I have killed five bears above the black-bear class with a bow in the last six years and tackled two others that proved too much to handle that way and had to be stopped with a rifle. From those seven encounters, I’ve formed a rather firm opinion on a perennial question: What is the most dangerous game animal on the North American continent? I believe I know.

I took my first grizzly in the Devils Lake country of the Yukon in September, 1956, dropping him with one arrow from a 65-pound bow. I related that story in “Arrow for a Grizzly” (see OUTDOOR LIFE, October, 1957).

What happened, briefly, was that we spotted the bear half a mile away, mistook him for a big black, and my hunting partner, Dr. Judd Grindell, and I climbed off our horses and went after him. Because we thought he was a black we didn’t have the backing of a guide or rifle, and I even left my .44 Magnum Smith & Wesson, intended for use in emergencies, hanging on my saddle. When I caught up with the bear it was on the far side of a ridge digging for a marmot. I crept up until I was crouched behind a rock only 25 yards away. Then he looked my way and I discovered my mistake. The situation was one I had never intended to get into, and I realized the chance I was taking if I drove an arrow into him at that range. There was almost no chance, no matter where I placed it, that it would kill him before he could travel the 75 feet that separated us, and there was no gun behind me. Even Judd, also armed with a bow, was 150 yards away.

But I had come too far, hunted too hard, and wanted a grizzly too much to back down. I let fly and the arrow sank out of sight between the bear’s ribs. It sliced all the way through, cutting lungs, liver, and intestines, emerged and stuck in the hillside beyond.

He growled, bit at his side, swiveled around, and made two leaps my way, snarling and bawling. But before I could get off a second arrow he lost track of me or changed his mind, swerved, ran 80 yards, and fell dead. Three years later, in the fall of 1959, I killed my first brown bear, along the coast of Prince William Sound north of Cordova, Alaska. Medium size, he gave me no more trouble and even less of a scare than the grizzly. I laced an arrow into his lungs at 60 paces, he ran 50 to 60 yards away from me, went down, and stayed.

Then, in April of 1960, I tangled with my first polar bear on the ice off Point Barrow. That turned out to be a different kind of affair.

Bob Munger, a sporting-goods dealer from Charlotte, Michigan, a bowhunter and cameraman as well as a rifleman, and I flew up to Barrow that spring, hoping to collect two trophy-size white bears.

Flying over the ice fields of the Arctic Ocean 50 miles offshore, we spotted a good one following a pressure ridge across a big floe. George Thiele, my pilot-guide, landed on smooth ice nearby, and once we were safely down Bob and his pilot also landed. We decided I’d shoot the bear while Bob took pictures.

Thiele and I moved in, hidden by the ridge, with Munger behind us with two cameras. George was carrying a .300 Magnum as bear medicine if anything went wrong. We inched up within 17 yards of the bear. He was facing away from us and all we could see was his rump over the top of a block of ice. There was no way to work around for a shot at his rib section without great risk of spooking him.

I looked at George for instructions. “Shoot him in the hind end,” he urged. “He’ll turn to fight the arrow, and you get in a good one.”

Shooting a polar bear in the rump at 17 yards to make him turn around didn’t seem to me like the best procedure, but George knew a lot more about this business than I, so I did as I was told.

The bear turned all right, but the rest of it didn’t go according to plan. When I drove a four-bladed broad-head into his rear, he whipped around and came at us in one motion, bawling his rage. We hadn’t even realized that he knew we were there.

Thiele blasted a shot into his chest and it stopped but didn’t floor him. I got off a second arrow that cut through a foreleg, glanced off the bone, and stuck in his neck, not deep enough to do damage. He chewed and tore that arrow out in one second flat, and then started for us again.

Before he had made two jumps George slammed another 180-grain bullet into his chest, and again he stopped but didn’t go down. He was in shock now, however, and stood with blood gushing out of him until he fell over, just nine steps from us.

The whole thing left me in possession of a filled polar-bear license, a trophy I couldn’t claim as a bowhunter, and some brand-new ideas about ice-bear behavior.

Those three encounters, with the grizzly, the brown, and the white bear, so different in outcome, set me to wondering about the matter of dangerous big game and which North American animal is most likely to make trouble for a hunter. Now, four bears later, I still don’t claim to be sure of the answer, but I find myself leaning more and more to the opinion I formed that day on the ice.

Hunters who have shot most or all the big game of Canada, the United States, and Mexico may argue about which is the greatest trophy, but there is little disagreement among them on one point. The most touchy and danger-fraught characters an American hunter can go up against are the three big bears.

They’re all short-tempered and unpredictable, slow moving one minute, lightning and fury the next, with the brute strength to kill a man with one swipe of a paw and the vindictiveness to maul him as long as they can see him breathe. They have all done those things, and they rate at the top of every hunter’s list when he thinks of animals capable of retaliating.

That’s as far as agreement extends, however. Ask which one of the three is most likely to try to get even with whatever hurts him and you get varying opinions.

I strongly suspect that any general poll among sportsmen would give top place to the brown. He reaches tremendous size, has a hair-trigger temper, and has maimed or killed more men than any other animal Americans encounter — partly because he is hunted more frequently than either the grizzly or the polar. The tales of brown bear ferocity and attacks, provoked and unprovoked, are legion. Legends have grown up around this animal and he is feared more than any other carnivore in this part of the world.

But I’m not sure the choice of the brown for maximum vindictiveness would be right. More than one hunter who has taken all three bears would question it, I among them. I have more than a sneaking suspicion that the one that fears man least and is most ready to fight, once his anger is aroused, is the polar bear.

I’ll make one claim in defense of my ideas. I get well acquainted with the game I hunt. An animal is likely to do things at close quarters that it wouldn’t do at 200 to 300 yards, and if anybody has a chance to study the temper and behavior of game threatened or wounded at very short range it’s the hunter who uses a bow, as I do.

Despite the fact that I make several hunting trips each year, I have not hunted with a rifle in more than 25 years. I put my rifles away around 1935, when I went into the business of making archery tackle at Grayling, Michigan. Every trophy I have taken since — and the list includes deer, elk, antelope, moose, Dall and stone sheep, goats, caribou, black, brown, and grizzly bears, plus three kinds of African antelope — has been killed with a bow.

That means I have done almost all my shooting at 50 yards or less, the bulk of it at 15 to 30 yards, and I have had plenty of opportunity to observe animals in tight spots. It’s when you have your target in your lap and he knows you are there that you find out exactly what sort of critter he is. My opinion regarding the relative fierce-ness of the three big bears is based on situations of that kind, and all seven of my encounters tend to bear out the theory that the polar is the one surest to come for you if you give him cause. On the way home from the polar-bear hunt in 1960, Bob Munger and I stopped off at Kodiak and put in 10 days with Ed Bilderback, a Cordova outfitter and guide, on Kodiak Island and along the Alaska Peninsula looking for a good brown. The one I had killed the previous fall had turned out to be too small a trophy to satisfy me. You may remember my story of that spring hunt, “You Go, I Stay” (see OUTDOOR LIFE, March, 1961). We saw a big brown on the beach and I went after him, with Ed backing me with his .375 Magnum. We made the stalk through a patch of alders, came out on the beach 50 yards from the bear, and I went on alone, creeping to a spot behind a pile of driftwood 20 paces from him.

He turned broadside to me and I sent an arrow into his liver section the full length of the shaft. He let out a roar and spun around, biting at the arrow, giving me time for a second shot. That one hit him in a front leg and did no real damage, however, and then he came straight for me. Up to that time he hadn’t seen me, but when he was exactly five yards away and I was ready to blast him with my .44 Magnum sidearm, Ed yelled at me to hold my fire. The bear heard him and spotted me in the same instant.

He could have been on top of me in another jump or two, but for some reason he swerved and ran into the alders. He traveled 200 yards in all and was dead when we got to him. Why didn’t he finish what he started, when he had only 15 feet to come to do it? I still don’t know.

That made two browns and a grizzly I had taken without any real trouble, unless you call being scared half to death trouble, in marked contrast to what had happened with the one polar. A year from that fall I went to British Columbia for another grizzly, hunting on the Kispiox River out of Hazelton. I came across a good silvertip (he weighed around 500 pounds) fishing in a creek, got up to him until I was on the bank only 15 yards away, and whacked an arrow into him point-blank. But it hit a little too far back for a quick, clean kill.

He reared upright to fight the arrow and gave me time to get another on the string. I’m not sure whether he located me (that’s one advantage of bowhunting; you make very little commotion), but if so he did nothing about it. Instead, he dropped back on all fours and lit out for the opposite bank. Trying for a lung shot, I led him too much and the arrow punched a hole in his skull, slashed all the way through the brain, and lodged against heavy bone on the far side. He was dead on his feet but ran another 40 yards by reflex. My opinions about the behavior of grizzlies, browns, and polars in a showdown were growing stronger.

In the spring of 1962, I gathered some additional evidence of a very convincing nature. I went back to Point Barrow for another try at a polar bear with the bow, and again Bob Munger accompanied me. He had killed a good polar with rifle on the 1960 hunt and didn’t want another. He’d do only camera work this time.

Flying over the ice 20 to 30 miles offshore, we found one of the size I was looking for. George Thiele was my guide and pilot again, and he buzzed the bear to see what would happen. The animal wasn’t a bit afraid of the plane. As we slanted down on him he came raging toward us, mouth open, defiance written all over him.

He lined out across the ice and Thiele set the plane down a long way ahead of him. We picked a spot behind a jumble of ice blocks where we thought we could intercept him and hunkered down. It was a good place for everything except moving in a hurry. Snow had drifted in and was piled to our hips.

The bear came on at the rolling, shuffling walk that takes one of the big white brutes across as many as 25 or 30 miles of ice in a day and started past us only 25 paces off. Just before he reached our position he saw us.

I had an arrow on the string. Thiele was beside me with his .300 Magnum, Bob a few yards behind with two cameras. The bear didn’t even hesitate. He kept on at the same unhurried walk, turning his head to watch the three men crouched in the snow.

Hunters and arctic explorers have sometimes theorized that a polar bear attacks because, roaming remote offshore ice fields all his life, he has never encountered a man before, mistakes the human for a seal or some other food animal, and attacks out of hunger. In support of that belief, ice bears have been known to stalk and kill Eskimos watching at seal holes, and have also come boldly around frozen-in ships and camps searching for food. In the case of the bear we were after, the part about him having had no previous contact with men may well have been true. I can only conjecture about that. But hunger played no part in what he did, and he certainly didn’t think we were seals or anything else edible for he showed us only indifference until we made the first move. On the other hand, he was not afraid of us.

He changed course at a slight angle to veer off but didn’t quicken his pace or show any sign of alarm, just watched us over his shoulder as he walked. When he was directly opposite us I let my arrow go.

The range was short and I held where I wanted to hit, but he was moving faster than I realized. I knew instantly I had shot too far back. We had a wounded bear on our hands.

That can be a nasty situation, but he gave us no time to worry about it. The arrow was sticking out of his rump, but he didn’t pay any attention to it. He didn’t even bawl. He just changed ends and came for us like a thunderbolt.

George didn’t let him get far, but for a second or two his charge was as determined as anything I’ve ever seen, head low, coming to kill. Then Thiele’s 180-grain bullet smashed into his skull at less than 15 yards and he folded like a wet rag. His head went down under his forelegs, he rolled in a half somersault with his own momentum and slid to a stop. When we were sure he was dead, we walked around the hummock of ice and measured 10 steps from where we had crouched to where he lay.

He was a good bear, well up toward the record class, but for the second time in two years I was left with a filled license and a trophy I couldn’t claim because it had had to be stopped with a gun. And for the second time, I’d seen a demonstration of the lightning-quick rage of a wounded ice bear, their contempt of man, and their readiness to turn on him and kill or be killed in a no-quarter fight. “They’re white dynamite,” Thiele told me, “and timed with a damn short fuse.”

With that experience fresh in our minds, Munger and I left Barrow and flew to Cordova to join Ed Bilderback for another brown bear hunt.

We left Cordova at the end of April, aboard Ed’s boat, with Harley King along as second guicie and Dan Corea of Hawaii doing the cooking. We ran down the Kenai Peninsula and crossed over to Afognak Island, but spring was late, with the deepest snow in 20 years, and hunting was slow. Bob and I finally collected a black bear apiece with our bows, and then he put down a record-book brownie with his .375 Magnum. At the end of two weeks I had been within 30 yards of four bears, none real monsters but all good trophies. I’d even gotten within 15 feet of one. But something had gone wrong each time. Either the wind shifted or the bear spotted me and spooked before I could get a shot. Bob had to go home, and I was ready to call quits and leave with him. But the snow was going now and the hunting getting better, so, I decided to stay on and give it another whirl.

It took 10 days to make a contact, but it was worth it. We drew a blank on Afognak and finally crossed Shelikof Strait to the Alaska Peninsula, in the same area where I had taken my big brown in 1960.

There, running into a shallow, rocky bay rimmed by steep mountains, Bilderback, King, and I saw a good bear walk out of the alders onto the beach. We were in a skiff with an outboard.

Ed shut the motor off and started to row quietly for shore. If we could gain the cover of the alders without spooking the bear, we’d have an excellent chance for a stalk.

The brush came down to high-tide line all the way around the bay, but the tide was out now, leaving a narrow strip of rocky beach uncovered between the alders and the water’s edge. The bear was working among the rocks, pawing in the sand and kelp, stopping every few minutes to rest.

Harley kept binoculars on him, lifting a warning hand each time he looked our way, and Ed stopped rowing until the bear resumed feeding. He finally did something I’d never seen a brown do. He waded out into the sea, lay down and rolled over on his back with just his head and feet sticking out, and splashed like a kid in a pool.

We beached the skiff and slipped along the alders while he was dunking himself. A point jutted out into the sea about halfway to the bear, affording perfect cover for the stalk.

The wind was right and we wasted no time.

Ed and I went ahead, with Harley following about 25 yards behind. Now that Bob had gone home, Harley was our cameraman. He was carrying my 16 mm movie camera on a gunstock mount and, attached under it on the same stock, a 35 mm sequence camera that exposes 24 pictures with one winding. It’s triggered by a button on the gunstock, so the photographer can take movies and stills simultaneously.

I had only my bow. In addition to the two cameras and their mount, Harley had his .300 Magnum slung on one shoulder. Bilderback was carrying his favorite bear rifle, a sawed-off .375 Magnum. That’s a good gun for brownies, and it suits Ed perfectly. He figures that any shooting he has to do on a bear hunt will be at extremely close range, where a short barrel is as good as a long one.

We hadn’t gone more than 50 yards from the skiff when the bear’s blond ears came into sight over the point. He had left his bath and was walking into our laps. My first thought was that he was very wide between the ears and must be quite a bear. He was.

Just ahead of us was a rock about four feet square, hardly big enough to hide two men but better than nothing. We went for it on our hands and knees, motioning Harley to squat where he was and stay put. He was far enough back that we counted on the bear not noticing him until it was too late.

The beach was open save for the big rock. We knelt behind it, I with an arrow ready and Ed clutching his rifle. The bear came into sight, approaching at a walk, and we pulled our heads down between our shoulders like turtles. Unless he charged course, he’d pass between us and the sea, and the wind would be blowing from him to us. The minute or so it takes for an animal of that size to walk up within bow range is packed with suspense and thrills, and questions race through the mind like fleet shadows.

Would this big fellow keep coming or would he spot us and gallop off? Two weeks before, hidden at the edge of a thicket on Afognak Island, I started a slow careful draw on a bear at 17 yards. Out of the corner of one eye he saw the first movement I made and was off in a flash, bounding over big rocks like a huge rubber ball. He put 40 yards between us before I could release my arrow, and I missed. Would this one behave that same way? Or when he saw me would he stand and stare in puzzlement?

He did neither. He lumbered on, arrogant and unconcerned. He was 25 feet away and still coming — and then he saw us.

He stopped and swung to look us over. His head lifted, swinging from side to side in typical brown-bear fashion, and his muzzle wrinkled as he tested the wind. But it told him nothing, and Ed and I stayed as motionless as two driftwood stumps. We held our breaths and waited. Finally, satisfied, he turned broadside and started to walk past us.

The 65-pound bow came back to full draw, and the bear did not even glance our way at the movement. I decided to put the broadhead through his ribs, close to the shoulder. There is no better shot for a quick, clean kill. I held just back of a foreleg and the arrow sank to the feathers. The range was only 20 feet.

I’m convinced the bear knew what had hurt him and where we were, but he made no attempt to fight back. He let go a hair-raising roar and streaked down the beach, the way he was headed. I ducked back to give Ed room to swing his rifle to cover King.

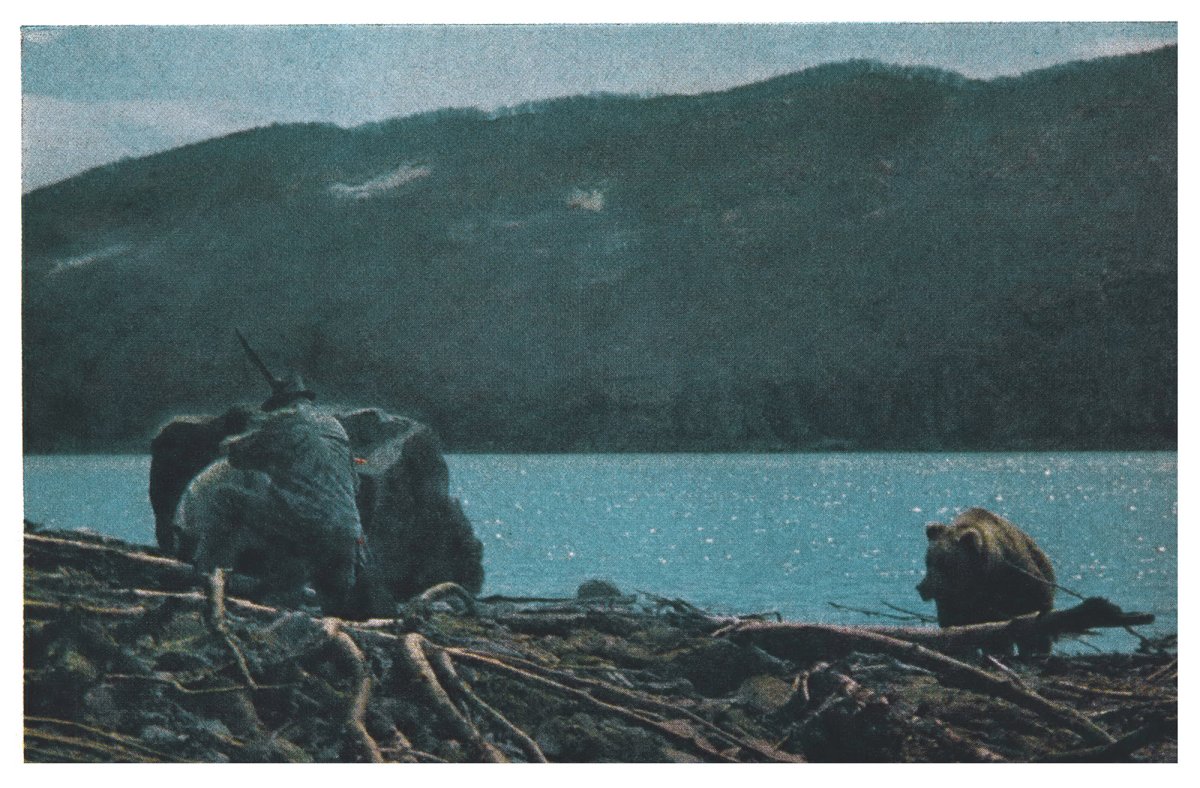

The bear still had Harley to reckon with, or rather Harley had to reckon with him. The beach was no more than 20 feet wide at that point, and Harley was squatted in the middle of it with the cameras going. The bear galloped straight for him, and if he hadn’t moved he’d have been run down. He stood his ground until the brownie more than filled the finder, then dived for the alders. It wasn’t funny at the time, but we had a good laugh about it later. The bear went past him 10 feet away without even glancing aside.

We turned up the beach and tried to climb into alders but couldn’t make it. He fell and rolled out of the brush, and in less than a minute after the arrow knifed in he lay dead almost beside our skiff. The four-bladed arrowhead had nicked a rib, sliced through a lung, cut off a big artery near the liver, passed through the diaphragm, and through the skin near the back ribs on the opposite side.

We managed, with considerable difficulty, to roll him into the skiff. From there we winched him aboard Ed’s boat for skinning and weighing. He tipped the scales at 810 pounds, the pelt squared nine feet, and the green skull scored 27 inches, an inch under that of the brown I had taken in 1960. That one went into the records as the biggest ever killed with an arrow.

This brownie had run off without a fight, at far closer range and under as great provocation as the polar I had wounded a month earlier, the one Thiele had to put down with his .300. That one had come for us without a split second’s hesitation. This bruiser, close enough to have been on us before Ed’s .375 could have stopped him, had not even turned our way. Why? I have no answer.

But I’ll go back to what I said before. I’m convinced that the polar bear is just naturally the one to watch out for. It’s true, of course, that one swallow does not make a summer, and by the same token maybe seven close encounters with brown, grizzly, and white bears do not qualify me as an expert on their behavior. But at least those seven brushes entitle me to an opinion.

I realize there are exceptions to every rule, and even if I’m right in rating the ice bear at the top as a dangerous trophy I know there’ll be many future occasions when a grizzly or brown will go out of his way to disprove my theory.

We had a spine-chilling example of that on our British Columbia hunt in 1961, the fall I killed my second grizzly. On two occasions we had seen a sow silvertip with three cubs in tow and had stalked her for pictures, getting up within 25 yards. Each time she had winded us and run off.

A couple of days after we saw the bears, Bob Munger and Dick Mauch, another member of our party, made a fishing trip to a small lake with their guide Bill Love. When they left the lake they started up over a steep, rocky point on the way to camp. Bob and Dick were carrying their rods and bows. Bill had a light pack and a .270 Winchester Model 70 slung on his back. Bill was in the lead, Bob behind him, and Dick was bringing up the rear. They were no more than away from the shore when they heard a low snarl behind them. Then brush broke and they saw the sow grizzly, clawing her way up the moss-covered rocks as fast as she could, growling and raging.

The poor footing slowed her down and that was all that saved them. Bill barely had time to shuck the pack and whip his rifle up. The 150-grain soft-point dropped her just 15 feet away.

There were only two of the cubs left. She had lost one in some fashion, and maybe because she had smelled us in the area a couple of times she blamed us for its disappearance.

Whatever her reasons, she picked the fight without being molested or provoked in any way. That’s grizzly behavior for you, under the right circumstances. Other silvertips will do the same thing again, and other browns will stand and fight instead of running away as my three have done.

Read Next: Watch: Footage of Fred Bear Hunting His First Grizzly, with the Legendary Razorhead Broadhead

But I still lean to the belief that the one most likely to come for you if he gets the chance is the big, fearless bear of the ice fields, maybe for no better reason than that you will be the first man he has ever encountered and he has no reason to respect you.

One of these days I’ll collect a polar-bear pelt with no bullet holes in it, one I can count on my list of bowhunting trophies. When I do that I’ll consider that I have killed the most dangerous animal a hunter can tangle with on this continent.

Read the full article here