Bobby Zylstra’s morning started a little slow, with cool weather and low clouds hanging over Missouri’s Current River on Friday. After wading a ways downstream, he started seeing a few rises here and there, and soon enough he hooked his first brown trout on a cicada pattern — a big, foam fly with a black-and-orange belly, rubber legs, and beady red eyes. As the day warmed, Zylstra heard cicadas start to sing in the treetops. He also noticed more fish rising to the bugs.

“I just saw, chomp, chomp, more consistently. And then I started seeing [trout] cruising around in really odd water, like a foot-and-a-half deep. They were looking up and actively hunting for cicadas,” Zylstra tells Outdoor Life. “This one fish was probably 10 feet in front of me, so I flipped my cicada over there and he swam over, probably about four feet, and just chomped it.”

That one fish was a 21-inch brown, the biggest Zylstra had ever caught. But he’d beat his own record twice that afternoon — first with a 23-inch brown, and then with a 26-incher — as he brought countless fish to hand, all on the same cicada pattern. At one point, he forgot to reel in as he bent over to pick up some trash in the river, and a trout hammered his fly as it hung downstream in the current.

“I heard this explosion behind me, set the hook and caught a 17-inch fish,” he says. “But it was just that kind of day.”

For anglers looking in the right places, there could be more of these days on the horizon. The cicadas are out, and even if you haven’t heard these insects in your neck of the woods, you might have heard that 2024 is a special year for the big, noisy bugs. This spring and summer will mark the largest emergence of periodical cicadas in more than 220 years as two different broods emerge simultaneously in certain corners of the country. For anglers in these areas, this means a massive influx of large, edible insects that, under the right conditions, could lead to some of the hottest surface fishing in recent memory.

All told, entomologists (bug experts) expect trillions of the bugs to emerge between now and the end of June. This is already underway in parts of the midwestern and southeastern U.S. — the core range of periodical cicadas. Some anglers there have already seen the flip switch, while others are anxiously awaiting the bugs to show up in sufficient numbers.

Just like most types of fishing, the key to capitalizing on the cicada emergence is being at the right place at the right time. There are several factors at play when chasing a hatch, however, and even if you do find yourself amid a cloud of cicadas, this doesn’t always translate to lights-out fishing. Or, it could be biblical. Just ask Zylstra.

In This Article

Read straight-through this article, or click on any of the topics below to jump straight to them.

What Is the Double Cicada Emergence?

“I don’t think I’ll ever experience anything like it again. It was just such a phenomenon, like seeing the Northern Lights,” says Zylstra, who lives in Jefferson City, Missouri, and grew up in Chicago. He still vividly remembers his first experience with periodical cicadas when he was four years old on a trip to the zoo with his family: the incessant buzzing and crunching sounds of bugs underfoot as they rained from the sky and fell from the trees.

“It’s just an incredible memory that’s stuck in my brain. And then I recently got into fly fishing about four years ago, so it all started to click,” Zylstra tells Outdoor Life. He bought David Zeilinski’s recently published book, Cicada Madness, which has quickly become the go-to resource for cicada-curious anglers. “I started tracking and learning about it, and listening to [Zeilinski’s] podcasts, and then Friday just ended up being the perfect storm. On Wednesday, I’d heard from a guy on Instagram who I’ve talked to before, and he was like, ‘It’s going off on the Current.’”

For many people, especially those living in the Midwest and South, the loud buzzing of cicadas is synonymous with peak summer, which is when annual cicadas (also known as dog-day cicadas) emerge from the ground to take flight, mate, and die. These gray-and-green insects emerge on two- to five-year cycles, but the generations overlap so that they show up in decent numbers every year.

There is another type of cicada that emerges from the ground less frequently but in numbers that far overwhelm their annual cousins. Known as periodical cicadas, these insects show up every 13 or 17 years, depending on the species. Their bodies are black-and-orange, as opposed to gray-and-green, and they’re a bit larger than annual cicadas. They also have bright red eyes, whereas annual cicadas have black or brown eyes. And when they do finally emerge, they do so en masse, crawling out of the ground by the thousands.

“What’s highly unusual, especially for something as small and typically short-lived as an insect, is that they live underground for 99.5 percent of their lives, only to emerge for several weeks as adults,” says Dr. Barrett Klein, an entomologist and biology professor at the University of Wisconsin La Crosse. “Another interesting aspect [of these emergences] is that you can time them with such precision that you can go out and experience not just millions, but billions or trillions of these cicadas arising from the earth.”

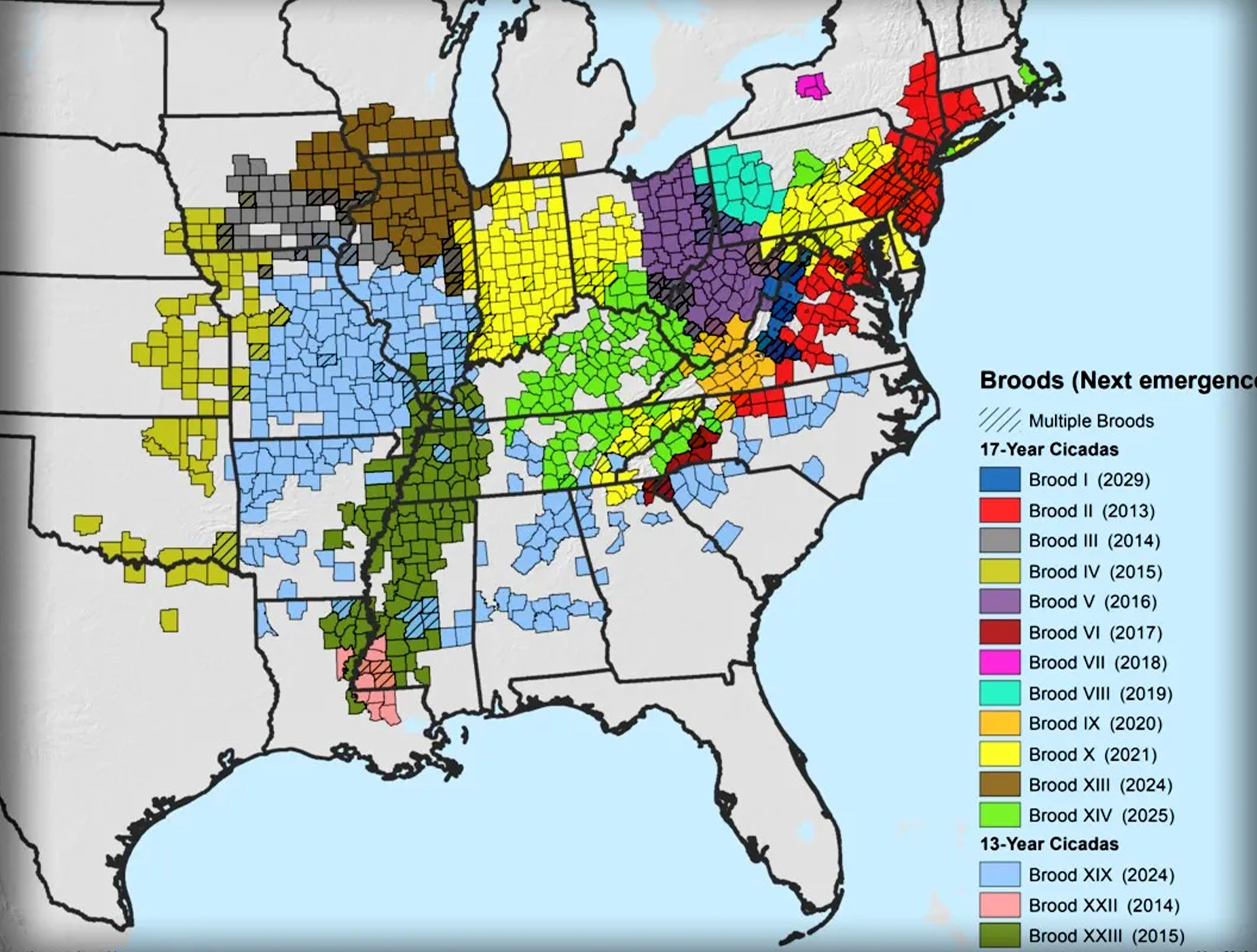

As scientists have tracked these events over time, they’ve categorized the seven species of periodical cicadas that are native to the eastern U.S. into 15 numbered broods. Brood X, for example, emerges every 17 years in parts of Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee, with the last emergence taking place in 2021. This is different from Brood XXII, which emerges every 13 years in Mississippi and Louisiana, and which emerged last in 2014.

Once in a great while, the timing lines up so that multiple broods emerge at the same time, and 2024 is one such year. For the first time since 1803, Brood XIII (known as the Northern Illinois Brood) and Brood XIX (known as the Great Southern Brood) are emerging simultaneously.

This has people like Klein understandably excited. Last week, he traveled with a group of students to witness the phenomenon in central Illinois. He calls this area an “entomo-Mecca” because it’s really the only place in the country where the two broods are emerging at the same time in the same general area.

“It really centers around Springfield, Illinois, so we made a big circle on Tuesday, and we’re confident that we hopped into the right area because we saw all three species,” Klein says. “I think our visit was a little early, because the sound wasn’t deafening. I mean, we had cicadas all over the tents and all over the trees, but it takes them about five days after they emerge to really get their voices. So, we heard distant calling but it wasn’t a cacophony.”

Naturally, the sound of millions of bugs singing in the forest is also a symphony of dinner bells for fish and wildlife. Small mammals and game birds like grouse and wild turkeys will feast on the bugs, as will black bears and other foragers. Even humans can get in on the action, and Klein points to a rich history of indigenous peoples eating cicadas, along with a host of modern-day recipes for preparing them.

And from a fish’s perspective, a once-in-a-lifetime hatch of big clumsy bugs might be too good to pass up. At least that’s what many of us are hoping for.

How to Fish the Cicada Emergence 2024

In an ideal scenario, you’ll be on the water when there are enough bugs around for the fish to key in on. All kinds of fish species will target cicadas, but for many anglers, trout and smallmouth bass are the two main quarries. Trout are especially predisposed to eating them because aquatic insects make up the majority of their diet in most places.

One of the best ways to fish the cicada emergence is with a fly rod, says Augustus Knickmeyer, a Missouri-based guide who fishes primarily on rivers in the southeastern corner of the state. Cicadas are bugs, after all, and fly fishing at its core is a means of imitating natural insects. This isn’t to say conventional tactics won’t work, however, and Knickmeyer says these anglers can still catch plenty of fish on topwaters when the fish are cooperating.

It’s possible to bait a live cicada on a hook because of how large they are, but floating imitations will typically fare better than sunken bugs. And when the feed is really on, the fish might ignore everything else in the water. Zylstra says that when he talked with other anglers on the Current last week, none of them were catching much — but they also weren’t using cicada patterns.

There are plenty of cicada flies to choose from. Most of these patterns fall into two categories: the hyper-realistic bugs that look almost identical to the real thing, and what Knickmeyer calls “impressionistic” bugs, which look a little bit like a lot of things.

Some of Knickmeyer’s favorite cicada flies are variations of the same basic foam bugs that imitate beetles, grasshoppers, and other insects. One of his go-to patterns is essentially just a larger Chubby Chernobyl tied with black and orange foam and rubber legs. As for Zylstra, he’s been fishing some large foam bugs that he bought on Etsy. He even painted up the orange underbodies with a black Sharpie to give them more contrast on the water.

Read Next: The 12 Best Bass Flies for Catching Largemouth and Smallmouth

A few basic bass poppers in the right sizes are other good patterns to carry, especially when targeting bronzebacks. These flies can move water and make a lot of noise, which helps call fish to the surface.

Conventional anglers have plenty of lure options, too. Just like with flies, there are some highly detailed topwater lures like the Grand Siglett, but most of these will cost you a pretty penny. Simpler alternatives include smaller plugs like Jitterbugs and small Torpedoes.

It’s important to work these patterns slowly and not aggressively. Cicadas are big, clumsy land-based bugs, so they can’t swim or move through the water very well, and oftentimes they’ll just twitch or flap their wings occasionally as they drown on the surface. And while it might seem counterintuitive to some dry-fly purists, you’ll want to cast with a little more force so the fly or lure lands with a splat on the surface.

“On the smallmouth side of things, it seems like most people’s tendency is to skate their flies or chug a popper really loudly,” Knickmeyer says. “But that just seems to spook the fish. Generally, I’ll have [a client] make a cast, letting it slap down, and then let it rest for a while until the rings dissipate from around the fly. Then, if anything, just kind of wiggle it.”

Zylstra says most of the trout he caught last week came on a classic dead drift, which means letting the fly move naturally with the current and not imparting any action. He was wade-fishing solo, and because the trout were feeding so aggressively on cicadas, at times he was able to get within a rod’s length of a rising fish.

“You’d see an explosion, and then give him a minute to digest the cicada he just ate. You know, let him reset. And then just flick it over there. You still had to get a good, clean drift, but if you did, he’d just engulf it.”

Fishing the Cicada Hatch Isn’t Always as Easy as It Sounds

Periodical cicadas can also present some challenges for anglers, especially when compared to aquatic insects like mayflies, terrestrial bugs like grasshoppers, and other common forage such as frogs and crayfish.

For starters, most of these food sources appear frequently and predictably enough that fish will gobble them up on sight. But periodical cicadas only show up every 13 or 17 years. And since many game fish species don’t live that long (the average lifespan for a smallie is around 15 years, compared to 10 or so years for a rainbow trout), they’ll typically only witness one big emergence in their lifetimes. This means it can take them a little longer to recognize periodical cicadas as food.

While fish in some areas might recognize annual cicadas, the general assumption among fishermen is that there typically aren’t enough of these bugs to really trigger a feeding frenzy most years.

“It’s just not the same numbers,” Knickmeyer says. “I wouldn’t say that a fish won’t take a cicada fly during those times, but it’s not gonna be something they’re really keying in on.”

Periodical cicadas, on the other hand, emerge in such huge numbers that when fish finally realize they’re a food source, they go bonkers over them. This presents another challenge, though, because fish will sometimes gorge so heavily on cicadas that they’ll get their fill overnight, or before you show up with a rod in hand. Similarly, if there are tons of cicadas falling on the water, the fish can get so overwhelmed by natural bugs that they have a hard time finding the artificial ones.

When to Fish the Cicada Emergence

If you’re wondering when the best time is to try to hit the cicada emergence, the answer is now. Or tomorrow. Or maybe yesterday. It all depends on where you’re trying to fish and what the temperatures have been like, as this is the main trigger for a periodical cicada emergence. According to the experts at the University of Illinois, the specific temperature window is when the soil reaches 64 degrees at around eight inches deep.

This typically occurs in May or June in most of the country, but it’s only the beginning. The bugs are still in their nymphal stage at this point, and they have to molt into winged adults before they can start buzzing and flying around. It then takes some time for the bugs to start singing and mating and falling into the water, which is when fish will start to notice them.

“So far what I’ve seen is that the carp and the smallmouth aren’t really keyed in on cicadas, at least not yet,” says Knickmeyer, who’s had some clients book trips specifically to fish the cicada hatch. “But the guys I’ve talked to who are fishing more on the southern rim of the Ozarks, they’re just starting to see the trout look up. And I’m hoping that maybe as [the bugs] are around longer, it’ll continue to improve.”

As for the duration of the overall emergence, Klein says that periodical cicada adults only live for a couple weeks, during which time they’re totally focused on finding a mate. After this is accomplished, they’ll start dying off in droves and the forests will quiet down, but there should still be a short window after the die-off that anglers can take advantage of. By this point, the fish that aren’t already gorged on the bugs will still be looking for stragglers.

Knickmeyer says that so far this spring, he’s seen the best surface activity during the late afternoons and early evenings. This could have something to do with the bugs getting more active as the weather warms throughout the day. Cicadas will be around rain or shine, however, and just as Zylstra saw on May 17, some of the best conditions for topwater fishing are during overcast days. Clouds provide cover, allowing big fish to move around more easily, and they block out the sun, which helps fish see bugs on the surface better.

Where to Fish the Cicada Emergence

Thanks to centuries of scientific study, we have a pretty good idea of where the two broods are emerging. A map from the U.S. Forest Service shows the Brood XIII emergence centering around northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin, along with portions of Iowa, Indiana, and Michigan. The same map shows the Brood XIX emergence occurring sporadically in southeastern states like Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas, with more dense numbers of bugs emerging in Missouri, Arkansas, and southern Illinois.

Because temperature plays such an important role in triggering the emergence, cicadas will typically pop up in the South before they do in the North. Klein says this has pretty much gone according to schedule so far this year.

“It really depends on where you are,” he explains. “Brood XIX is starting to fade in the Southeast, but Brood XIII is still on the rise, and I think the best times in Illinois and that region will actually be in a week or even two weeks. In early June, they might still be roaring in southern Wisconsin, but that’ll be the last batch.”

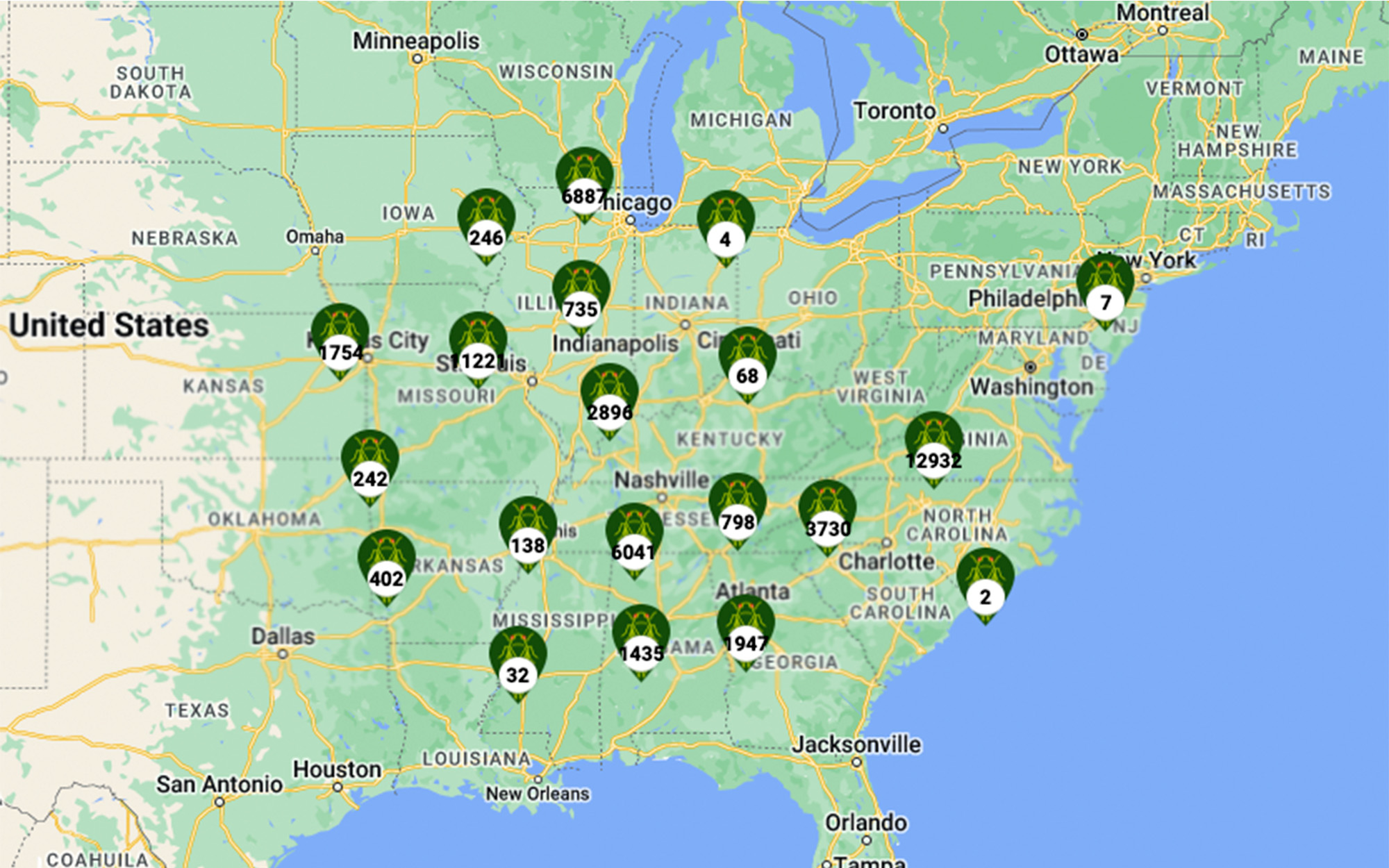

Modern technology has allowed us to pinpoint these hatches with even greater accuracy, as crowdsourcing sites like iNaturalist and Cicada Safari show the locations where people have seen and photographed periodical cicadas. This creates a living map that anglers can use to further home in on a fishing spot.

“About two and a half weeks ago is when I started hearing them in places,” Knickmeyer says of his area in southeast Missouri. “A lot of my buddies who live up in St. Louis, I think they were starting to see them a little earlier. But here in the Ozarks, it took a week after I first heard them to really hear and see cicadas consistently along the rivers.”

Read Next: How to Be a Fish Bum: These 6 Fishermen Are Living the Dream

Once you narrow down a particular region, you’ll want to seek out a specific waterbody where periodical cicadas are most likely to fall. And because the life cycles of these bugs are intimately linked to trees, your best bets are near mature, healthy forests with large tree canopies. This doesn’t mean you have to fish in the wilderness, however, and urban waterbodies with plenty of nearby trees shouldn’t be overlooked.

“I would say it’s been pretty consistent as long as you’re on a piece of water with some overhanging trees” Knickmeyer says. “I think part of it has to do with the prevalence of big, deciduous hardwoods, but that’s just my assumption [based on what I’ve seen so far]. I’m not a cicada expert.”

Another key piece of advice for scouting anglers is to use their ears. The mating songs of male cicadas (females can’t sing) are incredibly loud, and males will typically sing in large groups to attract more females. Their calls can reach volumes over 90 decibels, or as loud as a tractor or motorcycle, according to the National Institute of Health.

So, if you’re keen on big surface eats and live anywhere near the emergence zones, it’s worth your time to check out a map, hit the road, and head for the nearest buzzing sound. After all, an event like this won’t come around again until 2245.

Read the full article here