was to find a licensed guide. Though goats were plentiful in the Haines area, few nonresidents hunted there, and guides were scarce. The game regulations prohibited nonresidents from hunting goats with out a guide.

Finally somebody sent me to Tom Katzeek, a Chilkat man living at Klukwan, a small Indian community a few miles north of Haines. Tom had a guide’s license and a good reputation, but he was busy on a truck-driving job. However, he told me that his stepson Ron Martin, 20, had just applied for his first guide’s license and would take me out as soon as it came.

Then the two of them learned that I was a bowhunter, and their enthusiasm cooled. They had never hunted with a bowman, and I could see they weren’t eager to begin. Wouldn’t I at least take a gun along? I shook my head.

“If I kill a goat it will be with a bow or not at all,” I said firmly.

Katzeek was equally blunt.

“If a rifle hunter hires us we guarantee him a shot at a goat,” he explained, “but we can’t guarantee you anything. Ron will take you up and show you a goat. The rest is up to you.”

“That’s O.K.,” I agreed.

We completed our arrangements on Saturday. Ron and I would start the hunt Monday morning. Our party drove to Mosquito Lake, 30 miles up the road from Haines, and camped.

Despite the name, there were few mosquitoes, and we put in a good weekend fishing for trout and salmon. Across the lake from camp soared a huge mountain, timbered about halfway up and topping out with bare slopes and a knife-edge ridge. The Chilkat called it Goat Mountain and said that it rose 8,000 feet above the lake. We kept glassing the upper slopes and wondering whether the mountain deserved its name; we couldn’t see anything that looked like goats.

Then on Monday morning Ron showed up and pointed out the five billies on the ridge at the very summit. Unfortunately, Ron’s license had not yet come through; nor did it come on Tuesday. When Wednesday morning came and I still had no guide, I gave up. I couldn’t delay the party any longer. At 10 a.m. we were packed and ready to leave. Then Ron drove in.

“I’ve got my license,” he reported proudly. “I’ll bring the airboat up the river and we can start at noon.”

I let the others decide whether we should stay. Ron had said that with a gun the hunt would take two days but with me it might take four. Everyone voted in my favor, however, so I told Ron to get things rolling while we unpacked.

An hour after noon Ron and I beached his airboat at the foot of Goat Mountain and started the climb. We were travel ing as light as possible. I had my bow, which has a 57-pound pull, and a dozen arrows. This was brown-bear country, both along the beach and up in the mountains, so Ron was carrying a Winchester .30/06 as insurance. We had down sleeping bags, and I had slipped in a light air mattress. Our only shelter was a square of plastic big enough to cover the two bags. We had the usual cooking gear and just enough canned beans, sandwiches, and coffee to last two days. If we were gone longer we’d be on short rations.

There would be no water on the way up, from the time we left the lake until we reached the peak. There we’d find snow. I carried a one-quart canteen. An hour after we started to climb, Ron confessed that he had forgotten to bring water. The quart would have to hold us for 24 hours, until we got to the summit.

Ron had his glasses, but I had left mine at camp to save weight. I was using a packsack, he a packboard. (From now on it’ll be a board for me too. That trip converted me.)

For a while we had fairly easy going through open timber. Ron was turning out to be a fine guide — educated, a good talker, fun to be with.

The slope grew steeper, and we came to a belt of alder and devil’s club so thick that Ron had to hack through it with a machete. Mary later picked devil’s-club thorns out of my festered hands for a week.

We cut and sweated and panted our way up through dense thickets for four or five hours. At dark we halted, tired and hungry, just under the upper slopes. We’d make a siwash camp here for the night.

We could find no dry wood, but during the afternoon Ron had gathered pitch bark and stuffed it into his pack. With it he got a tiny fire going. We heated a can of beans, made coffee, and rounded out our supper with cold sandwiches. The fire died, but we spread the plastic sheet over our bags and slept warm and comfortable.

That night the weather, which had been fine for a week, took a bad turn. We were awakened by icy rain, and at daybreak our gear was covered with wet snow and the top of the mountain lay hidden in clouds. Climbing would be dangerous.

“We don’t hunt in a storm like this,” Ron told me. “Too risky.”

I understood that by “we” Ron meant the Chilkat; he made no suggestion that he and I should turn back.

Everything was soaking wet that morning, and we made no attempt to build a breakfast fire. We ate cold sandwiches and sipped water. An hour after daylight we were ready to start for the top. We left our bags and all our gear, except my bow and Ron’s rifle, at the camp. We’d pick everything up on the way down.

Fog and clouds blanketed the slope above us, and one snow squall after an other swept down from the summit. We had climbed about an hour when the clouds started to break, a patch of blue sky appeared, and the sun peeped out briefly. We stopped and glassed the mountain as the fog lifted, and Ron soon spotted a scattered band of 10 or 12 goats grazing in a grassy basin above and to our right. They were all nannies and kids, but at least they proved that we were up in goat country.

Then the clouds rolled away higher up, and finally we could see the skyline ridge on the summit. The guide swept the ridge with his glasses and let out a sharp grunt of satisfaction.

“They’re waiting for us,” he said, handing me the binoculars.

There, bedded in shallow depressions along the ridge, almost exactly where we had seen them from camp three days before, were three big goats, as serene and contented as cows in a pasture. Even with Ron’s 6X glasses I could see that all the goats were big billies. Any one of the heads looked good enough to satisfy me. I was wet and winded from the climb, but that sight revived me.

Five minutes later the clouds socked in again, the air was full of snow, and we were hidden from the goats as if a curtain had been drawn between us.

Five minutes later the clouds socked in again, the air was full of snow, and we were hidden from the goats as if a curtain had been drawn between us. We started up once more.

“We’ll have to watch out for that bunch under the top,” Ron warned. “If we blunder into them they’ll be almost sure to spook the three on the ridge.” We had climbed pretty high by then, but the altitude didn’t seem to bother me much, probably because we were moving slowly and carefully and taking frequent stops.

After we had climbed another hour, up slopes of bare rock that grew steeper and steeper, the clouds broke away again. We were above the band of nannies and kids, but as more and more of the high slopes were uncovered we began to see other goats, scattered here and there on both sides of us, some above, some below. Before the fog and snow closed in again we had counted 40.

It was about 1 p.m. when we finally hit the top. My canteen had been bone dry for two hours, and the first thing we did was look for water. On the far slope of the summit a big snowfield fell away to a glacier. We scooped out a small hollow at the edge of a melting bank, and when enough water had trickled into it we drank our fill and replenished the canteen.

About that time the sun came out again and we got another look at our three goats. They were still lying on the skyline, a quarter-mile away, and they had a view like nothing I had ever expected to see. They could look for 20 or 25 miles in every direction, mostly over a jumble of peaks, snowfields, and glaciers. More important to them, they could look down the mountain 3,000 feet or more on either side and spot any danger moving up toward them.

I had read that goats are seldom bothered by natural enemies, and I was beginning to see why. With those billies doing sentry duty on the summit, none of the bands below were in much danger. I was also learning firsthand why a good goat head ranks among the top trophies on this continent. They may be easy to hunt when snow drives them down off the peaks, as I had been told, but it’s another story when they are on their late-summer range.

The stalk, if you could call it that, was the strangest thing I have ever done on a hunt. The knife-edged ridge we had seen earlier formed the summit of the mountain; it climbed and dipped along the crest like a thin slab of rock tipped up on edge, with smooth slopes steeper than a house roof pitching down on either side, bare for 1,000 feet, then covered with moss and sparse grass. A goat path, worn smooth by generations of travel but hardly six inches wide, wound along the upturned edge of the slab. Our three goats were lying in that narrow trail, and we’d have to follow it to get to them.

The goats were in the open, and so were we. There were no rocks for cover, and we made no attempt to sneak or crawl. We stood upright and walked slowly, giving most of our attention to our footing, moving only when clouds hid us, remaining motionless whenever they opened up. In clear weather a stalk would have been hopeless.

Fortunately, the goats were not suspicious. Two or three times, in the brief minutes when the visibility cleared, I could have sworn that the nearest billy was looking us straight in the eyes. But he did nothing about it. The goats had not been hunted hard, if at all, and I’m sure they had never seen a man at the top of the mountain before. Ron himself had never been up there and knew no one who had.

We stood upright and walked slowly, giving most of our attention to our footing, moving only when clouds hid us, remaining motionless whenever they opened up.

Most of the time snow and clouds prevented us from looking down, but when ever they cleared we got a terrifying view of the precipitous drop on either side. During one of those intervals Ron gave me a devilish grin and whispered. “They call me The Goat, down in Kluckwan.”

In a few places the trail was blocked by big slabs of granite, around which the animals had detoured. We had no choice but to do the same. It was risky, but by setting our feet carefully in the depressions made by many generations of goats, we kept our footing and inched across the steep slope. We sent a lot of loose rock rolling down, and I asked my guide whether the noise might spook the goats.

“They’re used to that,” he explained. “They roll rocks too. As long as they can’t see us they won’t be spooked.”

We’d had a good look now at all three billies, and their horns all looked about equal. We agreed I’d try for the nearest. He was lying in a shallow bed where the path widened briefly, his head and back outlined against the sky. I’d shoot as soon as we got within range.

We came to a rock three times as big as an average house. One end jutted across the trail, and we had to drop off the ridge once more to get around it. When we climbed back to the goat path. our billy was only 100 yards ahead, hidden in a thick cloud. We covered about 25 of those yards, walking as carefully as if we were trampling eggs. Then the fog opened up and we were looking at the goat and he was looking at us.

“Shoot!” Ron grunted.

“Too far,” I whispered back.

Ron was in the lead, and the path was too narrow for me to step by or shoot around him. Before the goat could decide what he was seeing, a tongue of cloud drifted between us. Ron and I hung onto each other for balance as I squeezed around him. Then we cat footed ahead again. When I got my next glimpse of the goat he was 50 yards away, looking hard in our direction. I didn’t dare wait any longer.

I slammed an arrow and saw it clatter on the rocks just in front of the goat. But the billy didn’t spook. He got to his feet, stretched, and turned deliberately to walk away. I was using a bow quiver that held three arrows, and I had another on the way before he took the first step.

That shot was better, but not much.

I saw the arrow graze the billy’s shoulder and cut away a patch of white hair, but I didn’t think it had penetrated. He spun around and went down the steep slope at a lumbering gallop, and I tried to swallow the fact that my goat hunt was finished and that I had blown it. I looked around at Ron. He didn’t say a word, but he had “I told you so” written all over his face.

Our goat had spooked every other goat within hearing. Up ahead the two other billies walked off the ridge. Then two more, which had been lying farther along the path, out of our sight, went calmly down after them. That account ed for all five of the big ones, but in the next 10 minutes we saw at least a dozen more goats on the move below us, all working down the slope to get out of the danger zone.

We followed the trail to the spot where my goat had been hit. There we found a few drops of blood on rocks – just enough to show that I had cut the skin – and saw my arrow lying in the path a few yards away, with a little blood on the head. Apparently I had inflicted only a shallow flesh wound, for there was no blood sign where the billy had left the path.

“Well, since he got away I’m glad he’s not carrying an arrow,” I told the guide. Ron didn’t have much to say, but it was easy to see what he was thinking. All that was left now was the long, hard climb off the mountain.

Suddenly Ron grabbed my arm and pointed down.

“There they come back,” he blurted. A quarter-mile below us our five billies were walking steadily in single file back up to their skyline trail. For a second I couldn’t believe my eyes, but then I realized that this development was not so strange after all, for none of the goats had made us out, my bow had made no noise, and the billy I had creased didn’t know what had hurt him.

In time of danger the natural direction for a goat to take is up. He knows that his best hope of shaking off his enemies is to head for the top. As trophy game animals go, the goat is on the phlegmatic side — not nearly as excitable and spooky as a deer or a sheep. This band of billies had run off the ridge in momentary alarm, but half a mile down they had stopped, collected their wits, and turned around. None of the five showed any sign of being hit.

One whiff of blood was all he needed. He made the only fast move I had seen a goat make on the entire hunt — and it was really fast. He swapped ends and jumped like a deer, and in that same instant my arrow sailed off the string.

We got behind a rock to wait for them. They angled up until they reached the goat path, then turned onto it and came straight for us, still walking in single file, heads down, acting as if they didn’t have a worry in the world. But we had been guilty of one small over sight. In our excitement at seeing them coming back, we had neglected to pick up my blood-stained arrow.

I’ve never had buck fever, and I guess I’m not susceptible to it. If I were, that situation certainly would have given me a full-blown case. I was half hidden behind the rock, and Ron was crouched beside me. The only place I could find to stand was on a tilted slab that teetered and threatened to slide out from under me. The goats came on, closer and closer, until the one in the lead was only 50 yards away. I could feel my heart thumping against my ribs.

I wanted a sure thing this time. With my eyes I marked a boulder about 20 yards off. When the first goat reached it, I’d take him. I had the bow up and the arrow halfway back when, 10 steps short of the boulder, the lead billy came to my arrow lying in the path. One whiff of blood was all he needed. He made the only fast move I had seen a goat make on the entire hunt — and it was really fast. He swapped ends and jumped like a deer, and in that same instant my arrow sailed off the string. The arrow caught the billy quartering behind the ribs, and I saw it sink in up to the feathers. His left hindquarters failed, he half fell. Then he pulled himself together and bounded up over the crest and out of sight. The four other goats went with him, and for once they too were in a hurry.

I like to wait 20 to 30 minutes before following a wounded animal, but now another hard snow squall swept across the ridge and we knew that both the blood trail and the goat would be covered in a matter of minutes, so we hurried after him. We scrambled across the summit and turned down, and before we had taken a dozen steps Ron yelled, “There he is!”

My arrow had ranged forward into the goat’s lungs, and he had traveled only 125 yards, bringing up stone-dead against a big boulder. Ron was all smiles now, and I was as tickled as if it had been my first big-game trophy. If the rocks hadn’t been so slippery I guess we’d have danced a jig.

I had killed a big, heavy billy (Ron estimated his weight at close to 300 pounds) with a good head. Eleven months later the head was measured by William R. Vanderhoef of Boise, Idaho, an official measurer for the Pope and Young Club, which keeps records of bowhunting trophies. It scored 47, putting it in second place at that time on the Pope and Young list.

I wanted pictures, but it was snowing too hard to take them there and Ron decided that the bare slope of the mountain was too slippery for us to pack the meat down.

“We’ll take the head and let the rest roll,” he said.

After the head was off we dragged the carcass clear of the boulder and gave it a nudge. It rolled and bounced and slid, gaining speed as it fell, until it was lost to sight in the snowstorm.

An hour later we found the carcass half a mile down, in a little hollow just above the brush. We dressed it out and put most of the meat into our packs. The head and meat made a heavy load, and the rest of the trip down the mountain was far harder than the climb up had been.

We got back to our camp at dark. We were wet, cold, hungry, and worn to a frazzle. There wasn’t a stick of dry wood to be found, but again we got a little fire going with the pitch bark Ron had cached. We made coffee and heated a can of beans, saving our remaining two sandwiches for breakfast.

That night was long and miserable. The wind blew hard, snow pelted down, and we couldn’t find enough dead stuff to keep the fire going. I huddled in my light bag and shivered through most of the night.

Read More: The Best Recurve and Longbows of 2025, Tested

We didn’t bother with a fire the next morning. We ate our sandwiches and pulled out right after daylight, slogging down through the alder and devil’s-club. My load of goat meat seemed to get heavier and heavier, and before we reached the bottom I thought my knees were going to buckle at every step. But we finally made it to the lake, shucked our packs, cranked up the airboat, and roared away for camp. We got there at noon, and Mary made us a huge hot meal. Food had never tasted better.

We had been gone 48 hours, climbed 8,000 feet up and 8,000 down, siwashed two nights in rain and snow, seen more than 100 goats, and gathered in a fine billy. The hunt had cost me $75, apart from my nonresident license fee. As my boy Andy remarked afterward, that was certainly a low price for such a high goat.

Read the full article here