Kelly’s Ford, on the Rappahannock River in Virginia’s bucolic Fauquier County, is best known as the site of a bloody battle of the Civil War. Today, in a testament to the resilience of both the American people and the land they love, outdoor enthusiasts of every stripe—from walkers and joggers to anglers and paddlers—frequent the nearby CF Phelps Wildlife Management Area (WMA), just minutes from the historic battlefield. On this day, however, a group of outdoor lovers had convened at the WMA for an entirely different purpose: Nearly a dozen men, women, and children from the Mid-Atlantic Chapter of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers (BHA) had gathered to take out the trash.

Each year BHA members participate in the “Great Packout,” a nationwide program in which American hunters and anglers collect trash from nearby public land. How much of a difference can a few people make in a few hours? The answer is that when a few people gather for a few hours on public lands all across the country, they can accomplish quite a lot.

Among the diverse, stalwart crowd were former soldier and avid hunter Allen Jackson and his 12-year-old daughter Katie. “We deer hunt this area from time to time, and I feel like if we use it, we have an obligation to help out.” And why was Katie ready and eager to work on a Saturday morning? “I like being with my Daddy,” she replied sheepishly.

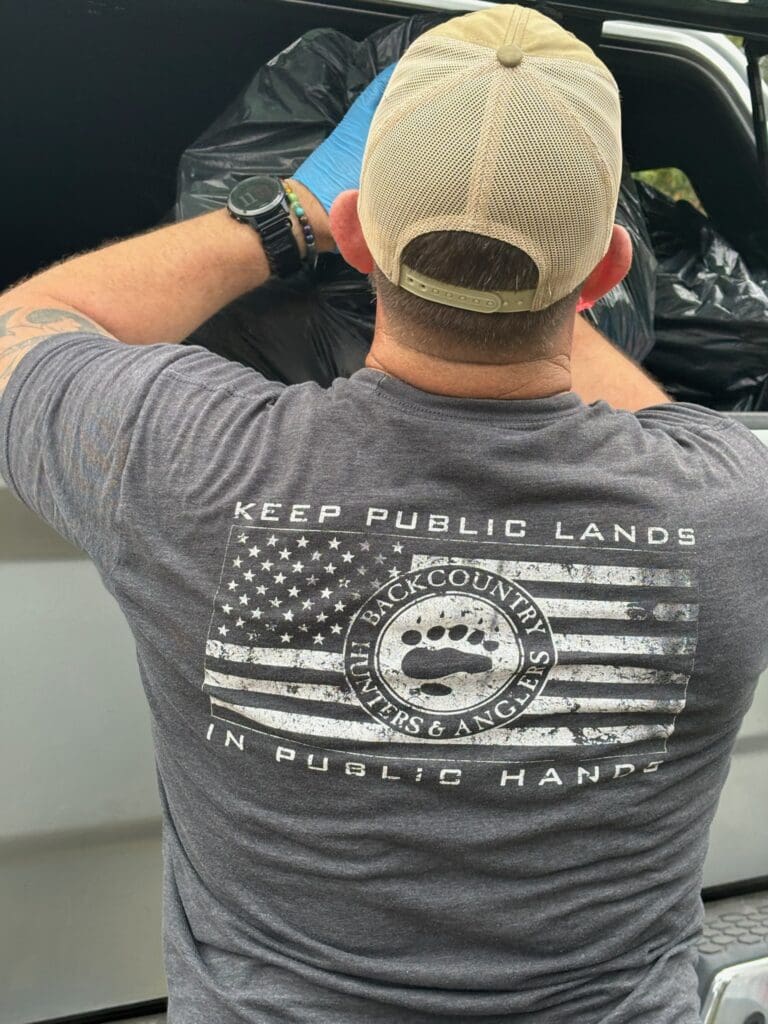

Garrett Robinson, a 26-year veteran of the Marine Corps and vice chair of the Mid-Atlantic Council of BHA (representing Delaware, Maryland, the District of Columbia, and Virginia), began the packout with a general orientation and a safety briefing. Wearing a gray t-shirt that read “Public Land Owner,” Robinson stood behind his pickup truck bearing water bottles and boxes of donuts for volunteers. “It sure is good to see everyone this morning,” he said with a broad smile. “How many of you were here last year when we did this cleanup?” A few hands went up. “I so appreciate that you came back. Your experience will help out this morning.” Robinson briefed volunteers on the day’s plan and stressed personal safety. “Keep your eyes and ears open, and please watch out for the person next to you. We’ll be picking up trash along the road, so we need to be vigilant.” Divided into teams and assigned specific focus areas, volunteers received their weapons: plastic gloves and trash bags. Teams set out to conquer and report back.

“We do our best to pick up as much trash as we can,” commented Jonathan Petri, a Wildlife Area Manager for the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, “but honestly, sometimes it seems like a losing battle. Folks showing up, willing to help? It’s gratifying. And it ensures that the area remains healthy for hunters and anglers.”

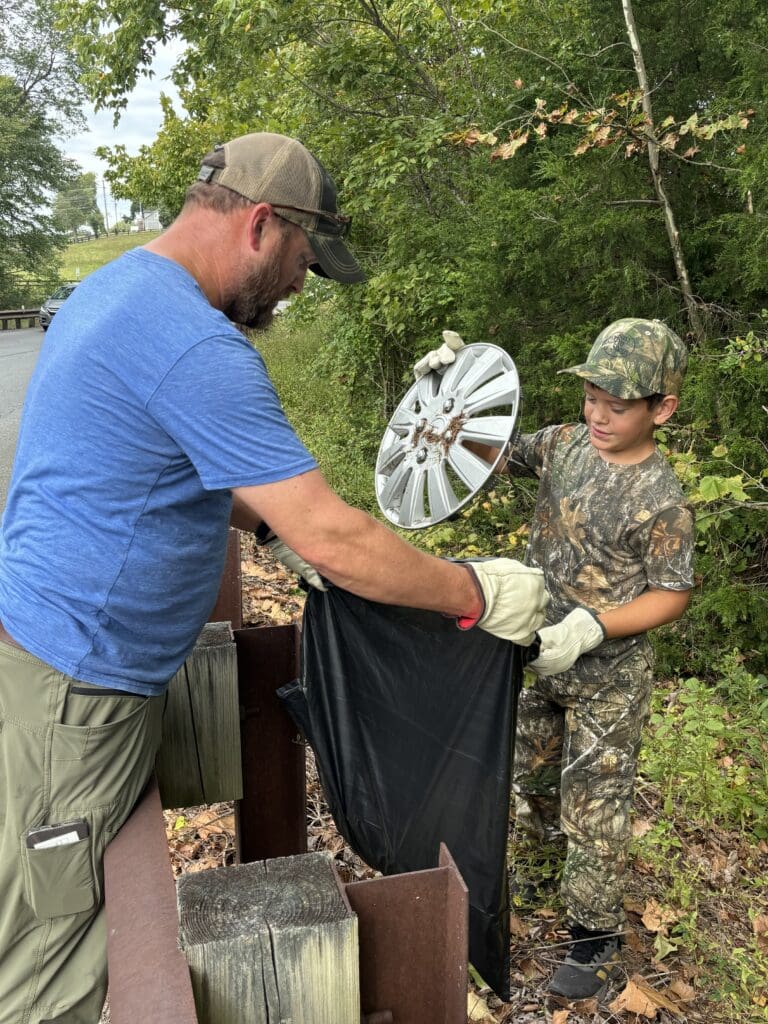

Volunteer groups spread out in multiple directions: some headed for parking lots, others made for bridge crossings, and still more focused on hunting areas. (One particular area at Phelps includes special hunting stands for disabled hunters.) My group, walking alongside the Rappahannock River next to the public boat launch, included a mother and father scouring the area for trash while their six-year-old daughter collected wildflowers. Charlie Mearkle, production manager for a custom home builder in Middleburg, attended the packout with his 10-year-old son. “Luke, I see something over there,” he said, pointing into some high grass. With the agility of a jackrabbit, Luke plunged in and out of brush piles, crawling over guardrails with alacrity and retrieved a hubcap. “Be careful, son,” advised the elder Mearkle to the younger. “That’s poison ivy over there, and if you get that on you, I’m going to hear about it from your mother when we get home.” Why were the Mearkles picking up trash this morning: “Well, it’s simply, really. We like to fish here, so I want to keep it clean. I brought Luke and his brother along because we need to pass on our traditions to our children. If we don’t teach our children to appreciate the outdoors and take care of it, who will?”

Avid angler Mike Leonard, who works for American Sport Fishing Association a national non-profit that advocates for the sport fishing industry and recreational anglers, feels much the same way. “My brother is planning on participating in the disabled hunt at the Hogue tract this fall so this is a chance for me to scout out the area and pick up trash at the same time.” Lenoard when on to say, “Today’s activity provides a great opportunity for me to spend some quality time with my kids and to demonstrate how we can give back to others in our own community.”

A car slowed as it approached our group, the driver rolling down his window. “Thanks so much,” shouted the driver as he passed us. “Really—thank you so much!” Our group smiled and waved in return. He was the first but hardly the last: Other drivers followed suit, honking their horns and waving in appreciation and thanks.

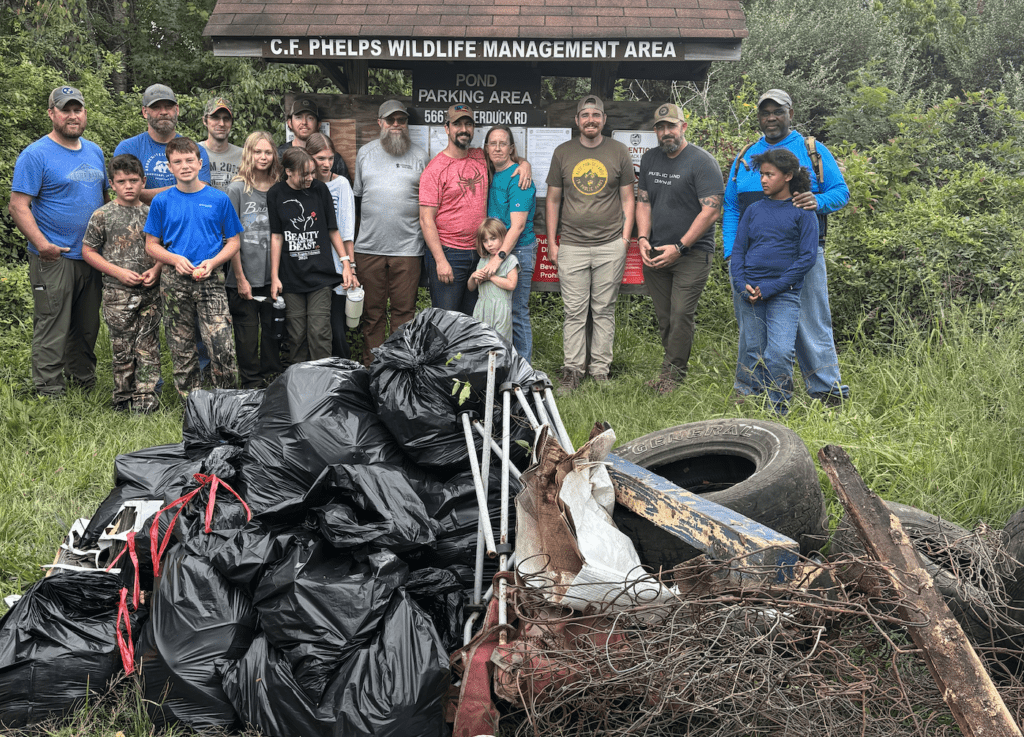

Back at Robinson’s truck a few hours later, the volunteers remained cheerful, though the site now looked like a miniature dump: More than 30 trash bags were piled high with plastic soda and water bottles, ubiquitous beer cans, discarded clothes, an extremely fragrant container of used cat litter, seven discarded tires, a box spring, and numerous old posts that someone had lazily thrown out in the woods.

After a group photo—taken alongside our spoils of war—Robinson, with military precision, filled his once-empty truck with the collected detritus. In went the tires, followed by the trash bags and posts. The box spring didn’t fit, so Robinson vowed to return the following day to pick it up. He thanked volunteers again, reminding them that this sort of work is central to the mission of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. The organization, focused on getting Americans outside to hunt and fish in public places, also has “a strong conservation ethic,” he said. After all, what good is it to advocate for outdoor sports if the outdoors has been spoiled? “I look forward to seeing you folks back here next year,” concluded Robinson, “when we’ll do this all over again.Beau Beasley is an award-winning outdoor writer who covers conservation, as well as public access issues. His latest book Healing Waters: Veterans’ Stories of Recovery in Their Own Words was recently released. You can purchase them from the author, your local shop or amazon.

Read the full article here