We got our first look at the big brown bear under conditions that made a stalk out of the question. It was late evening, and although the May twilight is long on the Alaska Peninsula, there was hardly an hour of good light left.

The brownie was in the open, feeding along the beach two miles away. We’d have to keep out of sight in grass and alders, and long before we could get to him, it would be too dark to shoot. On top of that, an offshore wind was howling down from the mountains, strong enough to blow the feathers off an arrow.

“No use to try,” Ed Bilderback told me. “If we let him alone, we might see him tomorrow.”

The bear looked good through the binoculars, and I itched to go after him. But I knew Ed was correct.

This was the fourth brownie we’d seen in five days of hunting along the bleak, treeless coast of the Peninsula across Shelikof Strait from Kodiak Island. Of the four, three were good trophies; the guides thought one might have been the biggest bear they’d ever looked at. But sighting a trophy and hanging it on your wall are two entirely different matters. I hadn’t succeeded in getting within range of any of the three.

Read Next: The Best Recurve and Longbows, Tested and Reviewed

The hunt had started on Kodiak Island on May 2 last year. My hunting partner was Bob Munger, who runs a hardware store in Charlotte, Michigan. The two of us had just wound up a lively hunt for polar bears on the arctic ice off Point Barrow in April.

Bob and I had met under rather unusual circumstances 10 years before in the deer woods of northern Michigan; we’d sneaked in on the same buck from opposite directions. We’ve been good friends since, but this was the first year we’d hunted together.

Bob had gathered in a fine polar bear, and I had taken one about as good, but I couldn’t claim credit for mine. I’m a bowhunter, earning my living as a manufacturer of archery equipment at Grayling, Michigan. I had driven an arrow into my bear at close range. Given a little time, it would have killed him, but he had other ideas. He charged headlong the instant the arrow sliced into him, and my guide had to put him down with a 180-grain soft-nose bullet from his .300 Magnum. Of course a trophy taken that way doesn’t count in an archer’s score book.

The instant the big brownie went out of sight, Ed raced into the open after him, and I ran for the foot of the rimrock, hoping to intercept him on the far side of the slide. Halfway there, sneaking across over steep and treacherous footing, I heard a low whistle and looked down to see Ed crouched and the bear in plain sight just 25 feet from him.

I had decided to try for a brown bear on the way home. Bob had killed a good brown three years earlier and wasn’t interested in another, but I wanted pictures as well as a trophy. Bob agreed to be my cameraman. He commented somewhat dryly afterward that following a bowman with a camera on a hunt for big bears any reasonable man.

We made arrangements with Bilderback, a Cordova guide, and he met us at Kodiak with his 57-foot boat, the Valiant Maid. He brought along Harley King, also of Cordova, as second guide and helper.

Ed Bilderback turned out to be one of the most interesting and resourceful men I’ve met in a lifetime of hunting. He’s competent at anything he puts his hand to. In his early 30’s, Ed guides in spring and fall, fishes for salmon in summer, and uses the Valiant Maid to deliver mail to a number of native villages on Prince William Sound from October to the end of April. He also has a gold claim back in the interior.

If you were manager of a zoo, needed any kind of Alaska animal, and could get the necessary permit, Ed would fill your order. He’d rope you a bear, sheep, goat, wolverine, or anything else you might want. His basic philosophy is that a gallon of outboard gas will get a fire going much quicker than a quart. He knows brown bears from plenty of first-hand dealing, and understands the problems of a bowhunter because he’s one himself.

He’s also an expert rifle shot, cool and dependable; that’s the kind of guide you need when you’re hunting dangerous game with a bow. I’ve never known a man I’d be more willing to trust to back me, and before this hunt was over I had plenty of reason to be thankful for Ed.

We hunted Kodiak Island for three days without luck. It was a discouraging start for an adventure we’d looked forward to so keenly, but we took the edge off our disappointment by anchoring in Larsen Bay the last day and hiking inland two or three miles to fish the Karluk River.

We planned to cross over to the mainland that night, but Shelikof Strait, separating Kodiak Island from the Alaska Peninsula, was demonstrating why it has a well-deserved reputation as one of the world’s roughest stretches of water. The rumpus was too much for Ed’s boat, so we waited until the wind died at 6 o’clock next morning before venturing out of Larsen Bay. Even then, we had a wretched crossing.

We dropped anchor in a small cove shortly after noon and went ashore in the skiff. Almost as soon as we landed. we spotted two bears just below snowline on a mountain that shouldered up behind the beach. We figured them for a male and sow, and the male was a big bruiser.

We watched them through our glasses for an hour, until they got sleepy in the warm spring sunshine and lay down. Then we started for them, climbing through a tangle of alders. The mountain was steep and wet and slippery from melting snow. and there was still some snow in the alders. It took us 2ó hours to make the climb, and when we got almost up to the bears we ran up against dry, noisy grass. While we were still 60 to 70 yards off, we made enough noise to catch the attention of the big fellow, but we decided later that a flash of sun off the chrome trim of the movie camera Bob was carrying must have alerted him. He raised his head and tried to locate whatever was disturbing his nap, but the wind was in our favor.

He lumbered to his feet and made a small circle, swinging his head, snapping his jaws, and growling softly. His antics aroused the sow from her bed on the point of a ridge about 40 yards from the knoll where he had bedded, and she moved around to the other side and out of sight.

A steep slide, originating at the foot of rimrock about 60 yards higher up, separated the spots where the two bears had been lying. Mr. Widehead, as we named him later — and it fitted him to a T — stood at the edge of the slide and pondered the situation.

He was broadside to me, a perfect rib shot, and the distance was less than 100 yards. A rifleman would have wrapped him up then and there. but I’m not a rifleman. All my hunting in the past 25 years has been done with the bow. I was carrying a 65-pound Kodiak model of my own make and razorhead hunting arrows, a good lethal outfit, but this bear was too far away and the alders too thick to be sure of a killing shot. I’d rather pass up a chance than risk bungling, so we crouched in the cover and watched him until he crossed the slide and rejoined his girl friend.

The instant the big brownie went out of sight, Ed raced into the open after him, and I ran for the foot of the rimrock, hoping to intercept him on the far side of the slide. Halfway there, sneaking across over steep and treacherous footing, I heard a low whistle and looked down to see Ed crouched and the bear in plain sight just 25 feet from him. Ed was hanging tight to his .375 Magnum, and the muzzle was pointed the right way.

Strangely, Widehead had not smelled, seen, or heard us. Intent on following the sow, he stood looking in the direction she’d gone. It was a perfect shot for a bowman except for one small detail — the range was too long.

I started on, but the slide was so steep I couldn’t get a foothold. Now I had to back up, drop down behind Ed, and try again. I was within two or three steps of where I needed to be for a shot when the bear finally winded us and lit out. We never saw him again.

His track in wet snow was 14 inches long, and Ed believed he might have been the biggest brownie he’d ever encountered. Losing him was a bitter pill. We went back to the skiff, cranked the outboard, and followed the shore in an effort to find out where the bear had gone. With our glasses, we could pick up his tracks on patches of mountain snow for several miles, but there was no use trying to follow him. Evidently he’d pulled all the way out of the country.

Disappointed with our luck, we moved to Puale Bay to try new territory. It was dark when we got there, but right after breakfast next morning we started glassing from the boat and soon spotted a bear feeding on the lower slopes of a mountain across the bay. We watched him for an hour, until he lay down about one third of the way up the mountain. Then the four of us piled into the skiff and headed for him.

He was a wise one, and we should have been more careful in our approach. He picked up the noise of the outboard while we were a mile or more away, and he didn’t like it. As we crossed the bay, we could see his head rise every now and then. He was keeping an eye on us. When we ran in on the beach, he got to his feet and moved off up the mountain.

About one third of the way from the top, he lay down again on a patch of snow, but stayed alert and restless. Before we could climb anywhere near him, he moved again, slogging up through the snow and topping over. We took the skiff around into the next cove, to save ourselves a long hard climb, but the area was rough and broken. We couldn’t locate him again.

A strong northwest wind came up that night, blowing 50 to 60 miles an hour, and when the pounding of the boat woke us up at 4 a.m. the anchor was dragging. Ed and Harley winched it up, and we moved closer to the beach for shelter. While they were maneuvering, the line that held the outboard skiff astern snapped, and the wind swept the skiff swiftly toward the open sea.

The outfit was worth at least $1,000. We had a second skiff lashed on the afterdeck and a spare motor in the hold, but there wasn’t time to break out the motor. We got the skiff into the water, battling wind and waves, and Ed buckled on a life preserver, the first time we’d seen him take that precaution. He jumped into the skiff with a pair of oars and a bailing pail.

Watching him, lost to sight most of the time in great troughs. we figured the odds were poor that he’d make it. We finally saw the drifting skiff washed ashore, swamped, and pounded savagely. Ed ran his boat up on the beach near it. He abandoned the motorless skiff and fought for what seemed like hours to bail the other one and get it afloat. Time after time, before he could get the motor started, the seas smashed him back onto the beach and buried the boat under foaming water.

We watched helplessly from the deck of the lurching Valiant Maid; I was beginning to wonder whether Harley and Bob and I could navigate her back to Kodiak and whether Ed could keep from freezing until we could send a plane back to pick him up. Then we saw a wisp of blue smoke from the outboard. Bow spray flew up as the skiff knifed into the seas.

l don’t think I’ve ever been more relieved than I was when we hauled Ed over the rail at last, blue with cold and water streaming off him from head to foot. He’d saved his skiff and motor, but I’m. still not sure it was worth the risk. We never found the other skiff, and we assumed it was blown out to sea.

We lost two days then without seeing a bear, partly because the wind continued to blow a gale. Ed shot a few hair seals for the $3 bounty and the livers, which are a real delicacy. I was knocking off a rabbit now and then with a blunt arrow, and we dug razor clams at low tide and kept traps down for the giant king crabs found along the Alaska coast. We were living like kings and enjoying every minute, but we had allowed only a little more than a week for the hunt, and our time was running out. I was beginning to despair of getting within bow range of a brown bear, and after what had happened with the polar bear on the ice off Point Barrow, I didn’t relish going home from this hunt without a trophy.

To make matters worse, I kept lamenting the wrong decision that had cost me a magnificent trophy that first afternoon on the Peninsula. If only I’d followed Ed across the slide instead of going higher under the rimrock! The bear we called Widehead had been all any hunter could ask for, and from where Ed had confronted him, at 25 feet. it would have been easy to put an arrow all the way through him.

We decided we might change our luck by moving again. Early in the evening of May 9, we anchored in Wide Bay, opposite the extreme southwestern end of Kodiak Island, and went ashore in the skiff to look around. We were no more than on the beach when we sighted the bear I mentioned at the start of this story. Reluctantly we decided it was too late and too windy to go after him. We’d have to hope for better luck the next day.

The wind raged all that night and through the next forenoon, making it useless to go ashore. It dropped at noon, though, so we landed for a look at the country. We waded across a lagoon and climbed above the alders. and when Ed looked back toward the beach a fair-size brownie was feeding within 100 yards of the skiff.

Right then we couldn’t figure how he’d shown up so quickly, but later we found his bed behind a tangle of driftwood just above high-tide mark. The wind had kept him from hearing us come ashore.

He wasn’t big, but he was better than no bear at all, so we turned back. He didn’t stay put long enough for us to catch up, however. He kept moving along the beach, toward a mountain that broke off into the sea to form one end of the bay. Finally he climbed it and went out of sight. We took the skiff around into the next cove, spotted him halfway down the mountain, went back on shore, and spent the rest of a hard afternoon hiking· and climbing in hip boots. We couldn’t make contact.

Brush had been freshly torn up and ripped apart, and some of the beds — flattened and as big as a dinner table — looked recently used. A bear bed of that size gives you a creepy feeling. I also felt, however, that this brown might be exactly what I had hoped for. Certainly no small bear had made such beds.

We got back to the boat at supper time, tired and discouraged, ate a snack and went ashore once more. We had barely beached the skiff when our big brown of the previous evening walked out of the alders at almost the same spot, about two miles away.

We called a brief huddle. It was too late in the day for pictures, and too late in the hunt to take chances on anything that might upset the applecart; we decided our camera crew, Bob and Harley, would sit this one out. They chose a high observation point where they could watch the show and Ed and I started for the bear.

What we did at first could hardly be called the stalk. A jumble of driftwood bordered the high-water line. From it tall grass ran back 100 yards to the edge of the hills. A quarter of a mile on our side of the bear, an alder thicket replaced the belt of grass. The bear was about 20 yards out from this thicket, on the open beach. The wind was blowing in from the sea, and the low evening sun was at our backs. Everything was in our favor, and we simply walked toward him, following a band of firm, wet sand left uncovered by the receding tide.

Here was a bowhunter’s dream: a bear unmolested, wind and sun exactly right, waves washing up on the beach to drown out any noise we might make, and alders to provide cover right up to ideal bow range.

We had to hurry, because of approaching darkness. Luckily we had changed our hip boots for leather footgear before coming ashore. Ed paced ahead, and I liked the way he carried his sawed-off .375. You can tell whether a man can use a gun by the way he handles it. I was carrying a Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum revolver in a shoulder holster, a standard precaution of mine when I’m hunting dangerous game. It’s a heavy handgun, but now, for the first time on this hunt, it felt feather-light.

The bear went on feeding, completely unaware of us. Near the alders, our real stalk began. We eased over behind the driftwood and entered the thickets on a well-used bear trail.

It was quickly apparent that bears hung out regularly in the alder patch. The thickets were full of trails and beds, and the place actually smelled of bear. Brush had been freshly torn up and ripped apart, and some of the beds — flattened and as big as a dinner table — looked recently used. A bear bed of that size gives you a creepy feeling. I also felt, however, that this brown might be exactly what I had hoped for. Certainly no small bear had made such beds.

Alaska’s alder tangles are as tough to get through as any brush I’ve ever encountered. The weight of winter snow flattens the trunks while they’re still small; they grow horizontal, close to the ground, for a yard or two, then turn upward and reach a height of 10 or a dozen feet. The result is something like a mammoth, ragged fishnet. The only worse going I know of is in the devil’s-club thickets along those same Alaska streams.

But Ed and I weren’t making out too badly in this alder patch. We found a bear trail paralleling the beach, only a short distance in from the edge, and when we stepped into the open the brownie was just 50 yards off. He was facing away from us, pawing over a pile of kelp.

That first look at such close range should have told me I was dealing with an extraordinary bear, and maybe it would have if I’d been more experienced in judging them. But to me he looked like no more than average size. True, his body was impressively long and bulky, and his head seemed small by comparison — both good signs. But I didn’t guess his real size, nor did I waste much time wondering about it. My work was cut out for me, and it didn’t include speculating on how big he was. I learned years ago that the handicap of hunting with a bow calls for careful but prompt analysis of critical situations, and leaves little time for admiring trophies until they’re dead.

Ed and I, screened by driftwood and brush and concealed by our camouflage outfits, studied the big brownie for a few seconds. I realized that from here on, it was up to me. Everything had gone perfectly so far. If I fumbled, I’d have no excuse.

Ed said softly, “What do you want to do?”

I didn’t waste words. “Get closer,” I said.

His answer was equally brief, and to the point. “Go ahead,” he told me.

It wasn’t much of a speech, but it shook me to the toes. For no reason at all, there flashed through my mind a trivial scrap of information I knew about the Yana Indians of northern California. They have no word in their language for goodbye. Instead they say, “You go, I stay.” It hit me forcibly that Ed’s calm, “Go ahead,” meant exactly the same thing.

Actually, I didn’t want to get any closer to that brown. I was already too close for peace of mind. But I was here to kill a bear, this was plainly a good one, and in bowhunting 25 yards is more than twice as good as 50. I had no choice, and I knew it.

I slid the .44 Magnum out of its holster and stuck it in my belt, where it would be handy. Then I stooped and crawled ahead, partly hidden behind the rim of driftwood, until I was between the alders and the bear. When I stopped, we were just 20 yards apart. I waited on one knee for a broadside shot, and out of the corner of an eye I saw that I was beside the trail he’d used to go out to the beach. In all likelihood he’d use that same trail to get back to cover when my arrow sliced between his ribs.

I realized now that I was facing a bigger than average brown. He was so close that I could watch the wind ruffle the pelt across his burly neck, make out his long claws, and size up his bulk and weight. No matter how long I live, I’ll never forget the thrill of those few seconds while I waited with my arrow on the string, ready for the draw. I can shut my eyes now and see the whole scene: the black volcanic sand of the beach, the sea reddened by the westering sun, and the bear standing, blocky and huge, over a pile of brown kelp washed up by the surf.

There are riflemen who deplore bowhunting for game that’s as dangerous as the brown bear, and others who criticize the bowman for getting into situations where he needs a rifle to back him up. I have an answer. If you want a trophy the easy way, take it with a rifle at 100 to 200 yards. But if you’re looking for the ultimate in thrills, go in and take your bearskin rug with an arrow at 60 feet. As for being backed, no hunter in his right mind is going to tackle a brownie with a bow deliberately unless he has a rifle behind him, in the hands of a man he can count on.

The bow is a lethal weapon for game of any size. But every archer knows that no arrow, no matter how well placed or what the power of the bow behind it, can be counted on to kill instantly. Death, except in rare cases, comes from bleeding, and that takes a bit of time. What I was wondering now was what would happen after I drove my arrow into this big brute and before he died. I was face to face with what, in the bull ring, they call the moment of truth.

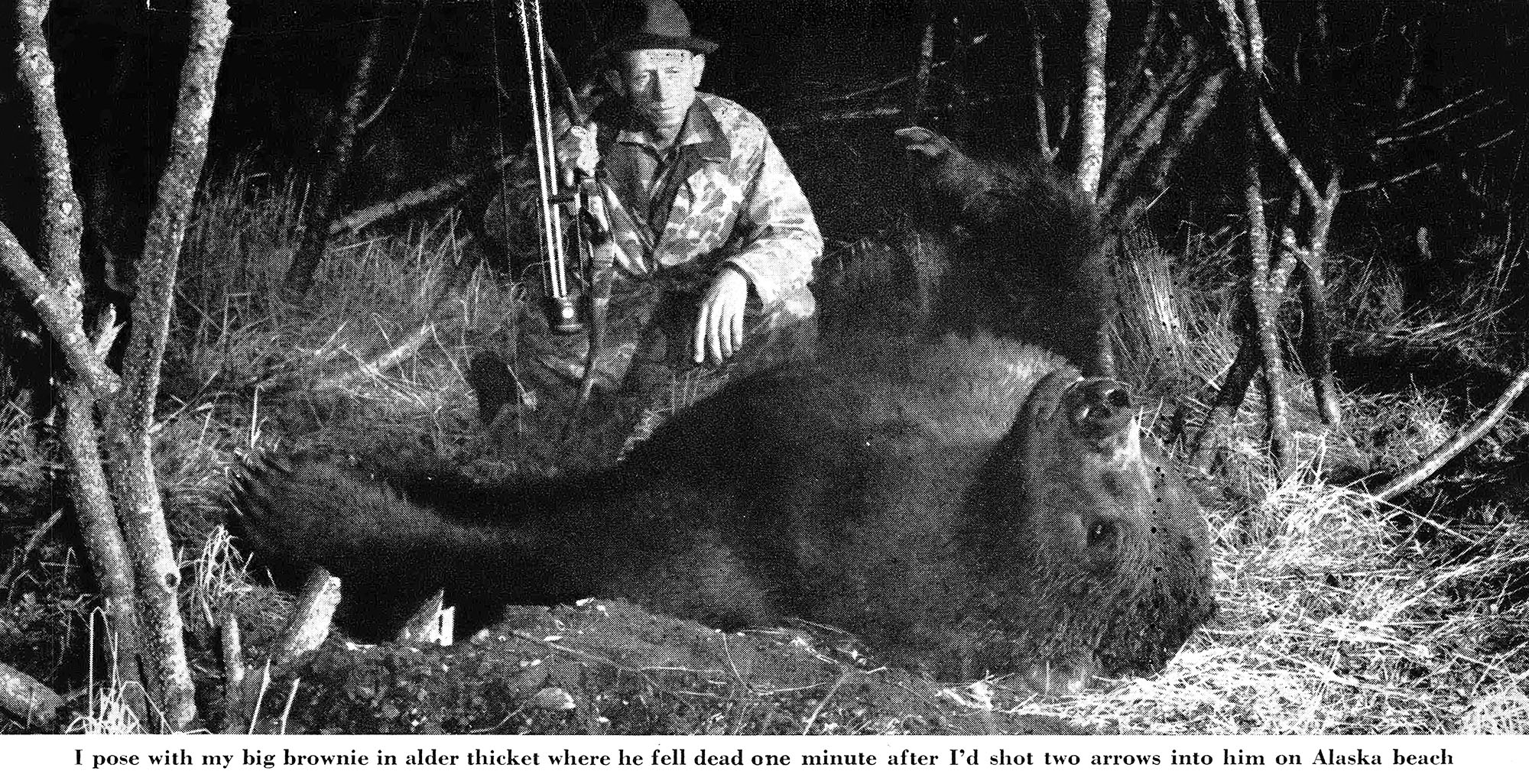

The bear, still not suspecting I was there, turned broadside to me. I loosed my arrow and saw it bury to the feathers well back in his rib cage, in the liver area.

He let go a horrible growling roar and spun round and round, biting at the end of the arrow. Before he’d made more than three or four turns, I had a second arrow on the string. He started my way and I shot head-on, but the razorhead lodged against heavy bone in a foreleg, doing no damage at all.

The bear was less than 30 feet away, and I’d begun the trigger squeeze when Ed’s voice boomed out from somewhere behind me, “Don’t shoot! He’s a big one!”

Coming for me at top speed, that huge brown was an awesome sight. He rolled like a bulldog, with bowlegs and turned-in toes, but he covered ground like an express train. He wasn’t charging, for up to that time he had no idea what had happened or where the trouble was. He was just following his usual trail back to the alders, but I happened to be crouched beside it, and when he got close enough he couldn’t fail to see me. I had the .44 revolver in my hand without knowing I’d reached for it. In practice beforehand, I’d been able to move a lot of lead with satisfactory accuracy, shooting rapid fire, double action. Right now seemed the time to put my training to the test.

The bear was less than 30 feet away, and I’d begun the trigger squeeze when Ed’s voice boomed out from somewhere behind me, “Don’t shoot! He’s a big one!”

It sounded contradictory, but I knew instantly what Ed meant. A bowhunter can’t claim as a trophy any animal that shows a bullet hole. If I hammered a .44 slug into this brown, my license was filled, the hunt was over, and I’d be going home with nothing to show for it. What Ed was saying was that I had a good hit in a big bear, and let’s not get any lead in him. Or interpreted another way, he meant, “Put that pistol down I’m handling this.”

I recalled, in a flash of thought, his theory that a gallon of gas will start a fire quicker than a quart. In the showdown, he could do a surer job with his .375 rifle than I could with my .44 pistol. I took his advice. I didn’t lower the handgun, but neither did I complete the trigger squeeze.

What happened next was the last thing I expected. When the bear heard Ed’s voice, he knew for the first time what had hurt him and where it was. In the same instant, he sighted me. We measured later from where I was kneeling behind the pile of driftwood to his claw marks on the trail. The distance was only five paces. By all the rules, he should have been on me in a couple of jumps. But for some reason, maybe because by that time he was a very sick bear, he veered off the trail at an angle and ran headlong into the alders.

The instant the big brown was out of sight Ed took off through the brush and up the side of the mountain for a better view. I followed at an easier pace, detouring around the area where I thought the bear might be. When I got up to Ed, he was holding his binoculars on a dark object down in the thickets. We studied it and made out a front foot of the bear, sticking up between alder trunks. We watched for quite a spell, but it didn’t move; we concluded our brownie was dead.

Outdoor Life

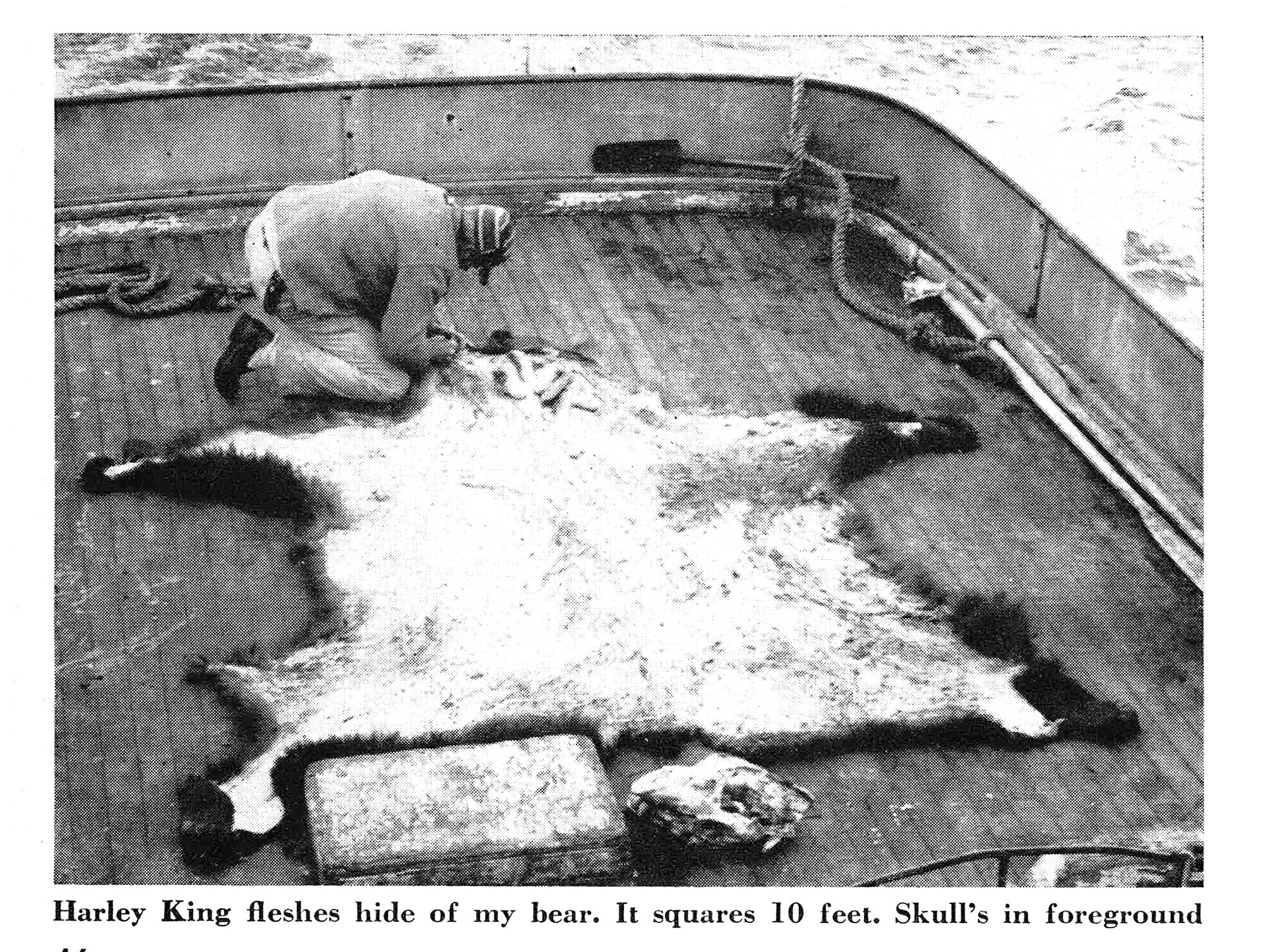

We hurried down and found him stretched flat on his back with all four feet in the air. The razorhead had sheared off a rib on the way in, sliced through the liver, and lodged against a rib on the other side. Blood had poured out of him by the bucketful, and he’d left a trail that a man could almost have followed blindfolded. He had run 200 yards and lived less than a minute after the arrow hit him, but it was a minute I’ll remember the rest of my life.

Read Next: The Best Bear Defense Handguns

In that minute I had killed the biggest brown bear ever taken with bow. His pelt squared 10 feet, and his skull scored 28 (length of skull without lower jaw, plus width of skull-in I inches) going down as a world record on the list of the newly organized Pope and Young Club, which from now on will keep score on trophy game taken by bowhunters.

I have the full mount in my trophy room at Grayling. It’s pretty impressive, and I can’t, look at it without remembering Ed’s casual, “Go ahead,” when I told him, there at the edge of the alders that I wanted to get closer, and thinking of the Yana phrase of farewell, “You go, I stay.” I couldn’t have had a better man behind me, but for a second or two I’d gladly have stayed and let him go in my place.

Read the full article here