This story, “In the Jaws of the White Bear,” appeared in the April 1976 issue of Outdoor Life.

The Boothia Peninsula is the northernmost point on the mainland of North America. It was there, in July of last year, that a research team of the Canadian Wildlife Service captured a 420-pound polar bear as part of Canada’s continuing study of its polar-bear population.

The men subdued the bear with an immobilizing drug, weighed it, marked it for identification with black dye in the fur of the back, and recorded the desired information about it. In recent years that procedure has become routine in bear studies all over this country and Canada.

When the job was finished and the bear had recovered from the effects of the drug, the researchers watched it walk away, wondering whether they would ever hear from it again.

That was destined to happen, and under circumstances they could not possibly foresee.

Meanwhile, on the north shore of Somerset Island, some 200 miles north of where the bear had been captured and marked, a geological-survey party of eight — seven men, and a young woman recently graduated from college, who was doing the cooking was camped in one of the bleakest places off the coast of Canada’s Northwest Territories.

The camp consisted of seven tents set in a rough circle. I was one of those men.

Somerset Island is one of the most desolate places in the Canadian Arctic. None of the arctic islands have trees, but most of them are green with moss, grass, and dwarf willow that grows a few inches above the ground. Many are made colorful in summer by a profusion of wildflowers that bloom with startling suddenness in the unending daylight. But not Somerset. It is a barren place of limestone shingle, with drifting ice forever in sight just offshore. There is lit tle fresh water and less food for a bear in the barren interior of that big island.

Our crew was studying beach erosion and ice movement for the Geological Survey of Canada. With the exception of Bob Taylor, chief of the party, we were college students doing graduate work, or just out of college. I was 23, working on my master’s degree at McGill University. The others were all in their 20’s. Bob was a full time employee of the Geological Survey in Ottawa. At 27, he had spent six summers in the high arctic.

Our job had nothing to do with school. Again with the exception of Bob, we had hired out for the sum mer of 1975 because we wanted the income. It had proven a lonesome job. We had seen almost no one except the members of our own crew.

We had begun work on June 23. We were due to leave at the end of August, and we were looking forward to getting back into human society. To tell the truth, by the end of summer some of us were getting a bit homesick.

On top of that, there had been a time when fresh meats and vegetables ran low and replacements that were supposed to be flown in failed to come. We were on a monotonous diet of canned roast beef and ham for many days.

That situation improved dramatically, however, when Suzanne Costaschuk flew in and took over the cooking. She brought fresh food, spices, and other items we had been doing without, and our meals picked up. Suzanne was from Ottawa, starting work on her master’s degree. She also brought with her a 10-week-old German shepherd pup named Mitzi.

In those high latitudes there is no darkness through the summer. By late August the sun was setting about midnight, but it did not drop out of sight. About half of it showed as a bright semi-disc moving along the southern horizon, and there was ample light to read by all night long. We had adjusted to the daylight nights, however. By the time we turned in, we were tired enough to sleep, light or no light.

About 2:30 a.m. on Tuesday, Au gust 19, I was awakened by a scratch ing noise outside the sleeping tent occupied by Ross Cameron and myself. At first I thought it was only the wind, which often blows hard on that desolate coast. But after a minute or two Mitzi, tied to a stake outside, began to bark furiously. Ross and I realized we had an intruder.

An arctic fox had prowled into the camp several times, sniffing around the tents. Our first thought was that the fox had come back and that the dog, staked out that night for the first time, was resentful.

“I’ll scare it off,” Ross said, and stepped to the opening of the tent. Next he yelled, “It’s a polar bear!” During the whole summer we had seen only one polar bear, on June 24, and some tracks, both a long way from camp.

Ross and I had no gun in our tent. There were three guns in camp, all bolt-action .30/06 rifles. Two were in other sleeping tents, the third in the kitchen tent.

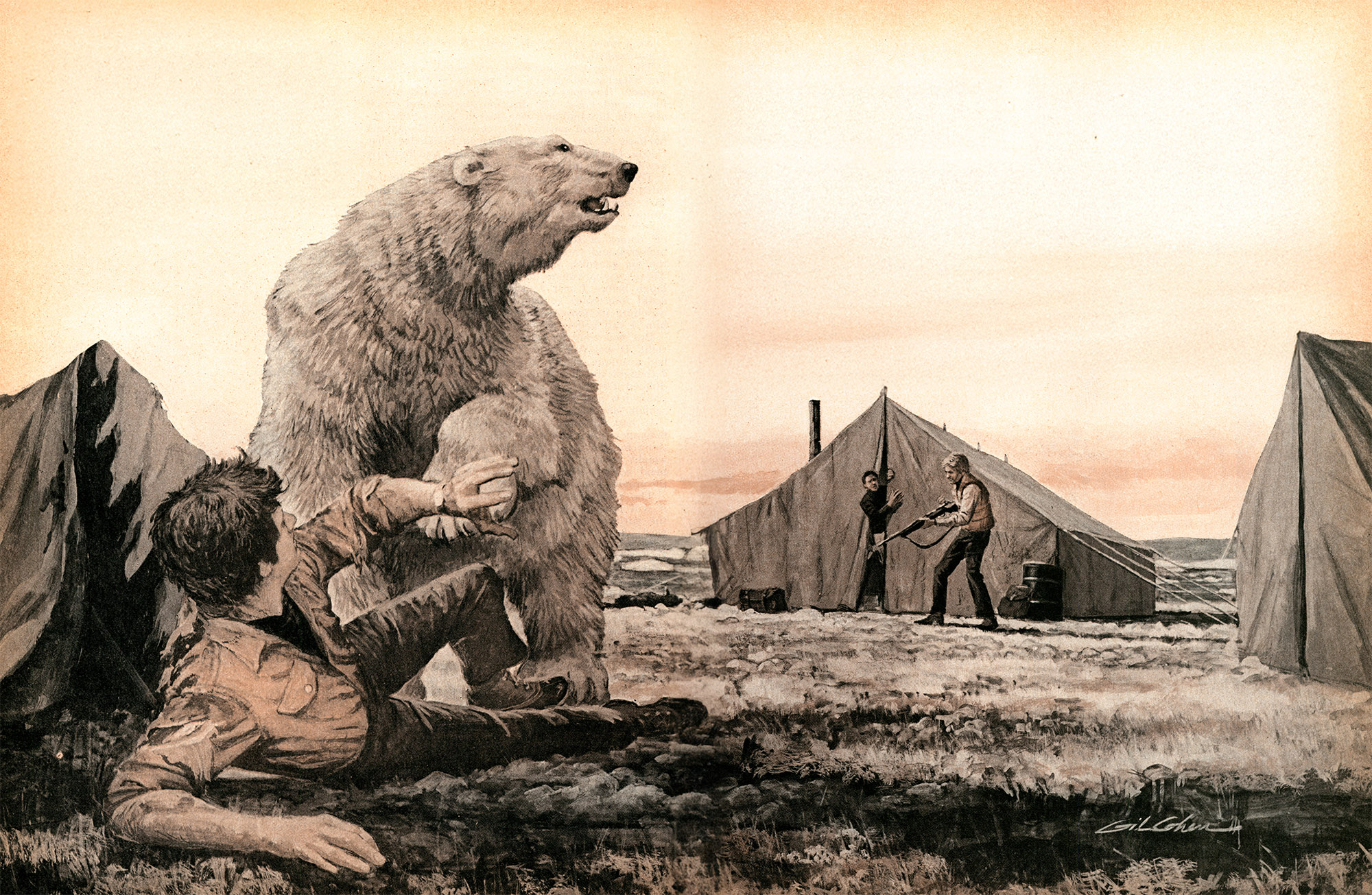

“I’ll get the rifle,” Ross barked. He disappeared, running for the kitchen tent, and I ducked out of our tent to back him up. But I brought up short. A magnificent white bear was standing just 10 feet away, waiting for me, and looking at me with a hard and hostile stare.

My first thought was, “What a beautiful animal.” Then it flashed through my mind that we must get rid of him.

Mitzi was still jumping around on her leash, still barking angrily. I saw that she had been badly clawed or bitten, and I realized we were dealing with an enraged and dangerous bear. We learned later that for no apparent reason it had already torn up our two inflatable rubber boats. Be cause it didn’t like the man smell on them? Who can say?

I spread my arms as wide as I could and yelled at the top of my voice. The bear leaped for me as if a spring had been released. On the way he brushed the tent, ripped up its stakes, and tore a big rent in the canvas. Then he was on me.

He didn’t rear erect or use a fore paw to belt me down. Instead he seemed to push me over with his weight. Almost before I knew what was happening, I was on the ground and he was standing over me. He grabbed me by the head, and I felt myself being dragged along on the ground. Far worse, I felt his teeth raking my scalp.

Strangely enough, I had felt no pain — only the sharp realization that I was going to die, accompanied by something close to resignation.

I was powerless to fight him off. I tried to turn my head away and protect it with an arm, but that seemed to do no good at all. I could see blood on his paws, I suppose from the dog Mitzi.

Strange thoughts go through a man’s mind at a time like that, and they go through like forked lightning. My first was that the whole thing was a bad dream, that it wasn’t really happening. Then I knew it was no dream, and I thought of my parents and how saddened they would be if I died there in the arctic. I thought of friends I’d never see again. And all the while I waited for the bear to crunch down on my skull. I waited for the death bite. The last thing I remember thinking was that if he crushed my head and I lived, I’d be no better than a human vegetable. Then he was gone.

My ordeal had lasted no more than a minute or two, although it seemed much longer than that. I doubt that anything as dreadful will ever hap pen to me again in my lifetime. Strangely enough, I had felt no pain — only the sharp realization that I was going to die, accompanied by something close to resignation. I read once that an attack by one of the big carnivores overwhelms the human nervous system and leaves the victim immune to pain, and apparently that is true. Certainly it was in my case, for the bear had given me a savage working over without my feeling any real hurt.

By that time Bob Taylor and his tentmate Jim Savelle had taken a hand. Bob had seen polar bears come into a camp before. When he and Jim woke up to the sound of screams and growls, he knew instantly what was happening. They looked out, couldn’t see me, but heard me screaming under the bear.

The two men kept a rifle handy in their tent. Jim grabbed it, and Bob ran for the kitchen tent to get the gun there. Ross Cameron already had it out of its case, and he thrust it into Bob’s hands. Bob stepped out, leveled the rifle, and pulled the trigger. There was no shot. The firing pin fell with a useless click.

Bob will never be entirely sure what happened, but he believes that in his haste and excitement he had failed to pull the bolt of the rifle back far enough to move a cartridge into the chamber.

“When I ran into the kitchen tent,” Bob says, “the bear was mauling John on the ground, about 50 feet away. My only thought was to get him off. When I came out, I dropped my eyes for a second to load the rifle, and when I looked up the bear was coming for me, maybe 20 feet away, although it didn’t seem more than 10.”

Bob tells the story of the attack this way:

“He didn’t knock me down. He reached up, still on all fours, put front paw on my shoulder and pushed me over. I swung the barrel of the rifle as a club, aiming for his head, but he was coming too fast. He dodged inside the blow, and it landed harmlessly on his shoulder. Then I was on the ground, and he had me by the back of the head.

“I doubt that he was on me much more than 30 seconds, certainly not more than a minute, but it seemed like an eternity. I kept trying to get my head away from him, and he kept going for the back of it. I could feel and even hear his teeth scrape across my skull, and I waited for the final crunch. It is well known that a polar bear usually kills a seal by biting several times about the back of the head and back. Apparently this one intended to do me in the same way. But the human skull is a bit too big for the jaws of a bear to get a good grip on, and it’s hard enough so that it doesn’t crush easily.

“He dragged me a few feet, dropped me, got a fresh hold, and dragged me again. All the while I was trying to swing the rifle, trying to knock him away, with very little, luck. He must have resented that finally, for he bit deep into my right shoulder and put it out of action. I could no longer manage the rifle, and I thought to myself that the attack was as good as over. I had no doubt that he’d kill me.”

The bear was now 50 or 60 feet away, dragging Bob out of camp. Savelle couldn’t shoot, for fear of hitting Bob.

In the meantime Jim Savelle had run out of his tent with the rifle kept there, loaded and ready. The bear was now 50 or 60 feet away, dragging Bob out of camp. Savelle couldn’t shoot, for fear of hitting Bob. He held his fire until Bob’s arms, legs, and body were out of the way. Then he fired at the bear’s shoulder.

Bob heard the shot. The bear let go of him, and its head jerked up. Instantly Jim put a second shot into the head. We learned when it was skinned that the first shot had killed it, ranging up through the shoulder and severing the spine in the neck. The bear was dead on its feet when the head shot hit. That one also would have killed instantly. Jim Savelle had done a cool job.

Bob scrambled erect and tried to run.

“I didn’t get far,” he said after ward, “but I didn’t lose any time doing it.” Jim helped him into the kitchen tent. Like me, he had felt no pain at any time.

I was already out of the action. As soon as the bear let go of me I had struggled to my feet and run for the kitchen tent, where I tried to radio Resolute Bay for help. On the way I passed the bear almost close enough to touch, and I saw odd-looking black stains on its back.

The whole attack had lasted hardly more than two or three minutes, but it had left two of us severely torn around the head and shoulders, and the puppy Mitzi bitten in the neck so badly that she had to be put down.

Suzanne was one member of the party who had taken no hand. She had started to come out of her tent but thought better of it, which was probably fortunate for her. I believe that with all of us running around, the bear would have gone for any body it got its eyes on. Apparently it had failed to notice Jim Savelle.

It was small as polar bears go. In fact, Bob Taylor remembered that while it was moving toward him the thought had gone through his mind that it wasn’t a very big bear. That was confirmed when the Canadian Wildlife Service reported its weight at 420 pounds.

Someone suggested later that in all likelihood we were the first humans it had ever encountered, but of course that was not true.

We were greatly surprised to learn about the wildlife researchers who had captured and marked the bear only a month before on the Boothia Peninsula, directly to the south of Somerset Island. That accounted for the black marks I had seen.

To reach our camp, the bear had traveled an airline distance of close to 200 miles in a month. The way the animal had come, it had probably been quite a bit farther than that. It’s my own belief the bear probably had walked and ridden drifting ice north along the coast of the island. Its stomach was full of seaweed.

That is one of the common foods of the polar bear, but he turns to it only when he is unable to get meat. Seals are his mainstay, so long as he remains on the drifting ice. On land, the arctic islands offer him slim pickings, hardly more than lemmings, birds and their eggs in summer, and an occasional dead seal or whale that drifts up on the beach.

We do not believe that the bear that came into our camp was driven by hunger, but it may well have been hungry for meat. Polar bears are notoriously unafraid of man. If any thing was needed to send this one into blind rage, the encounter with Suzanne’s dog would have done it.

nd if we had felt no pain when the bear tore at us, that certainly could not be said for the stitching job. The doctor used no local anesthetic, and, in my case at least, every stitch hurt like blazes.

Our encounter had happened shortly after 2:30 a.m. At that hour few radio stations are on the air in the arctic, but we were lucky. A Polar Continental Shelf Project radio operator in Tuktoyaktuk was monitoring his set, and he picked up our May day signal at once. He contacted the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and

in a very short time a Twin Otter aircraft, piloted by Lorne Bradley, was on the way from Resolute Bay. Within two or three hours after the attack we were in the Resolute Bay Nursing Station. A Dr. Braganza from the icebreaker Louis St. Laurent flew in by helicopter to treat us.

The medical diagnosis of our injuries was “multiple lacerations” on the head and back for both of us. That doesn’t quite tell the story. What we had were deep jagged cuts, inflicted by the bear’s teeth. It had not used its claws to do any serious damage. Each of us had more than 10 cuts that required sutures to close. I still don’t know how many stitches it took. The wounds on my back showed the width of the bear’s paws at over 10 inches.

And if we had felt no pain when the bear tore at us, that certainly could not be said for the stitching job. The doctor used no local anesthetic, and, in my case at least, every stitch hurt like blazes. I can still hear him say, “Got to take one more,” and I’d grit my teeth and wait for the curved needle. The treatment was far worse than the mauling.

But the work was well done. That evening we were flown by regular jet to Frobisher Bay, on the south end of Baffin Island some 500 miles to the southeast, and hospitalized there. Not many years ago Frobisher Bay was no more than a name on the map. Now it is a bustling community of 2,400 people.

We were in the hospital four days, leaving for Montreal early Sunday morning, August 24.

Both of us made a complete recovery. The attack left no lasting injuries, and we were able to return to our normal pursuits. Bob couldn’t use his right arm for a few weeks, a result of the deep bite in the shoulder, but before the end of the year it was as good as ever. All that remains now — less than nine months after the attack, as this magazine reaches newsstands — are scars and memories.

Read Next: I Was Mauled Over and Over Again by a Grizzly. I Should Have Died

No, that is not quite all that remains. We will always carry a feel ing of deep gratitude to our camp mates for the way they kept their heads and did the right things.

If it hadn’t been for Bob Taylor, I would not be here today. And if it had not been for Jim Savelle, Bob wouldn’t be here either.

Read the full article here