This story, “Texas Fist Fight,” appeared in the June 1955 issue of Outdoor Life.

I couldn’t have felt sorrier for myself as I sat on the long veranda of Tarpon Inn at Port Aransas, Texas, brooding over my bad luck. This was the big fishing trip of the season for me, the one I’d planned and saved for all summer, and it was a bust. For two days, the last two of my visit to this famous fishing spot, I’d been skunked. It wasn’t the weather or the water or the scarcity of fish. Conditions were O.K.; but I simply couldn’t connect. Somehow I always missed being in the right place at the right time.

“Why don’t you go down the point and cast a spoon for a while?” asked Bill Ellis, the inn’s manager, as he settled into a chair beside me. “Sometimes the pike start striking there this time of day.”

Ordinarily I welcome angling suggestions from Bill because he’s been around Mustang Island a long time and knows his stuff about local fishing. But that afternoon I was feeling too low to care — until it dawned on me he was talking about pike.

I felt a flicker of returning eagerness. Pike? No other fish he might have mentioned would have got a rise out of me, but I’d have given my right arm for a crack at a pike and I told Bill so.

I’d never seen one, but ever since I was a kid I’d read stories and looked at pictures of Florida’s fabulous snook, or robalo, and I knew that every year a few schools make their way up the Texas coast from Mexico. In Texas we call them pike, and everyone who does any Gulf fishing regards them as rare prizes-both on the end of a line and on the table.

Bill knew he’d struck a responsive chord, for a good pike run is an event in Port Aransas. I was there at the time when these runs reach their peak — in September and October — but when I prodded him for details he admitted there was no evidence such a run was in progress. He urged me to try until sunset, which wasn’t far off, and offered to drive me to the point. Reluctantly I got up and reached for my lightweight 5½-foot casting rod.

A few minutes later we were at Kline’s Point on the landward side of the island, a little sandy beach on the fringe of a wasteland of sand dunes, salt grass, and tidewater debris. Bill helped me pick out a few spoons and surface plugs we thought might turn the trick if there were snook about, then wished me luck and took off.

I threaded the end of my 12-pound-test nylon line through the rod guides, tied on a wire leader, and rigged up with a plain No. 7 spoon. Then I waded across a narrow stretch of water to the rock jetty which protects the foundations of the channel marker at the edge of the powerful tide.

The channel is Aransas Pass, the cut that runs between Mustang and St. Joseph Islands. It’s the only opening through the Texas barrier islands for miles, and serves as a deep waterway for ocean-going vessels headed to and from Corpus Christi seven miles away on the Texas mainland. It’s also a funnel through which three great bays empty their tidewaters into the Gulf of Mexico.

The terrific force of the outgoing tide was a little frightening as I balanced precariously among the rock pile’s upended boulders. A step too far into that current and I’d likely never be seen again. While I’ve fished safer places, I’ve found few that interest me more.

It was nearly sunset, and the rays of the low sun slanted against the towering sides of foreign ships as they plowed majestically out to sea. I began casting and retrieving, almost mechanically, and watched the sturdy pilot boat running up and down the channel guiding the floating giants. The gulls and pelicans, on their last fishing excursions of the day, cruised on a steady breeze and the stragglers of the shrimping fleet and a few small cruisers were wallowing in the channel chop, their masthead running lights making circles against the darkening sky.

But there were no fish. Gradually I relaxed, stopped casting, and finally called it a day when the sun was just balanced on the rim of the world. Wading back to the beach, I slowly looked over the scene before me. The point is actually the rounded corner of Mustang Island and the beacon tower, standing grotesquely on tripod legs a few yards off the point, is connected to the beach by the jetty. Behind the jetty lies a little sheltered backwater.

An elderly fisherman, pant legs rolled to his bony knees, was fishing this peaceful but unpromising spot, and I waded over to pass the time of day. As I neared him I saw that his rod was heavy and his tackle ill-matched. He was fishing bottom with dead bait on a hook that was much too big for anything that could float itself in that depth of water — or so I thought. A silhouetted caricature of eternal optimism, he fished unconcernedly and with an air about him of leisurely expectancy.

I’d almost reached him when I saw his rod snap into an arc. He fumbled at his reel, then began cranking furiously as he waded backward up the shore. A few moments later he beached a small fish, and I ran to see what it was. The first glance raised my hackles; the fish was a pike — a small one, but unquestionably a pike.

I swung around and looked over the water. Near the end of the jetty was a break in the rocks, and there the placid backwater ended abruptly in a boiling surge as the full force of the outrushing tide drove through. A hunch hit me.

I waded out above my knees and cast my spoon into this caldron. Tensely, I retrieved. Nothing. Another cast, and a third. I was beginning to lose the edge of hope that had spurred me to try again when my spoon was jolted hard. For a split second both the fish and I paused in surprise, then the line sliced off in a tight curve.

I set the drag on the light service reel and struck. The water’s surface foamed, opened up, and a fish was in the air. I had a moment of panic when I saw him, and wondered how much of a beating my slender glass rod and low-test line could take.

I backed up, but line continued to streak off the reel. The fish came out again, this time in a low, greyhound leap.

I backed up, but line continued to streak off the reel. The fish came out again, this time in a low, greyhound leap. I saw him clearly — a big fish, and a snook. After several minutes of surging fight he reluctantly came my way, and when I had him almost at my feet I reached for the gaff on my belt. He spotted me at the same time and reversed his field, stripping line as he ran toward the jagged rocks.

But by then I’d discovered he could be stopped and turned with a cautious thumb. Within a few minutes I gaffed him and lifted my first Texas pike clear of the water. There was enough daylight left for me to admire him — a long, rakish fish with a predatory look about him that was emphasized by his undershot jaw. His tail was broad and his body thick — a 10-pounder, I estimated, as I carried him ashore. Leaving him on the beach, I went back to my position for a few more casts despite the hastening dusk. Within a minute or two I had another pike in the air twice, but he tore the hook out. A third fish struck on the next cast, and he jumped and threw the spoon before I could react. A few casts later I felt a savage strike but couldn’t set the hooks.

The night was rapidly becoming too dark to see where I was casting, and the action had been so furious I hadn’t noticed the twinges of hunger in my middle. But as minutes ticked by without further results, I remembered that the inn’s dining hall would close soon and that I’d have to hurry if I wanted my supper. I happily picked up my one big fish and headed back to report my success to Bill.

He was impressed; he said mine was the largest pike taken that season. After supper I drove back to the point to clean the fish.

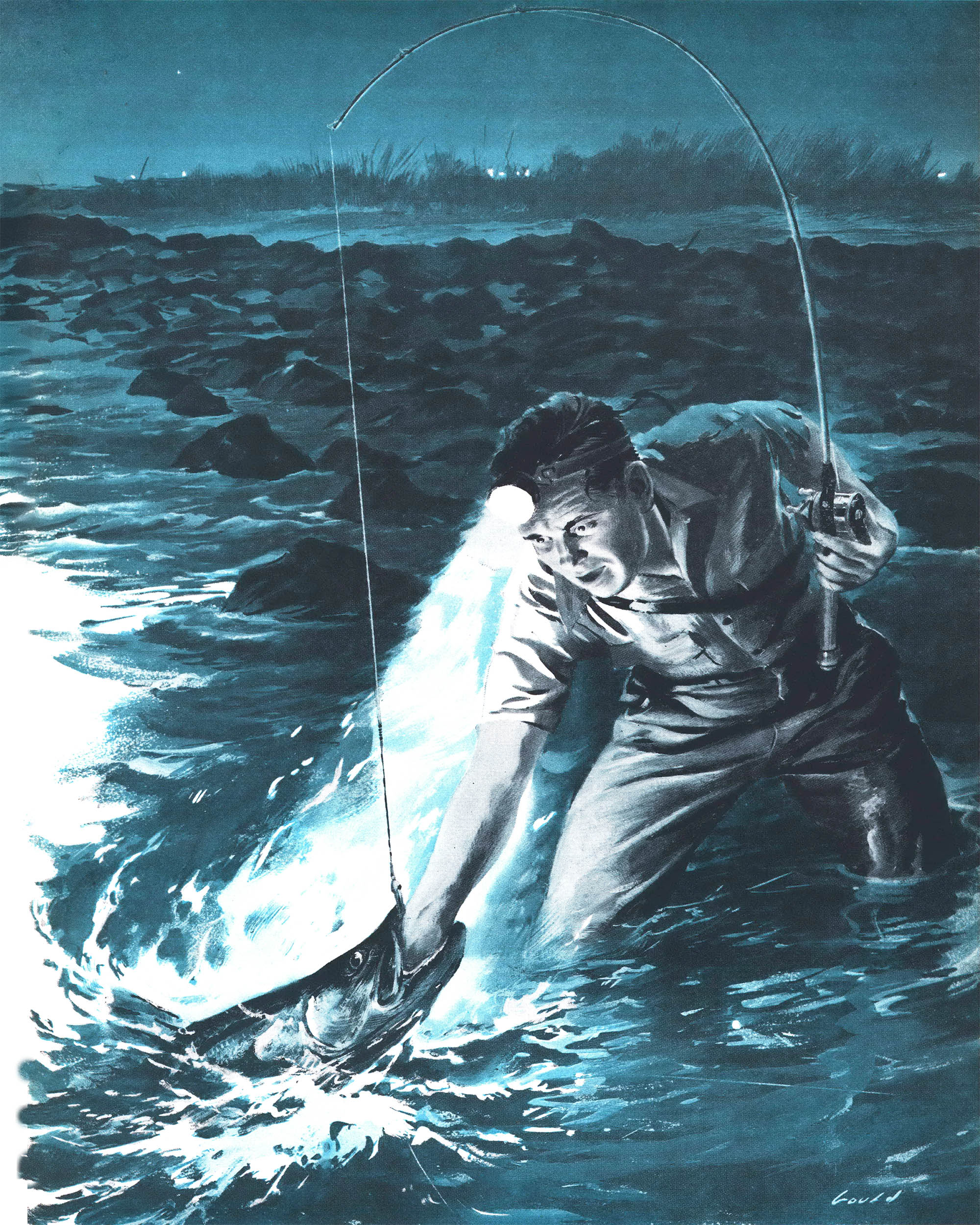

The three-quarters moon had risen and was casting a good light over the point and its surroundings. I squatted at the edge of the water, ready to gut the snook, and looked across the channel. The tide was still racing out, and the same churning eddy lay just inside the break in the jetty. I listened to the tense, subdued rush of water, and imagined that I heard an extra-heavy splash now and then. For a moment I hung undecided, but it was too much for me. Dropping knife and fish, I ran to my car for my gear and headband flashlight. Then I waded thigh-deep into the dark water.

Before I got the first cast out, the beam of my light caught a sousing splash from a feeding fish. I shot the spoon toward it, but I was too eager. I got a backlash. Quickly unsnarling the line, I twitched the spoon loose from the rocks among which it had settled and began a fast retrieve.

I never completed it. Before the lure had moved a dozen feet something tried to tear it off the leader. I snapped up the rod tip and instantly a big snook appeared in the light’s beam, his eyes gleaming red for a moment before he crashed back into the water. But in five minutes I put him alongside my other prize on the beach, and hurried back into the water. The pike were in at last, I was in the middle of the first big run.

Before the lure had moved a dozen feet something tried to tear it off the leader. I snapped up the rod tip and instantly a big snook appeared in the light’s beam, his eyes gleaming red for a moment before he crashed back into the water.

For the next 15 minutes my casts were unproductive, and I relaxed and lighted a cigarette. The solitude of the moonlit scene captured my imagination. I was completely alone. My world was the singing current, the calm night, the backwater’s gentle ripple, the steady blink of the red light atop the beacon tower, and the hungry forms that lurked unseen through the violent eddy.

My peaceful mood was rudely shattered when, on the next leisurely retrieve, the rod was almost torn out of my hands by a ferocious strike. I stood frozen with surprise at the force of the blow and at the power of the fish that was stripping my reel in a screaming run. The cigarette fell from my lips and hissed out in the water.

As the fish bored on, I was sure I’d never land him; my tackle wouldn’t take that much abuse. In desperation I cracked down on the drag and saw the line lift. The rod whipped violently. Then, amazingly, the fish stopped. I waited. I cautiously raised the rod and felt him shake his head. He seemed massive. When I eased off the pressure he ran a few more yards, and stopped again. Then he wouldn’t move, and I couldn’t budge him. My heart sank.

Next the taut line signaled news that turned my despair to desperation. I could feel vibrations from the wire leader sawing gently across the barnacle-encrusted corner of a rock as the fish rode up and down in the wash from the tide. My pike had got through the break in the rocks. I knew that if I let him have another foot of line both he and my spoon would be gone for good.

Doggedly I clamped down on the reel spool and waded sidewise to straighten the leader. Again I hoisted the rod tip. Nothing gave. Increasing the pressure gingerly, I could hardly believe the light line was actually standing the strain. I began to wonder whether the snook had slipped the hooks and left me fighting a rock.

Then he moved. Reluctantly, inch by inch, he came about. A broad tail lifted ponderously, spread and tense, into the beam of my headlight. It swung up and over, and disappeared. The bruiser was coming to me now, allowing himself to be dragged through the water. Could I get him close enough to gaff ?

Now that he was clear of the rocks I handled him with kid-glove tenderness. As a result, he turned suddenly and ripped off line. I grimly thumbed him down, and he stopped. Then I got him turned around and began working him in. Again he shook his burly shoulders and found strength for a run, but it was shorter this time. I eased him back.

At last he lolled on the surf ace and ft was at my knees. I fumbled for my gaff — it was gone from my belt! I looked down at the fish, frantically wondering how I could land him now that I’d whipped him. The spoon was hanging by a thin filament of cartilage in the corner of his protruding lower jaw. It would have torn out if I’d tried to lead him the 30 or 40 yards to the beach, and I didn’t dare give him much time to rest. One healthy flop and he’d be free. I couldn’t gill him — his serrated gill covers were much too big and sharp to risk my fingers anywhere near them. I stood there feeling helpless.

Then the pike’s mouth gaped open. I eyed it for an instant, and did the obvious. Thrusting my fist into that maw, I closed my fingers on anything that furnished a grip. The hook tore out, and the pike revived enough to clamp his toothless jaws on my wrist. At the moment, I couldn’t think of anything that would have felt better.

Read Next: The Unmaking of an Ozark Stream, and One Last, Giant Bass with My Grandpa

I stumbled out of the water and carried the heavy fish far above the tide marks in the sand. I sank to my knees beside him, as wet and almost as exhausted as he. He was mine now. I’d whipped him and the rocks and the fierce tide — on light casting tackle. The battle had lasted nearly 30 minutes.

At the icehouse an hour later, the pike dressed out at 17 pounds. Before I left the point that night I took another, a five-pounder, and the four fish together weighed in at 42 pounds.

It couldn’t happen again, I know. Still, a likely place to find me some night late this summer would be at the point on Mustang Island hankering for another fist fight with those savage, hard-hitting Texas pike.

Read the full article here